The Black Student Union at a Not-So-Black School

May 17, 2023

When Stephanie Fayette was first called the N-word at school, she didn’t know what it meant.

However, it was only the first instance of many, and she quickly learned the slur’s meaning.

A recent immigrant from Haiti, Stephanie was facing all the challenges one would expect. She did not speak the language. She knew no one except a few family members. She had to navigate a school and an environment completely foreign to her.

Even at San Rafael High School, a place with a thriving community of immigrants, Stephanie still felt isolated and unheard. Most of the other immigrants came from Central or South America. While Stephanie spoke Haitian Creole and French, her ELD (English Language Development) classmates spoke Spanish or their own indigenous languages. The resources designed for newcomers were tailored to their needs, not Stephanie’s. No one, not even her teachers, could understand her.

In addition to all of this, Stephanie was also forced to reckon with her Blackness for the first time. Coming from a country where an overwhelming percentage of the population is Black, she was not used to experiencing discrimination because of the color of her skin. But being in America was a different story; she was called slurs at school, followed in stores, and constantly stereotyped and judged by others. It was shocking, and it was challenging to navigate alone.

However, Stephanie was resilient and determined to overcome the adversity she faced. She spent her free time learning English and Spanish so she could communicate with those around her. She joined leadership classes like Link Crew in order to have a voice on campus. She spoke up, told her story, and advocated for change.

Stephanie graduated from SRHS in 2021. Today, she studies social justice at the College of Marin and works as an instructional assistant at Laurel Dell Elementary School. Her experiences in high school, both negative and positive, shaped and inspired her. She wants to combat the inequity she has faced and support other community members like herself.

“I’ve lived through [racism], and it was painful,” says Stephanie. “I don’t ever, ever want to see someone going through this, at least not when I can do something about it.”

One of the hardest things for Stephanie during high school was not having access to a safe space or a community that understood her. “Sometimes you can go to a safe place where you don’t even need to talk,” she explains. “Just the presen

ce, just being there, is what’s important. And there wasn’t that. It wasn’t an option.”

Stephanie may not have had a place to turn to during her time at San Rafael High School, but this is no longer the case for today’s students. Now there is a space where Black students can go to find support, a space where they can connect with their community, a space where they can be themselves. That space is the Black Student Union.

Welcome to the Black Student Union

Every Monday (sometimes every other Monday) Black and non-Black students alike gather in room LA 219 during their lunch period for meetings of the Black Student Union, or BSU for short. Together they learn about Black culture and history,

discuss the challenges facing Black students, or just hang out and get to know one another.

“It’s not a downer, it’s

a very prideful club,” says Tegan Mack, a junior at SRHS. Tegan founded the BSU and served as one of its first presidents. This year she moved into the role of vice-president, although she recently stepped down due to personal time constraints. However, she remains an active and eager participant in the club. “The BSU is just fun […] I like the community and fun stuff that we do in the club,” she says.

“They’re super organized. They have really good ideas. I think they act on their ideas well,” adds Daniel Allen, a US history teacher and the BSU’s faculty advisor. “That’s definitely ideal for a group, that they feel really passionate about the mission and they’ve acted on many of their goals.”

The BSU is an example of what is known as an affinity space, or affinity group. Affinity spaces form around a group of people with similar goals or shared cultural and social identities, including race, ethnicity, religion, gender, and sexuality. In the BSU, this identity is Blackness.

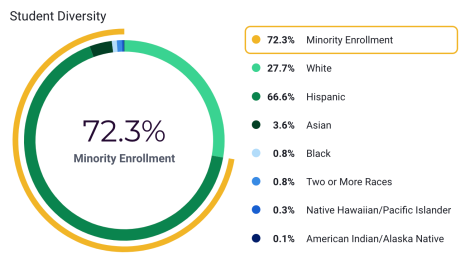

Black students represent a significant minority of both the school population and the local community. According to the most recent estimates from the US Census Bureau, Black people make up 2.9% of Marin County’s population. This drops to only 1.6% for the city of San Rafael specifically, a paltry number compared to the percentage of the city that is white (56.5%) or Hispanic/Latinx (31.2%).

