Once Undocumented, a New American Citizen Prepares for College

With Spanish Translation

November 26, 2018

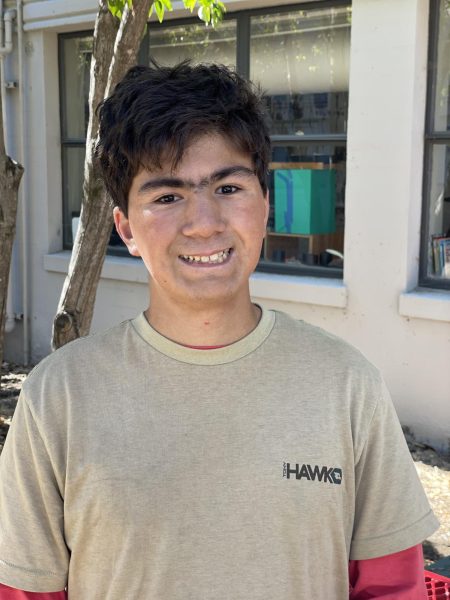

The lights dim as Jose Antonio Vargas walks to the stage. Fatima Ayala waits for him to sit and she claps as he pronounces his name. She laughs when he explains what people think reverse racism is. She nods as he explains that America was built by immigrants. She snaps when he says “people of color” and “undocumented citizens.”

An hour later, it’s time for questions. The room becomes rows of raised hands. We are seated with thirty students of color but none of their questions get answered. After he finishes signing books, he walks to our side of the room and lets us ask questions. Ayala’s hand shoots up. Her voice is shaky. “Like you, I lived away from my mother for most of my life and I recently reunited with her. I always knew I had a mother but I couldn’t connect a face with that word until five years ago.” She is vulnerable, but she continues. “If or when you reunite with your mother, what is the first thing you would like to tell her?”

The room is silent as he blinks away his forming tears. He says, “I would thank her”.

She walks out of the meet and greet with a gentle smile and a pin that says #WhyImHere on her shirt.

Ayala grew up in El Salvador. When she just had learned how to walk, her mother made the journey to the US. The daily Skype calls from her mother did not reinforce the bond they had lost many years before.

When she was four, Ayala was accepted to an institute that taught young children how to speak English. Later when she started middle school, she took an English class so she practiced the language of opportunities everyday.

Still, her Spanish-speaking country was not the right place to practice English. Hours of studying a language she would almost never have to use was pointless to her. Her mother reassured her that one day she would get to use it.

“I was twelve years old,” she says, “My mother called and told us she bought us tickets to the US under a temporary residency. We left that day.”

Ayala was not an unaccompanied minor. She did not have to make the difficult journey to the US like most of her family before her did. Still, she was an immigrant entering a country where even her mother was a stranger.

When she arrived in the U.S, she began seventh grade. “I hung out with the Spanish speaking kids because I didn’t feel comfortable speaking English”.

“When I came to this country I was determined to learn English and that meant I had to end all my friendships with the students that only spoke Spanish.”

Ayala distanced herself from the only people who welcomed her on the first day of school. “I had to do it. It was the only way I would be able to learn the language and use it to succeed.”

