Valuing the Laurel Dell Community

June 2, 2022

All quotes from Arcelia Chavez have been translated from Spanish into English for the purpose of this article. One teacher that I interviewed asked to remain anonymous; for the purpose of this article, the name Linda Smith will be used.

A moderately-deflated rubber ball slapped the asphalt and high-pitched giggles vibrated through the air, threatening to exceed frequencies audible to the human ear. The playground was bursting with proud little voices calling to each other in English and Spanish. A hot-pink tutu and a pair of triceratops sneakers were among the young fashion choices that caught my attention. I was overwhelmed by the warm feelings I had toward the little elementary school; there was something special about Laurel Dell.

“Ninety-nine!!”

My nickname echoed out from across the playground and I made my way over to my old principal, Pepe Gonzalez, who excitedly waved me into his office. We chatted for a while about how my family was doing and about his two little boys, who both attend Laurel Dell themselves. Sitting down to talk to Mr. Gonzalez, I still wasn’t sure exactly what I wanted to say about this school. I wanted to write about how special this place, this community, and these people are. But I also wanted to write about how undervalued all of that is, for being so spectacular.

The San Rafael City School District is a “District of Choice,” meaning that families can choose the elementary school to which they want to send their kids. And while just about all elementary schools have a sweet energy to them just by way of being full of little minds that buzz with wonder and curiosity, there’s something unique about Laurel Dell. I myself attended this school, a tiny public elementary school in San Rafael, CA. Many families in the neighborhood sent their kids to schools that were further away – and before the district adopted its District of Choice policy, many local parents even actively transferred their kids out of Laurel Dell – seeing the mix of cultural, ethnic, and language backgrounds at our school as a disadvantage. The student body at Laurel Dell is predominantly Latinx, with 64% of the students being categorized as English Language Learners according to San Rafael City School District data (provided by Lillian Perez at the district office). This ELL categorization doesn’t include students who speak English well enough themselves, but may not have family who do to help with their homework, etc – that percentage would be much higher. Students at Laurel Dell come from working families, with 87% qualifying for free or reduced lunch.

For me, the diversity in backgrounds provided an incredible opportunity; growing up, I was surrounded by the traditions of my classmates and neighbors, perhaps the most important of those traditions being the practice of embracing community (plus, our fundraisers always had the best pupusas and cumbia). Julia Levy, a former Laurel Dell Lion, told me, “I have always loved LD because the community was always so welcoming and kind.” Levy went on to say how grateful she was to have been exposed to an atmosphere that valued rich diversity, particularly in terms of language, at such a young age.

I spoke with Lauren Bartone, a parent of three former Laurel Dell Lions, and I asked her how she felt about the impact of the high percentage of ELL and socioeconomically-disadvantaged students on the school community. Bartone said, “I thought it was great. My kids had a different perspective on learning. They were able to gain some perspective and sense of scale about what real issues were, as well as a sense of privilege. Cultural differences were viewed as an advantage.”

Arcelia Chavez, a Spanish-speaking Latina mother who sent her son to Laurel Dell, said that she is “forever grateful” to have made the decision to send her son to Laurel Dell. Chavez cites Laurel Dell as a primary factor in her son’s academic success; he has now earned a college degree. For Chavez, the Laurel Dell community was striking in that “It didn’t matter to anyone where we were from, nor what language we would be speaking – we were all united like a family with no importance placed on race, language, or socioeconomic status.”

