Unexpected Reunions and The Journey North from Guatemala to San Rafael

June 3, 2022

With a yellow folder filled with documents in hand, Leyven Lopez readied himself to board a plane. The plane would bring hope for a different life, in the land of the American dream. Little did he know, in a short few months, he would reunite with someone he didn’t expect to see again.

Like the rest of the farmers in Colomba, a town in Guatemala, Leyven’s family regarded the mountain and its lush soil as a divine gift. He was brought up to work the land, learning to harvest coffee beans. He worked on several plantations owned by wealthy landowners.

From around the age of eight, he rose with the sun. The smell of frigid air filled his lungs. Then, he walked to the fields with his mother, where he handpicked hundreds of matured coffee beans. The citric smell settled on his fingertips for days. He filled sacs of the precious bean weighed in quintales (a quintal is 100 pounds). His hard work amounted to 100 quetzales per sack, around 12.97 US dollars.

Leyven’s father left him when he was six months old. He planned to make extra money up north to send back home. It would be hard at first, but with time he knew he could work his way up that ladder of the American Dream.

His father hired a coyote, a guide who would smuggle him through the dangerous route up north into the United States. To pay the coyote he used almost all of the family’s savings. He realized that he was accountable for the family’s faith and that he needed to send money home as soon as possible. He expected to be in the United States after a couple of weeks, and after a couple more he’d have a job and the ability to send money home.

Leyven had lost his father. His sadness at his loss was laced with resentment. Who knew if he would ever see him again.

Guatemala is home to 16.8 million people; around 1.4 million Guatemalans resided in the U.S in 2017.

Between 1960 and 1996, over 400,000 Guatemalans fled to the United States, Mexico, and Canada due to the civil war. Migrants included student and union leaders, intellectuals, and others displaced by political oppression. Migration figures rose with the intensification of violence from the late ’70s through the ’80s.

Leyven idealized the US just as many others had: a place with jobs, more stuff, and opportunities. An old phrase spread saying that “you could sweep dollars off the ground in el norte.”

Adults, children, and occasionally entire families left Guatemala on a regular basis. Leyven daydreamed about it more after his buddies left. He imagined where people he knew had ended up.

Leyven imagined the life his father had, nice clothes, a car.

In the United States, we consider a family and every individual who belongs to it to be poor if the family’s total income is less than the threshold. For a family of five people: two children, one mother, one father, one grandmother the family would be considered in poverty if their threshold is under $31,661. According to a study done by the Public Policy Institute of California, around 13.3% of Californians lacked enough resources-about $24,900 per year for a family of four- in 2017.

According to the most recent data for Guatemala, about 49% of the population are poor or live below the upper-middle poverty line which is about 5.5 dollars a day, $2,008 a year, in 2014.

People wanted-they needed to get out to stay alive.

Leyven was no stranger to the brutal behavior of gangs and corruption.

“Where do you think you are going?” one of the young men asked, shoving Leyven, making him stumble back a couple of steps. Leyven, thirteen, was walking back from school when a group of older kids stopped him. Five or so guys sporting baggy clothes and tattoos stood by the roadside. They were part of the local gang that terrorized Colomba, a gang that was showing up more and more around town.

Leyven, usually outspoken, was scared silent from the sight of these men. His gaze lowered, but he could feel the men staring down at him.

“I asked you where you are going!” the man shouted. At that, Leyven took off running into the woods.

When the shouts sounded far enough away, he lay on the ground. He stayed there for what felt like hours until he was sure the men were gone.

Events like this were common in Guatemala.

One evening, Leyven went into his room and called his father. “Dad,” he said. “I’ve made up my mind. I want to go north.”

His father was quiet for a moment. After giving it some thought he said yes.

Horror stories about the trip were told daily by neighbors. Stories of children being raped in the desert, children dying of thirst, children run over by trains.

Such is the story of Esdras Diaz, an SRHS junior, who had to endure being kidnapped by the Mexican drug cartel.

“I saw a pregnant woman get beat with a rifle because she wouldn’t stop screaming,” said Esdras. His head turned downward as he reminisced.

After crossing the Guatemala-Mexico border, Esdrass’ bus was stopped by a group of masked armed men. He and his group were pushed, pulled, and shoved off the vehicle, pickpocketed, and threatened. Then they were transported to what Esdras recalls as a small storage depot in the middle of nowhere. For 2 weeks Esdras was kept in the small room. When the criminals finished calling the hostages’ families, asking for ransom, the group was released. Esdras managed to walk from the depot to a nearby town and made a call to his father with the spare change he had left; he didn’t say much about the incident. Just that he needed some money for food and a new phone. He had no other choice but to continue the journey alone.