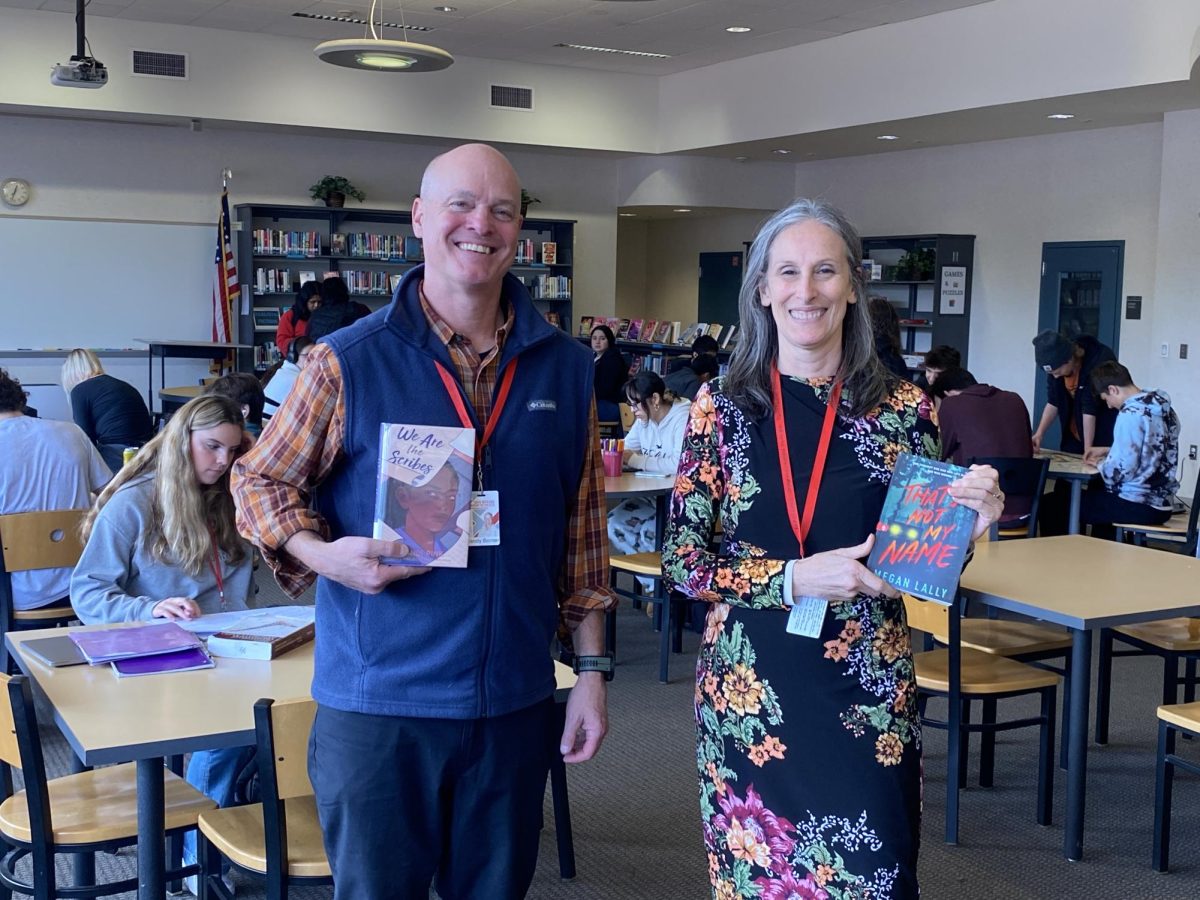

After deciding college was the only way to avoid becoming yet another member of the College of Marin statistic, Ayala applied to the rigorous college access program, Next Generation Scholars. We met at this program sophomore year.

The summer classes in public speaking and physiology offered by this program gave Ayala the opportunity to create a class that would help students bond and communicate with others, just as she did when she arrived from her home country. The students learned how to approach different socially intimidating situations and she learned that her voice is valuable.

In school, she now dominates the conversation in the classroom acknowledging that her fading accent will be heard by all as she speaks in a once-foreign tongue.

Ayala was able to build close relationships with her teachers because she was able to excel in classes she would not have understood if she never learned English. She now has secured her spot on their list of students for whom they’ll be writing letters of recommendation to. She has taken classes at Next Generation Scholars which have inspired her to study behavioral economics.