At SRHS, only 0.8% of the student body is Black. This doesn’t account for biracial Black students who would be included in the category of “Two or More Races,” but even this category only represents another 0.8% of students, and not all multiracial students are Black. With an enrollment just under 1300 students, these percentages amount to a rough estimate of only 10 to 20 Black students in total on campus.

These demographics can be traced to a history of systemic racism and anti-Blackness in Marin County. Racist housing practices like redlining and racial covenants have been used to enforce segregation and keep Black people out of Marin. Many of those who do live here have been relegated to the historically Black community of Marin City.

The purpose of SRHS’s Black Student Union is to elevate and emphasize Black voice, to advocate for the rights and representation of Black students. At a school where Black students are such an extreme minority, some might disregard a BSU as being unnecessary. Why do Black students need a whole club if there are only a handful of them?

It is precisely because Black students are so underrepresented in the school community that the BSU is essential. With such a small population, the challenges facing Black students are often overlooked or disregarded. The BSU allows Black students to organize around these shared struggles. While it’s easy to ignore one Black student, it’s much harder to ignore a whole group of them.

“To just push out and make our voices known is really important,” says O’Marion Beard, an SRHS senior and a member of the BSU. “If we don’t do it, no one’s really going to do it for us.”

“BSUs provide a sense of community and advocate for the needs of Black students,” adds Raquel Mack. “They contribute to a more inclusive and equitable learning environment for all students.”

Mack is Tegan’s parent and one of the founding members of Save Your Six, a civil rights advocacy organization working to protect the Title VI rights of students. Title VI is a part of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, and national origin in federally-funded programs. Save Your Six recently led two trainings for SRHS staff.

“It’s very important that Black Students have access to BSUs particularly in schools where they make up a small percentage of the student body,” explains Mack. “[BSUs] help counteract isolation, amplify voices, increase cultural competency, encourage diversity and inclusivity, foster allyship, and build confidence and empowerment.”

“Sometimes Black students need a space to connect and just breathe, without having to navigate people or a culture that might make them feel as if they don’t belong,” adds Dr. Lori Watson, the founder and CEO of Race-Work.

Through Race-Work, Dr. Watson leads a variety of seminars and programs aimed at creating dialogue around race and providing institutions with the skills and tools necessary to become more anti-racist. This includes her program SLAM! (Student Leader’s Anti-Racism Movement), which serves to educate and empower student leaders to advocate for racial equity in their schools. Dr. Watson facilitates SLAM! in numerous middle and high schools in and outside of California, including SRHS.

“A BSU should be a place where Black students are able to come together to talk about their experiences and any matters that are uniquely important to them,” says Watson. “This doesn’t mean that all Black students are a monolith, however, because of the construct and impact of race, they might possibly share more commonalities than not.”

A Brief History of the BSU

The BSU at San Rafael High is part of a rich tradition of community organizing and advocacy among Black students. In fact, the history of the Black Student Union is far more local than many may realize. The first BSU was started just across the bay at San Francisco State University in 1966.

There had been many examples of Black students organizations, especially throughout the civil rights movement, but this was the first time that a group adopted the “BSU” moniker, a label that quickly gained widespread popularity. The club was predicated upon the idea that, even in a predominantly white institution, you could bring Black students together to collectively advocate for their academic, social, and institutional needs.

The current BSU at SRHS is not the first of its kind either. A previous BSU was founded during the 2004-2005 school year by Shelly Clermenco, the club’s president. Although Clermenco graduated in 2006, she believes the club ran for a few more years, led by younger members.

This BSU first began because Clermenco noticed a lack of safe spaces on campus for Black students. After conversations with her friends and mentors, she decided to create the space herself. “It just kind of all happened organically,” she says.

Most of the members of this BSU were Black women, including Clermenco’s sister and many of her friends. Today, many of them remember the BSU as a “sisterhood.”

“I felt like as a Black young woman, and especially a Haitian woman, I wanted to have something where I felt like I belonged,” says Clermenco. “We needed a space where we could forget about the troubles that we had at home and maybe discuss it with the group.”