To avoid events like these, people hire coyotes. The average rate for a coyote (smuggler) is around 7,000-10,000 dollars. There are some stories of people who have traveled on their own, with no coyote, and just enough cash for food, bus fare, and the occasional bribe. But, Leyven barely ever left his hometown, let alone Guatemala. Like his father, Leyven needed a guide. After paying the large sum of money Leyven was instructed to meet a stranger early in the morning. He would then drive him to the Guatemalan-Mexican border, the drop-off area was a small town called Ciudad Hidalgo, located in Chiapas, on the Mexican side of the border. He would then hop on a bus and ride through the Mexican Altiplano to the US border.

The views outside the bus window changed from greenery to arid desert.

Finally, he was there. The nervous feelings of being an outlaw enhance the dangerous perception of the South Texas desert: the whistling wind, scorpions shifting around brushes, the deep shrieks of a low flying hawk. Border patrol trucks crisscross one other like wolves. And in the middle, is the famous river, the Rio Grande, the original liquid border between the US and Mexico.

Trump’s motto to “build a wall” along the US-Mexico border was a scheme. The desert border wall already reaches about 650 miles on the two thousand-mile frontier. It’s not just one lengthy wall, but a slew of them that vanish abruptly against the backdrop of desert and ranches.

After the Rio Grande and the physical border wall, the next blockade migrants face is the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agents.

And then, within a hundred miles of the border are the checkpoints. Wearing bulletproof vests, sporting their leaf green uniform, black boots, and reflective sunglasses, holding tight to the leashes of dogs that sniff drugs or bodies, border patrol agents guard the checkpoints.

Leyven needed to reach one of these checkpoints.

With a simple order, Leyven’s journey through the desert started. “Start walking north,” a young man said, pointing towards the direction they ought to take. It was dark, Leyven wasn’t sure if it was approaching midnight or sunrise. The air was dusty and the cold was harsh. No one in his group knew exactly where they were heading or how far they needed to go.

After some hours of walking the stars in the sky shone bright, the dusty air had settled and an unnerving silence settled all through the valley. A light vibration could be felt through the sand. It took a couple of minutes for the guides to understand what was going on.

“Get down,” came the command.

The people in the group froze. Following the order, Leyven got down, his heart pumped and he felt a cold sweat coming out of his forehead. As the vibrations got stronger, people took to running as fast as possible. Not knowing where to move, but being afraid of being hounded out, Leyven took to running too. Leyven and a small group of people that managed to stay close made it to the checkpoint early at dawn.

“I am looking for my dad,” said Leyven, as the border patrol officials checked him for lesions and interrogated him.

Children arriving on the US-Mexico border alone are detained by border protection agents. They are formally classified as “unaccompanied alien children” if they are under 18 years of age. By law, within 72 hours, all unaccompanied migrant children must be transferred to the federal Office of Refugee Resettlement. Once children are transferred to the refugee agency, they initially are placed in a shelter or detention center. Any other unaccompanied child was sent to a hielera.

The official limbo zone of the US immigration system, the hielera, or icebox, is a cold, windowless room, packed with 20-30 other young men and boys. These rooms only have one toilet, and no beds or mattresses.

“Immigration gives out juice boxes and cookies every so often, they don’t feed you much,” said Leyven when asked to talk about his experience.

The punishing environment is an intentional tactic utilized by immigration advocates to break the spirits of immigrants, forcing them to opt for voluntary departure. After some time Leyven was taken from the hielera and interviewed by an immigration officer. He asked if there was anyone in the US they could call.

Levyen’s father picked up the phone a few rings later. “Hello?” he asked suspiciously.

“It’s Leyven, immigration has me,” said Leyven. No reply.

“Hello?” asked Leyven.

“Seriously? How are you?”

“I’m okay,” said Leyven.

The officer took the phone, asked Leyven’s father a series of questions, and wrote down his information. After making it through the icebox, Leyven was sent to a Refugee Agency, where he was placed in a shelter. There, he was given a new change of clothes and he was placed in isolation for three days as a precautionary measure.

“Nothing out of normal happened then, I got vaccinated and I was given a book once in a while so I could spend my time, I did have to be alone in the room though,” said Leyven.

When he was finally released from isolation, Leyven was put in a room with two lines of bunk beds. The staff woke him up early to take showers and do chores. Rooms were kept orderly. He played soccer with the other boys.

He stayed for a couple of weeks there. A social worker described what would happen to him after. She informed him that he had entered the country illegally and was still in danger of being deported. This would not happen until he had the opportunity to speak with a judge. She went on to say that his father had volunteered to look after him in the United States so he could stay. However, he would still have to face a jury and fight his plea.

His father bought a plane ticket to Oakland International Airport a few days later. Meeting his father was a very emotional moment for Leyven. Although he remembers the moment as being somewhat awkward, he shed tears of joy after almost two decades of finally getting the chance to see his father again. Resetting his entire life, in what seemed like a completely new world, was tough for Leyven. Being amidst a global pandemic only added onto the difficulty he was facing. Memories of his old home, Colomba, flooded Leyven’s mind.