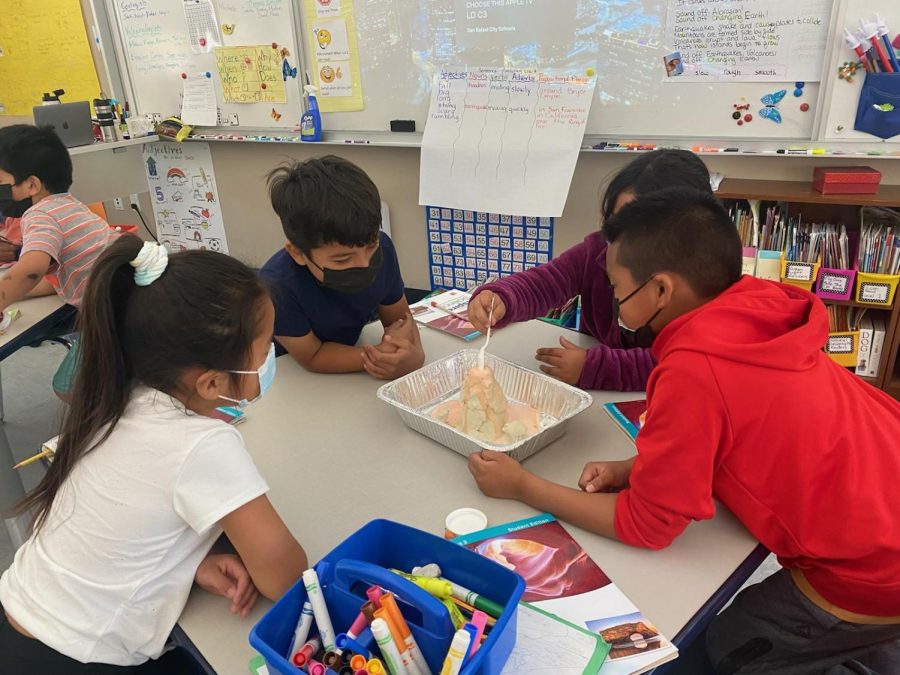

Beyond the cultural exchange and rich community created by Laurel Dell’s demographics, the high newcomer and ELL rate, combined with the fact that the community was made up of working families, created a need that led to unique programs being developed at Laurel Dell. The free, educational after-school program and the literary intervention specialist are prime examples, along with a general sense of dedication to meeting the vastly-different needs of each individual student.

When I sat down with Mr. Gonzalez, who is in his 12th year as the principal here, I asked him about Laurel Dell’s unique flair. Mr. Gonzalez told me that it’s all about “the community that is created by some of the most amazing teachers, staff, and families.” Gonzalez explained to me that, at this school, “Everybody just chips in and does what is necessary.” He talked about the families that will show up on their days off and how they averaged 20 volunteers per hour at their last event, an impressive rate for a school with a total size of only around 290 kids.

After answering my question, Mr. Gonzalez chuckled at me and pulled up a running list that he keeps of questions that are frequently asked by parents on tours. The touring groups tend to be composed of worried parents, who are primarily white. He attributes their anxiety and tendency to ask audacious questions to a “cultural difference”; the Latinx families that send their kids to Laurel Dell are “valuing our schools and trusting that […] we’re all trained and certified to do what we’re doing. They’re not going to question what we’re doing, typically.” That’s not to say that these parents weren’t invested – the dedication and fierce advocacy of the Latinx families was a huge part of what made Laurel Dell such a tight-knit and engaged school community. Mr. Gonzalez added that “they’re going to do what they need to do” to put time, energy, and money towards their kids’ education, “because that’s what they think is going to be the change for their future. And that goes back to that big sacrifice of our families that immigrate here – they’ve already acknowledged that they’re not going to get that education, they’re here to work so that their kids can have that next round of education, higher quality of life, and ultimately having their students attend 4 year universities.” Gonzalez explained, “If they value it, they’re going to do what you need to do to make it happen.”

My question about Laurel Dell’s unique offerings was similarly worded to a question at the top of Mr. Gonzalez’s tour question list, as visiting parents often required a lot of convincing and extra reasons to consider a school like Laurel Dell over less diverse schools with more affluent student populations. Mr. Gonzalez asked me in return, “Is it not enough to just be a solid public school that will do everything we can to give your kid a good education?”