Many of the students in the BSU came from christian households and shared similar experiences, but their backgrounds were also very diverse. Some of the students were African-American, some were Haitian, and one even hailed from Nigeria.

“Not all Black people eat the same food, not all Black people speak the same languages,” says Clermenco. “It was beautiful to come together and eat each other’s food and talk and just kind of share experiences and have fun with it.”

She adds, “BSU is so much deeper than just being Black because we all, because of the history of slavery, we were all very different and we were able to learn more about each other’s culture.”

In addition to building community, Clermenco’s BSU hosted various events to raise awareness of Black culture and Black history, including a poetry slam and a step show. “We just kind of did the best that we could to give ourselves the exposure that we felt other students in the school needed,” says Clermenco.

A few weeks ago, Clermenco returned to SRHS to speak to the current BSU. She was surprised to find that the campus and the BSU had changed significantly since her time. She felt that SRHS was more diverse and had more Black students when she attended.

Even though her BSU was smaller, Black students had a stronger presence. Today’s BSU is larger and has a more diverse membership. There are more non-Black students, including many white and some Latinx students.

Clermenco was impressed by the current BSU’s efforts to tackle injustice and reach outside the scope of just their school community. Her BSU did not have the capacity or the support to be as active. “We were fighting for a voice because our group wasn’t really supported, it wasn’t really encouraged,” says Clermenco. “I feel like there is much more support [today].”

Clermenco is still connected with many of her peers from the BSU. A number of them went on to become active members in collegiate BSUs. After Clermenco’s BSU came to an end, San Rafael High did not see another Black Student Union again until 2021.

Tegan Mack founded the new BSU at the end of her freshman year, during online learning. However, it didn’t really build a presence until school returned in person the next year. Tegan was joined by fellow sophomore Marguerite Walden-Kaufman, and together they led the club as co-presidents.

The inaugural year was challenging. The club had yet to gain a consistent group of members and hit its stride. The summer after this first year, Marguerite reached out to Dr. Watson for guidance on how to make the BSU more effective. Dr. Watson connected her with local Black leaders who were able to mentor her.

Coming into this year, Marguerite took over as president of the BSU, and Tegan as vice-president. They reached out to Principal Dominguez to get the administration’s support, then focused on advertising and creating a fun club environment to draw in new members. They successfully built a consistent and motivated membership base, which has been essential to the club’s success.

Young, Black, and Alone

For both Marguerite and Tegan, one of the best parts of the BSU has been its presence as a space for Black students to connect and build community.

“I think the most important thing we’re doing right now is bringing people together,” says Tegan. “It’s cool to see other Black students in proximity to me because I hang out with my friends, but I don’t hang out with them, so that in and of itself creates community.”

“I just felt so lonely at times,” says Marguerite, recalling her experience at school before the BSU. “I don’t really like being at a space where I can’t talk to people about a big part of my identity.”

Growing up in Marin, Marguerite was not used to seeing people who looked like her. She attended Glenwood Elementary School, where there were few Black students. She distinctly remembers when another Black girl joined her fourth grade class. It was the first time she didn’t feel so alone.

The biracial daughter of an African American mother and a Jewish father, Marguerite has a lighter complexion and a unique lived experience. Unlike people who are more visibly Black, she is often assumed to be white. This comes with its own privilege, but it also makes her feel unseen and insecure in her identity, as if she isn’t Black enough.

Marguerite’s most notable feature is her hair; prominent curls serving as a visual reminder of her Blackness, even when her skin tone doesn’t. Because of this, her hair has played an important role in her identity.

As a kid, she tried to copy her white friends by brushing it out. “I thought that I was supposed to look like everyone else, act like everyone else,” Marguerite says. However, what made her peer’s hair sleek and silky only made hers big and poofy.

This used to make Marguerite feel upset and isolated, but her perspective has shifted with time. After exploring her identity and self-expression in high school, she realized that conformity shouldn’t be her goal. “I was able to be like, ‘Hey, this is who I am, this shouldn’t change,’” she explains.