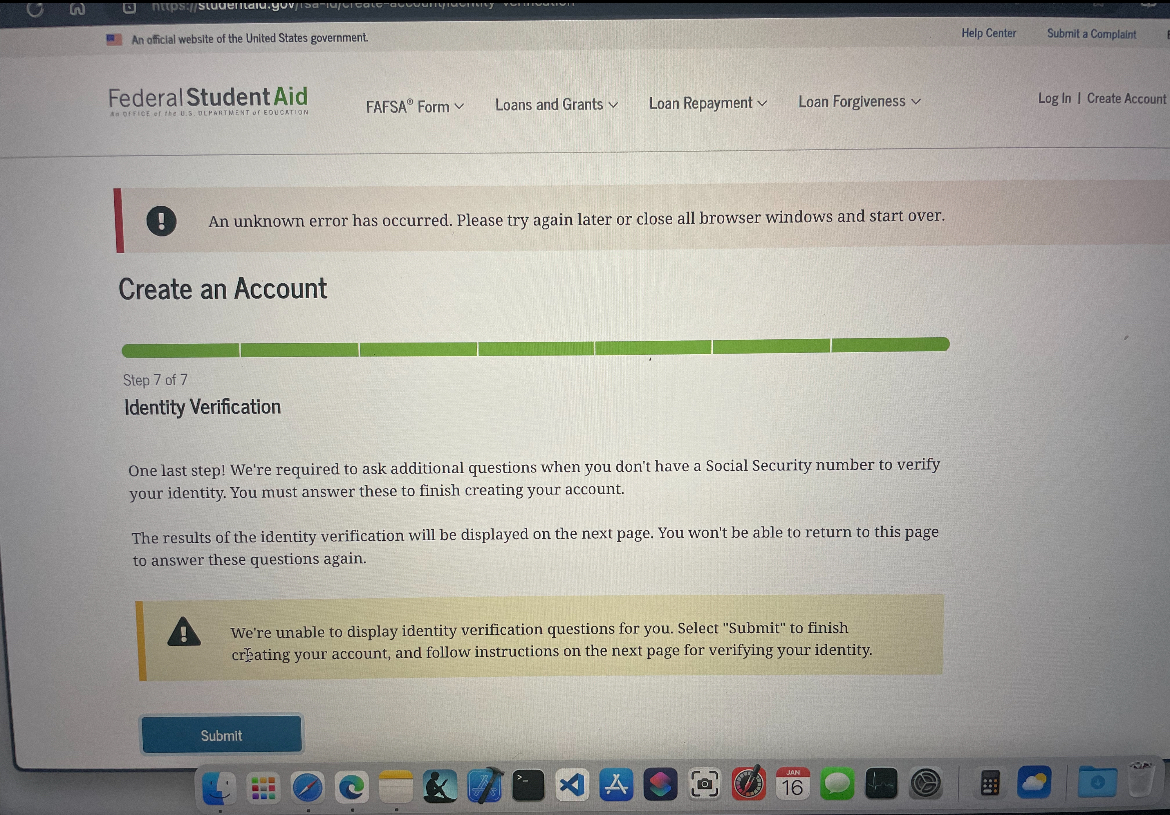

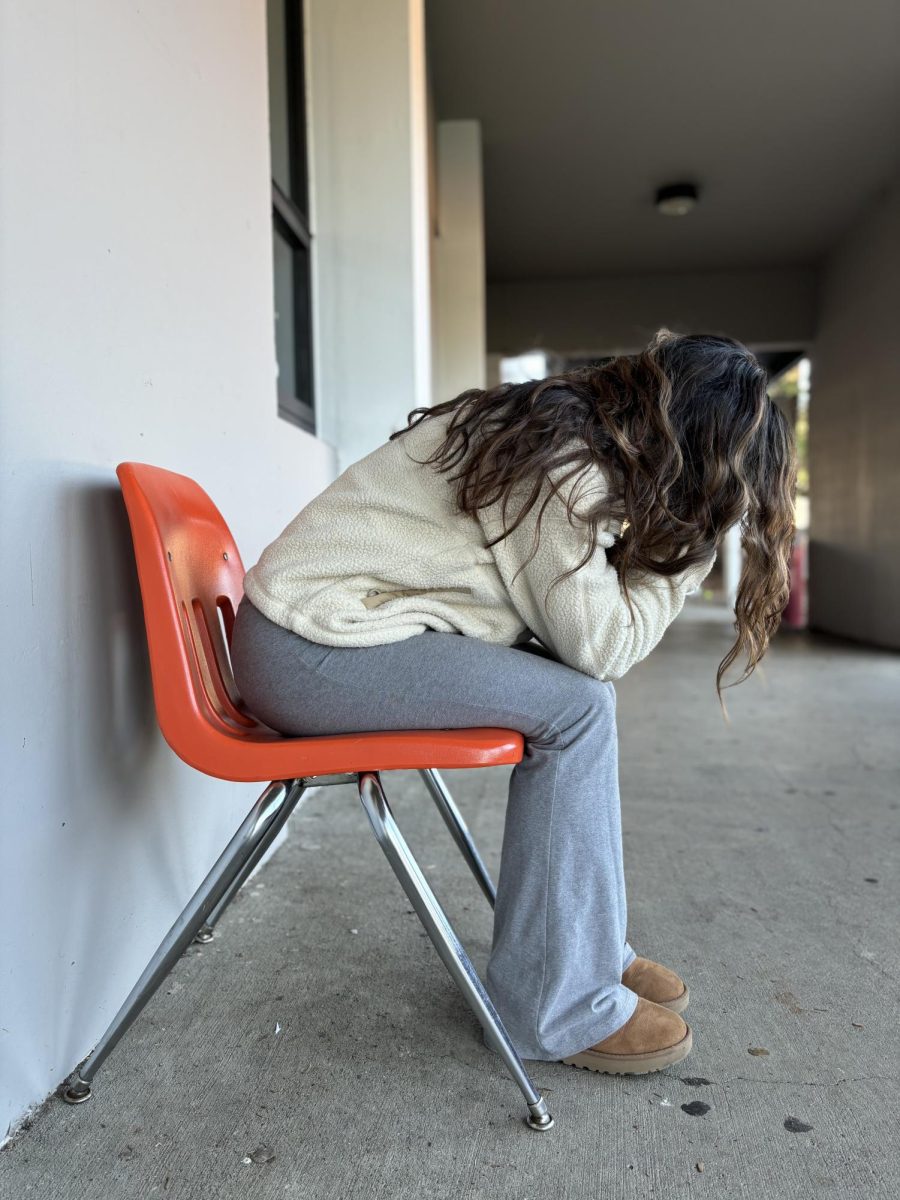

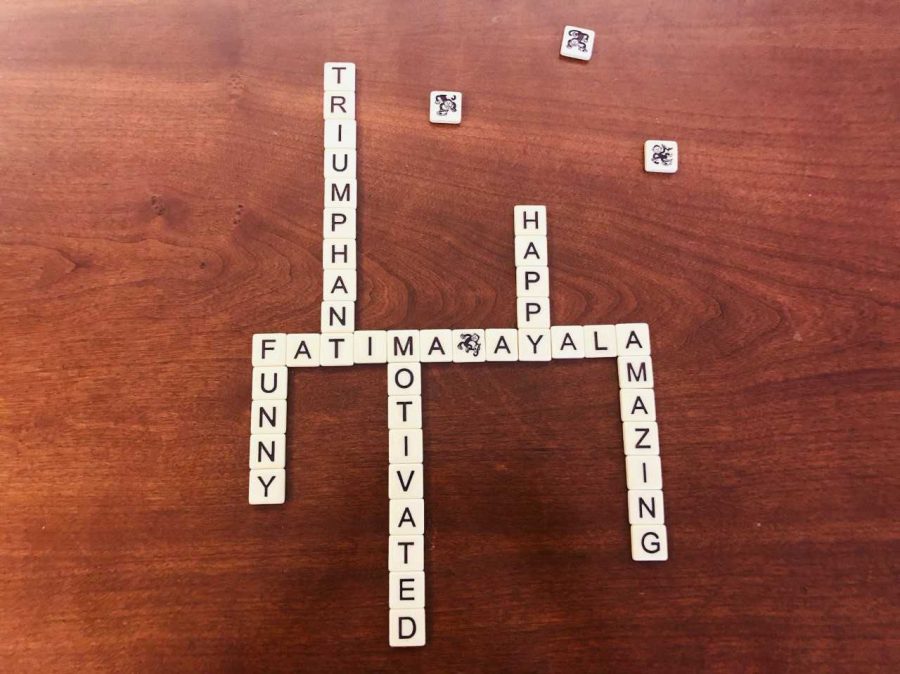

Ayala is not the first, and she won’t be the last, first generation college student. But, she no longer worries that her former immigrant status will affect her ability to obtain this label. Her low income background makes it crucial for her to complete financial aid applications that put her residency into question. She distracts herself with a game of Bananagrams as she waits for her mother to send her a picture of her social security number.

“We should play a round only using Spanish words,” she suggests.

Just before we surrendered to her vast Spanish vocabulary, she had her social security number and was ready to apply for financial aid and then, to college.

Ayala became a citizen last year when her mother passed her citizenship test. “I am a minor so when my mom got her citizenship, I did too.”

The cameras are out. Everyone is recording. We gather around her laptop. The submit button is highlighted in red. Her arrow is slowly moving towards it. On Halloween, Fatima submitted her early decision application to Wellesley College, an all women’s liberal arts school in Massachusetts.