Colomba, a tangle of greenery, with pine cones overhead and tall, shivering rows of pine trees, flourishing palm trees, pink flowering cacao, and Pacaya canopies. Colomba, which is around 150 miles from Guatemala City and has a population of fewer than 50,000 people, sprawls up and down the slopes of a mountain.

The homes along the road are simple yet warm, made of concrete, and painted in a variety of gentle colors. The surrounding hills and farmlands are scattered with less fortunate homes. Cattle use the road just as much as people. When the harvest comes, bean pods and maize kernels are laid out to dry, creating beautiful tapestries.

The road crests the hill and dips downward, and that’s where Leyven’s old home and a house belonging to his former neighbor, Frisly Santos, sit.

Frisly and Leyven spent a great deal of time together. Playing soccer with the other neighbors or swimming in the local river, challenging its mighty waters. They grew close and created a strong friendship. Frisly worked in construction with his father. He aided in miscellaneous jobs which included painting, different electrical and plumbing installations, and brickwork. Just like Leyven, Frisly got up with the sun and supported his family with work, then went to school for the afternoon session. Both their days were often long and without rest. From a young age, they saw the hardships they were born into. From a young age, they understood they had to search for other options.

Like Leyven, Frisly embarked on the journey north in search of a better life. He crossed the US-Mexico border along with his mother around 4 months after Leyven. But, instead of seeking refuge in California immediately, the pair settled in Georgia, living with one of Frisly’s aunts.

For reasons unknown to Frisly, his mother decided it was time to move out after a couple of months living with his aunt. The city they ended up choosing as a home was San Rafael, CA.

Unknowingly, under insurmountable odds, the two best friends ended up in the exact same city.

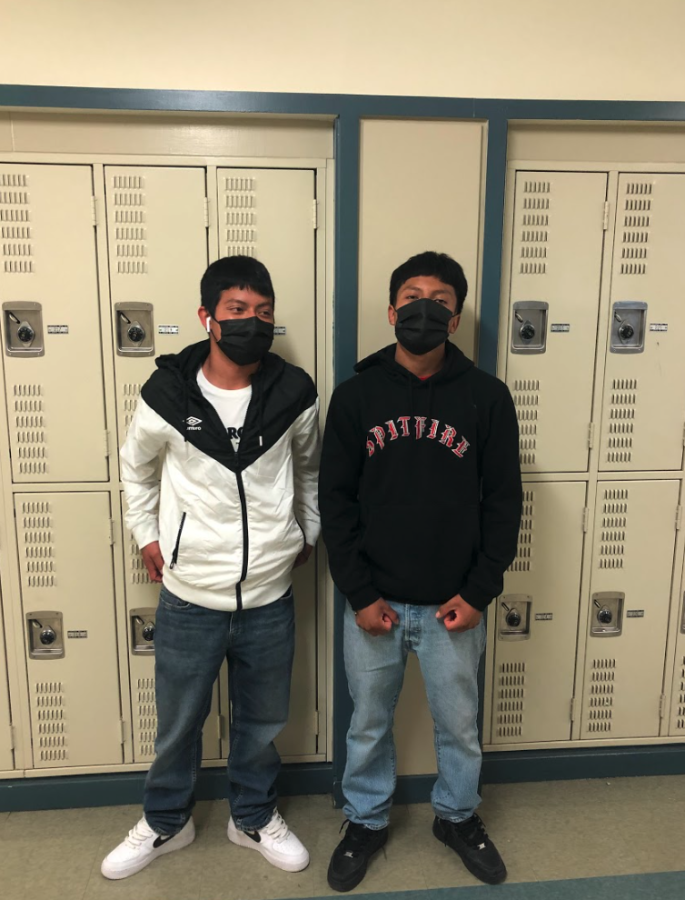

Leyven and Frisly reunited in the halls of San Rafael High School early one morning. Both of them were surprised when they saw each other again.

“Is that really you Frisly?” said Leyven.

“Oh damn, nice to see you again,” Frisly replied.

They were inseparable once more.

San Rafael serves as a gateway for immigrant families to start a new life, build a new home, and connect with a new community. According to the U.S. Bureau, around 16.3% of the population in Marin is Hispanic or Latino making it the second-largest ethnic group in the county. Close to half the unaccompanied minors coming to the United States were from Guatemala. A 2021 Marin Independent Journal story captured the impact of this immigration surge on the San Rafael community.

Under the heat of the blazing California sun, the two friends now share new experiences together. The isolated feeling they first experienced when they moved to San Rafael melted away with the regaining of their long-time friendship.

Seydi Cifuentes • Jun 7, 2022 at 9:45 am

Great job Jose and Kayla! Stories like these need to be told. Just like this one, there are many more to be told.