One of the most important role models in Marguerite’s life has been her mother, Edie. She exposed Marguerite to Black culture and taught her what it meant to be a Black woman. Marguerite often felt most connected to her community when she was around her mother’s extended family, especially with the lack of other Black students at school.

Edie taught Marguerite to know where she comes from, to never run from her Blackness, and to always acknowledge other Black people. These values have guided Marguerite in her leadership of the BSU and have been paramount to the club’s success.

Putting Principles Into Practice

The parts of Black culture Marguerite could not experience firsthand, her mother supplemented with outside resources. While stuck at home during the pandemic, Marguerite’s family passed time by watching documentaries and movies about the Black community. They learned about every historical event and figure, from Booker T. Washington to Biddy Mason.

This inspired Marguerite to spend time doing even more research on her own. Learning about her culture helped her feel closer to her identity and community.

Marguerite brought this practice with her to the BSU, teaching Black history through presentations, icebreakers, games, and friendly competitions (including a few heated rounds of Kahoot). Most members I spoke to highlighted this as one of their favorite aspects of the club.

When Marguerite feels insecure in her Blackness because she is biracial, her mother is quick to remind her that “if you’re Black, you’re Black.” Historically, this adage comes from the one drop rule, a practice used to categorize anyone with even “one drop” of Black blood—or any Black ancestry—as a Black person.

Edie encourages Marguerite to reclaim this idea. If the world will always put her Blackness first, so should she. No one can strip her of her Blackness, but she can’t run from it either. She must embrace her identity, even when it isn’t easy.

Marguerite knows what it is like to doubt her identity, and she doesn’t want others to feel the same way. In the BSU she maintains an open environment because that is the kind of environment she wants to be a part of.

The BSU is open to students of any race who are interested in learning about and advocating for the Black community. While the needs of Black students are always prioritized, non-Black students are welcome if they remain respectful and engaged.

“I think it’s great that people who are not Black are in the club and are as interested as they are because it’s so important to have people of other races and cultures learn from each other,” says Kiara Velez, a junior at SRHS and the BSU’s secretary.

Kiara is a non-Black, Filipina student. She likes that the BSU allows her to support her Black peers, while learning about their experiences and engaging in dialogue about race. “Having a space where you can communicate your life and your experience in a safe way to other people who are willing to listen and willing to understand is so amazing,” she says.

Not only does being in the BSU expose non-Black students to new perspectives, their presence also helps generate support for the club. At SRHS, non-Black students make up a significant portion of the BSU. This is helpful at a school like ours, where it can be challenging to maintain membership because the population of Black students is so small.

Edie also “drilled” into Marguerite that she must always acknowledge other Black people when she sees them in public, whether with a simple nod or a brief greeting. More than a pleasantry, this sends an important message of respect, understanding, and support.

Marguerite made this practice an intentional part of the BSU’s culture after the first meeting of the year, when another member passed by her in the hall without saying anything. At the next meeting, she explained what she expected of the club’s members.

“Everyone you see in this meeting, you should be able to say hello to each other when you see each other outside of this meeting,” she said. “That’s how it’s got to be in an environment like this.” Since then, acknowledgement between club members has been consistent.

“In a world where we often don’t get seen, it’s important to intentionally see each other,” she explains.

The Petition

In November, the BSU was thrust into the spotlight after Marguerite circulated a petition calling for the reinstatement of Royce Huges, former head of campus security at San Rafael High.

Royce was temporarily suspended from his position last semester after an incident with a student. The student verbally assaulted Royce with offensive racial slurs, including the N-word. Royce allegedly knocked a tray of food out of the students hands in response. The student was suspended, but soon returned to campus. Royce has since moved on from SRHS.

The petition received 1,192 signatures by the time of this article’s publication. Penned by Marguerite and backed by the BSU, it called for the reinstatement of Royce, the referral of the student to SRHS’s Peer Advocate Team, and for administration to bring in an outside organization (such as the NAACP) to lead a school-wide assembly.