One out of ten schools submitted. One more than she would have been able to submit to five years ago.

Spanish Translation:

Las luces se apagan cuando José Antonio Vargas camina hacia el escenario. Fátima Ayala espera que él se siente y ella aplaude cuando él pronuncia su nombre. Ella se ríe cuando él explica lo que la gente piensa que es el racismo inverso. Ella asiente mientras él explica que América fue construida por inmigrantes. Ella chasquea cuando él dice “gente de color” y “ciudadanos indocumentados”.

Una hora más tarde, es hora de hacer preguntas. La sala se convierte en hileras de manos levantadas. Estamos sentados con treinta estudiantes de color, pero ninguna de sus preguntas es contestada. Después de que termina de firmar libros, camina hacia nuestro lado de la sala y nos permite hacer preguntas. La mano de Ayala se levanta. Su voz esta temblorosa. “Al igual que tú, viví lejos de mi madre la mayor parte de mi vida y recientemente me reuní con ella. Siempre supe que tenía una madre, pero no podía conectar una cara con esa palabra sino hasta hace cinco años “. Es vulnerable, pero continúa. “Si así fuera o cuando te reúnas con tu madre, ¿qué es lo primero que te gustaría decirle?”

El salón se pone en silencio mientras él parpadea para alejar sus lágrimas formándose. Él dice: “Le agradecería a ella”.