The petition’s rapid spread garnered attention, resulting in coverage in the Marin Independent Journal and the Pitch, Archie Williams High School’s student newspaper. The petition was also promoted by Heart Blaster Inc., a nonprofit organization dedicated to supporting youth through advocacy, education, art, and other resources. It even led to a guest appearance on local radio show Tay Radio Marin for Marguerite and Bela Temple, the BSU’s social media coordinator.

In the petition, Marguerite emphasized Royce’s importance to the Black student community as one of very few Black staff members on campus.

“Not only [is Hughes] a beacon for us Black students on campus, but seeing a Black man in a position of authority and respect allows us to see a part of ourselves and believe that we too might be able to achieve bigger things,” read the petition. “Seeing a person we hold in such high regard be subject to consistent hate speech has a tremendously negative impact upon us.”

Several other students echo this sentiment. “It really didn’t feel right because Royce is a member of this school that a lot of people actually like,” says Bobbie Knowles, a junior at SRHS and a member of the BSU. “For him to go through that situation and be so loved at this school, it just […] kind of broke me. I didn’t like how that went down.”

After spending freshman year online during the pandemic, Bobbie came to SRHS as a sophomore knowing few of his classmates. Royce went out of his way to introduce Bobbie to other students, both Black and non-Black. This helped Bobbie feel more connected and comfortable in the school community.

Royce was the adult that Bobbie trusted most. He was a role model, someone Bobbie could go to for advice. To lose this confidant was challenging and frustrating.

“Of course I have a relationship with my other teachers, but it’s not the same,” he explains.

“I really liked Royce,” adds O’Marion Beard. “He sort of knew everyone, he was like a glue for the school.”

Students were especially upset by the lack of transparency from administration surrounding the incident. However, administrators had their hands tied by legal obligations. A few weeks after the incident, Principal Joe Dominguez sent a message about the incident to the school community in the weekly email blast “This Week @ SR.”

“I want to remind everyone that while I prefer transparency and communication, the Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act and personnel privacy prevented me from doing so in this instance,” Dominguez explained in the message.

Though he couldn’t disclose any details about the situation, he affirmed that “no person should ever experience racism and we will not stand for hate speech.” He also acknowledged the pervasiveness of racism and hate speech at SRHS, and he committed to working towards better “education and accountability” around these issues.

SRHS and the Racist Language Problem

“I hear the N-word used all the time,” says Bobbie. “I mean at this point it doesn’t really bother me because I hear it so much.”

Bobbie moved to San Rafael in 8th grade. He began attending Davidson Middle School and was very surprised to hear non-Black students using the N-word so frequently (a problem that has persisted through high school). It was something he never dealt with at his previous school—Hillview Junior High in Pittsburg—where most students were Black.

Generally, Bobbie hears the N-word used by Latinx students. He suspects these students grew up in communities where the word is used frequently, and they don’t understand its meaning or connection to the history of slavery and anti-Blackness in the US. Though white students also use the N-word, they have learned not to say it around Bobbie.

Dominguez has taken steps in an attempt to address the problem of N-word usage on campus. He attended a BSU meeting, as well as met with club leadership several times, before bringing in Save Your Six to deliver two one-hour training sessions to the staff.

The trainings were aimed at helping staff understand their legal requirements in interrupting racism and any other instances of hate speech in the classroom, as well as ensuring they feel well-equipped to do so.

“It felt really great to get all the teachers on the same page regarding Title VI, what it is, their responsibilities and who to report racial discrimination to in order to properly address it and stop it from continuing,” said Raquel Mack, who helped lead the trainings. “We talked a lot about racist language and how to respond to it in the moment that they overhear it or are notified of it.”

Mack was happy to see Dominguez taking action on the issue. “Principal Dominguez has expressed how important it is to him that all students can attend SRHS feeling welcome, safe, and supported,” she says. “I’m encouraged that he is taking steps to shift the culture toward real accountability around Title VI.”

“We do have a lot of work to do as a school community to talk about behaviors,” reflects Christopher Simenstad, an English teacher at SRHS, regarding the usage of racist language. “We’re avoiding doing really the hard work if we’re just expecting teachers in the classroom to fix this problem.”

“There are some students who will do what they want because they don’t think there are any consequences,” he says. “Can you have a respectful school environment if a certain number of kids are allowed to behave unchecked?”

Simenstad believes if we hope to change student behavior, we have to make our expectations for students clear. “If we’re going to not only coexist, but come together as a community where we value learning and achievement and understanding opinions that are different than our own […] there has to be a school culture that supports that,” he says.

The current disciplinary policy on use of hate speech (including the N-word or any other slurs) involves a three-day suspension as a first-offense consequence. Dominguez began enforcing this policy as soon as he was aware there was a problem on campus.

“I have my own opinions about whether or not suspensions work,” he says, “But for me it sends a clear message that we’re just not going to tolerate this on campus, so that’s what we’ve been doing.”

Dominguez hopes to follow-up next year by providing staff with more resources and sentence-starters for interrupting racism they see from students. He also wants to educate students about the history of the N-word and why it (or any other racism) is not tolerated on campus. In the long-term, Dominguez envisions a school-wide network of student activists who stand up to racism.

“I would love for students to know what to say if they hear it and kind of empower themselves to interrupt it in that moment, because really that’s the key,” says Dominguez. “Adult ears aren’t always around, and so if students hold each other accountable, that’s just going to help change the culture of the campus.”

It is yet to be seen if these efforts will be successful in addressing the problem. Beyond this, change is still slow to come. What happened with Royce is not just one unfortunate occurrence. Rather, it is emblematic of deeper, systemic racism that plagues our community. The lack of Black teachers and staff, the use of racist language, and the dismissal of Black students are all facets of a larger culture of anti-Black racism.

A Tale of Three BSUs

Our campus is not the only one struggling with these problems. Sarah Mondesir, a senior at Terra Linda High School and the president of the school’s BSU, recalls an incident just a few months ago where she and another Black student were called the N-word twice by a substitute teacher. The situation was addressed by administration and the substitute cannot return to campus, but it left Sarah feeling shaken.

“It’s just things like that, that really impact us [Black students],” says Sarah.

The demographics of Terra Linda High are very similar to those of SRHS, its sister and rival school. Black students represent only 1.6% of the student population there. Another 5.1% of students are multiracial, while 46.3% are Hispanic and 40.2% are white.

Sarah founded the TLHS BSU during her junior year, alongside a friend who has since graduated. Similarly to Marguerite, she was inspired by her desire for a safe and welcoming community at school.

“Coming back from being at home for a long time, I realized that something that I really needed was a community and a space where I can feel really safe and valued,” says Sarah. “I’ve really valued having a BSU and having that connection with different Black students on campus.”

Like the SRHS BSU, Sarah’s BSU does everything from hanging out and creating community to advocating for change on campus. The club ran programming during Black History Month and now hopes to organize a few larger events, including a celebration of Black girls and a retreat for BSUs across the county, led by Dr. Watson.

Sarah walks a thin line between working on advocacy and building community. Her BSU has struggled with membership after many of their members graduated last year. As time passes from the George Floyd incident and the resurgence of the Black Lives Matter movement, Sarah feels racism is becoming less pressing in the minds of students. It’s a challenge for her to keep students engaged.

“Me and my friend group, we definitely try to go out of our way to reach out to different Black students,” Sarah says. “But there are some students who are just not interested. That’s something that we had to face and realize.”

As Dr. Watson explains, “Some students are empowered by membership in the BSU, and honestly, some Black students shy away from it, not wanting to be associated with it, believing that they have to do what’s necessary to fit in with the dominant culture—some of that is a survival tactic.”

Marguerite has encountered this as well. It’s challenging to garner membership among other Black students, and even when they do join, not all of them are comfortable speaking out or focusing on advocacy. Some prefer learning about history or just building community.

“Over time something I’ve learned is that your group is only as strong as the people in it,” Marguerite says. “I’ve kind of had to recognize that it’s okay to have a BSU sometimes that is more about an affinity space.”