Ella sale de la reunión y saluda con una sonrisa suave y un botón en su camisa que dice #PorqueEstoyAquí.

Ayala creció en El Salvador. Cuando acababa de aprender a caminar, su madre hizo el viaje a los Estados Unidos. Las llamadas diarias de su madre por Skype no reforzaron el vínculo que habían perdido hace muchos años.

Cuando ella tenía cuatro años, Ayala fue aceptada en un instituto que enseñaba a los niños pequeños a hablar inglés. Más tarde, cuando comenzó la escuela secundaria, tomó una clase de inglés, por lo que practicó el lenguaje de las oportunidades todos los días.

Aún así, su país de habla hispana no era el lugar adecuado para practicar inglés. Las horas de estudio de un idioma que casi nunca tendría que usar no tenían sentido para ella. Su madre le aseguró que un día podría usarlo.

“Tenía doce años”, ella dice, “mi madre llamó y nos dijo que nos compró boletos para los Estados Unidos bajo una residencia temporal. Nos fuimos ese día “.

Ayala como era menor tenía compañía. Ella no tuvo que hacer el difícil viaje a los Estados Unidos como la mayoría de su familia antes que ella. Aun así, ella era una inmigrante que ingresaba a un país donde incluso su madre era una extraña.

Cuando llegó a los Estados Unidos, comenzó el séptimo grado. “Me juntaba con los niños que hablaban español porque no me sentía cómoda hablando inglés”.

“Cuando vine a este país, estaba decidida a aprender inglés y eso significaba que tenía que terminar todas mis amistades con los estudiantes que solo hablaban español”.

Ayala se distanció de las únicas personas que la recibieron el primer día de clases. “Tuve que hacerlo. Era la única forma en que podría aprender el idioma y utilizarlo para tener éxito “.

Después de decidir que la universidad era la única manera de evitar convertirse en un miembro más de la estadística del College of Marin, Ayala se aplicó al riguroso programa de acceso a la universidad, Next Generation Scholars. Nos conocimos en este programa en el décimo grado de Sophomores.

Las clases de verano para hablar en público y fisiología ofrecidas por este programa le dieron a Ayala la oportunidad de crear una clase que ayudaría a los estudiantes a vincularse y comunicarse con otros, tal como lo hizo cuando llegó de su país de origen. Los estudiantes aprendieron cómo abordar diferentes situaciones de intimidación social y ella aprendió que su voz es valiosa.

En la escuela, ahora domina la conversación en el salón, reconociendo que con su acento desvanecido, su voz será escuchada por todos mientras habla en lo que antes era una lengua extranjera.

Ayala pudo establecer relaciones cercanas con sus maestros porque pudo sobresalir en las clases que no habría entendido si nunca hubiera aprendido inglés. Ahora ha asegurado su lugar en su lista de estudiantes para los cuales escribirán cartas de recomendación. Ella ha tomado clases en Next Generation Scholars que la han inspirado a estudiar conducta económica.

Ayala no es la primera, y no será la última estudiante universitaria de primera generación. Pero, ya no le preocupa que su estatus anterior de inmigrante afecte su capacidad para obtener esta etiqueta. Sus antecedentes de bajos ingresos hacen que sea crucial para ella completar las solicitudes de ayuda financiera que ponen en duda su residencia. Se entretiene con un juego de Bananagrams mientras espera a que su mamá le envíe una fotografía de su número de seguro social.

“Deberíamos de jugar una ronda usando solo palabras en español”, sugiere.

Justo antes de rendirnos a su vasto vocabulario en español, obtuvo su número de seguro social y estaba lista para solicitar ayuda financiera y luego a la universidad.

Ayala se convirtió en ciudadana el año pasado cuando su mamá pasó su examen de ciudadanía. “Soy menor de edad, así que cuando mi madre obtuvo su ciudadanía, yo también lo hice”.

Las cámaras están fuera. Todo el mundo está grabando. Nos reunimos alrededor de su computadora. El botón de enviar está resaltado en rojo. Su flecha se está moviendo lentamente hacia ella. En Halloween, Fátima presentó su solicitud de decisión temprana a Wellesley College, una escuela de artes liberales para mujeres en Massachusetts.

Una de cada diez escuelas solicitadas. Una más de lo que ella hubiera podido solicitar hace cinco años.

Tom Kernan • Dec 19, 2018 at 4:56 pm

Excellent article, Jocelyn. Fatima was one of my students at DMS. She was a wonderful student and person then, and it sounds like she has continued that at SRHS, which doesn’t surprise me. I’m very proud of all that she has accomplished.

Simmons • Dec 10, 2018 at 10:48 am

I really like this story!