Marguerite’s strategy is to focus on creating a safe and welcoming environment in the BSU. If people enjoy and feel comfortable engaging in the club, eventually they may be ready for bigger actions. In the meantime, Marguerite can work on advocacy outside of club hours, like when she wrote the Royce petition.

“It just goes back to knowing your audience,” she says.

These phenomena extend beyond the high school level. Black Student Unions at colleges and universities face similar challenges, including the BSU at Dominican University of California, a small, private school in San Rafael.

“It’s really hard to get all the Black people together, and I have to maintain a relationship with all of them,” says Zay Carter, a sophomore studying business administration at Dominican and the creative marketing officer of the BSU. Though Zay works hard to engage Black students in the BSU, they aren’t always receptive, and the population is small to begin with.

Demographically, Dominican follows a similar pattern to SRHS and TLHS. Only 4% of the students are Black and 4.3% are multiracial, while 20.7% are Hispanic/Latin, 20.7% are Asian, and 33.2% are white.

Black students at Dominican are aware of one another. It’s impossible not to be, with so few of them on campus. “If there’s a new Black student on campus, everyone notices,” says Zay.

Though they are supportive of one another, Black students tend not to “huddle up,” as Zay puts it. The BSU allows Dominican’s Black population to come together, creating connections that may be lacking in other parts of their college lives.

Still, Zay says that many Black students have the mindset of “what am I getting out of this, other than you telling me that I’m Black and I already know that.” The BSU’s leaders have to demonstrate the club’s value and incentivize them to come.

“I can’t just throw an event and then not worry about how it’s going, or I can’t just call a meeting, have everyone come, and then we don’t have anything planned,” explains Zay. “I have to have a set thing to do that’s fun and engaging.”

The Dominican BSU hosts various events, including kickbacks, karaoke, and trivia nights. Their goals range from simply building community to raising awareness and educating others about Black culture. A notable event is their “Hair Talk,” during which students share resources for those with curly hair.

Student engagement is key to the club’s success, but is daunting with a smaller membership base. Zay aspires to emulate other student groups like the Kapamilya Club, Dominican’s organization for Filipinx students which has upwards of 80 members.

“You definitely can’t ignore 80 Black people, but it’s way easier to, not ignore, but maybe almost forget sometimes that you’re there, when there’s only say 20 Black students that barely make it to meetings, barely know what’s going on, barely know anything about a BSU,” says Zay.

Recently, the Dominican BSU held their first Black Excellence Gala on April 21st, a part of their effort to diversify engagement and host larger-scale events. They also hope to become a stronger presence in the community by getting involved with local advocacy and service.

False Advertising

Speaking with the BSU leaders at each of these schools—San Rafael, Terra Linda, and Dominican—I discovered commonalities between not only the clubs, but also the institutions they belong to. The most noteworthy one? Each school markets itself as very racially “diverse.”

It’s true that each school has a student body that is majority non-white. Compared to other schools in Marin County whose student populations are predominantly white, this is significant.

However, having non-white students doesn’t necessarily equate to racial diversity. The non-white populations at these schools are almost entirely Latinx, or in the case of Dominican, Latinx and Asian. Students of other races, such as Black students, are severely underrepresented.

“There is this idea that we have diversity on campus. That does not exist, strike that out,” says Marguerite. “Diversity is when you have multiple different groups of people of different races on campus, of different ethnicities, and that’s not the case. You see typically people that are Latinx, people that are white, and that’s pretty much it.” She adds, “We’re publicized for being a school that’s diverse, when really we’re publicized for being a school with a lot of Latinx people, and those are two very different things.”

At Dominican, Zay works in the admissions office, where he is often instructed to emphasize the school’s diversity. However, he feels that making this blanket statement is deceptive.

“They’re not putting out that there’s only 3% Black students on campus,” Zay explains. “That’s something that I want to know if I’m applying as an African-American.”

The distinction between talking about a school as “diverse” versus majority non-white may seem insignificant, but this viewpoint can have seriously negative implications for Black students. Often, it leads schools to lump all their students of color together.

While all people of color experience racism in some form, the kind of racism they experience varies widely. Non-white students of different races can find solidarity with one another, but they ultimately have very different challenges and needs.

“Think about how historically, people would come here from other countries and sue to be white. Even today when people immigrate here now, there is a desire to assimilate into whiteness,” explains Dr. Watson. “Everyone gets the message that Black is the thing to avoid, to fear, to hate in some instances. This occurs not just from the dominant group but from other groups of color as well.”

Take San Rafael High, for example. Though Latinx students face institutional racism, they make up the majority of the student population. For SRHS to fail Latinx students would be to fail most students, so administration is incentivised to create change. As a result, Latinx students have access to a wide variety of resources and a vibrant community they can connect with for support.

On the other hand, because there are so few Black students on campus, their struggles are frequently overlooked. They encounter racism and anti-Blackness from both white and Latinx students alike. They are isolated from other Black students, leaving them alone to advocate for their needs.

Bobbie Knowles explains, “Me and a latino student would probably not have the same problems in this school.”

When SRHS treats our students of color like a monolith, it becomes easy to pat ourselves on the back for combating racism and adequately serving all students. In reality, racism is alive and well on our campus and the resources that do exist are tailored largely to the needs of Latinx students, ignoring Black students completely.

“There is racism under the larger umbrella that needs to be addressed, and the specificity of anti-Blackness needs to be discussed differently…not as an either/or, but a both/and,” advises Dr. Watson.

Beyond the BSU

“A lot of things are weighted by the amount of people emphasizing its importance,” explains Marguerite.

One Black student can easily be disregarded. Even when just a few Black students come together, it becomes much harder to silence their voices. If even more students join, both Black and non-Black, they become impossible to ignore.

“They’ll believe us and they’ll listen to us if they see that it’s actually a lot of students at school that feel a certain way,” says Tegan Mack.

The BSU gives students a chance to make this happen. As Dr. Watson says, “When the BSU is done right, it can play such an important role in the lives of Black students by providing a unifying experience that some don’t even realize they need.”

This power is not limited to Black Student Unions. Students can create affinity over any shared identity, be it race, religion, or gender identity. SRHS is home to several other affinity groups, including the Gender Sexuality Alliance (GSA) and the Underrepresented People in STEM Club (URPS). Most people I spoke to for this project said they would like to see more affinity spaces for other marginalized groups.

“I think that it is easy to feel lonely in your classroom if you’re the only person that looks like you,” says Dominguez. “Organizations like Black Student Unions really provide students with a safe space to maybe discuss their experiences and also just to support each other throughout their high school experience, which is already tough enough as it is for any teenager.”

This story isn’t just about being Black. It’s a story about being underrepresented. It’s a story about—even in a huge group of people—finding yourself alone. It’s a story about students who chose to come together in the face of isolation. It’s a story about students who refused to be quiet even when they were the only ones speaking up. It’s a story about how powerful it can be to build a community, no matter how small it may be.

Throughout the year, I have attended many BSU meetings, both before and after beginning the process of writing this piece. I am always struck by how welcoming and uplifting the space feels. The members of BSU know one another, they listen to each other, and they always find a way to get in a few laughs. They have built a camaraderie and community that is often absent from scholastic spaces. It is truly a pleasure to witness.

The BSU encourages everyone to come experience the club for themselves. O’Marion Beard says, “Coming at least once could help change your outlook […] You should go to at least just to check it out, to try it.”

Establishing the BSU at San Rafael High hasn’t been easy, but it’s here, hopefully to stay. Shelly Clermenco would like to see efforts shift towards ensuring the continuity of the club beyond any one president or set of members. “I think the key focus should be how do we keep passing the baton to the next student to keep it going,” she says.

“I’m glad [the BSU] is here,” adds Mr. Allen. “Hopefully it has some longevity to it.”

The BSU has limitations, but it also has lots of room to grow. Its members await this growth eagerly; they are excited to see what the future holds in store for the club.

“It’s not at its full potential yet,” says Tegan. “But that’s okay. I think I like where it’s going.”