Gonzalez also talked about Laurel Dell’s test scores. Although my general opinion is that test scores are not the best way to determine the kind of education students at a school are getting, scores are a metric that can help us figure out how well a school is performing in certain limited areas. For instance, in 2019, Laurel Dell had a higher percentage of Ever-EL students exceeding standards in CAASPP standardized testing than the district overall or the state. Ever-EL is a classification that describes students who are currently English Language Learners as well as students who began as English Language Learners and have been reclassified – meaning they’ve reached English Language proficiency. It does not include English Only students. 22% of Ever-EL students at Laurel Dell exceeded English literacy standards, compared to 6% in the district and 14% in the state. Showing similar trends, only 27% of Ever-EL students at Laurel Dell fell into the category of “Standard Not Met”, while 45% at the district level and 34% at the state level fell into this same category. Similar proportions can be found in CAASPP mathematics scores.

I asked Mr. Gonzalez about the school’s demographics. Gonzalez told me that when he arrived, the school was approximately 20-25% white, with almost all of the rest of the students being Latinx. The school is in a neighborhood that’s pretty mixed ethnically, so this proportion still indicated some reluctance by white parents to send their kids to Laurel Dell. He explained that 2-3 years into his time here, “People began jumping ship and it became very non-white, very Hispanic.” Gonzalez said that more recently, there’s been more neighborhood interest again. He attributes this to two different factors: the newly remodeled campus, and “the global worldview where equity and diversity are valued, and not only are they valued, but you’re actually going to do something about it.” He talked about white parents he had interacted with in previous years, who were reluctant to send their kids to Laurel Dell. “People were like, ‘Oh yeah, I value diversity. I value being woke and blah blah blah. But I need to go to this [other] school because it has this.’ And what they were truly saying was, ‘I need to go to this school because it’s more white than your brown school.’” There is still a chunk of our community that falls into that category; the school’s population demographics are still less white than the surrounding neighborhood, and several other elementary schools in the district are seeing similar issues of self-segregation. However, Gonzalez is seeing a slow change towards a more integrated student body, at least at Laurel Dell. “I don’t know where the shift happened,” he admits. “Partly it’s because we have a brand new building, partly because COVID made people realize that priorities are different, and partly because we are doing a really awesome thing here and people are slowly catching wind of that.”

When questioned about her choice to send her kids to Laurel Dell, Bartone told me that she never considered another school. “As a teacher, my philosophy is that you’re supposed to go to your neighborhood school, and live in your neighborhood and make it better in that way,” she said. Bartone went on to describe her conversations with other parents who chose to send their kids elsewhere, conversations which felt “racially coded.” She clarified that the skepticism from other parents just “affirmed that this was the right choice.”

However, talking to Laurel Dell families and faculty about how Laurel Dell was viewed by the community, the problematic results of this didn’t feel limited to a few ignorant parents asking insensitive questions on Mr. Gonzalez’s tours or deciding to send their kids elsewhere. I spoke with Linda Smith, a dedicated, long-time Laurel Dell teacher. “We don’t necessarily want to attract families who aren’t excited to send their kids here.” I decided to dig a little deeper into this problem in a more systemic sense, and consider the potential consequences of the Laurel Dell community’s value being overlooked – particularly with regard to the implications in terms of support from the district.

Lauren Bartone told me that Laurel Dell “was not and is not appropriately valued.” She was “outraged to see other schools, like Redwood [a high school in a neighboring district where Bartone teaches], with stable music and art programs, or other elementary schools with art teachers on campus, while we still had classrooms with broken windows, etcetera. There was a discrepancy in funding for arts, theater, sports, facilities, all of that.” Admittedly, part of that was an issue of the socioeconomic status of the parent pool that we were fundraising within. But this was not compensated for by the district either – Mr. Gonzalez described that, “When you go to these affluent schools, they have these art programs and dance programs and extracurriculars.” He explained that Laurel Dell wanted to offer students the exact same programs. “Just because our parents don’t necessarily have the resources to pay for them, we need to find alternative ways to give our kids the same opportunities.”

Linda Smith explained to me that the school only gets the district’s attention “when they want to change or critique something that we’re doing.” Smith added that, despite having notably high scores for the population that they work with, “No one ever comes to us to ask us for advice or to see what we’re doing that’s working so well.”

I heard a similar narrative from Mindy Green, a teacher who has been at Laurel Dell since before my time there. She taught me in 1st and 2nd grade. Ms. Green explained to me, “No one is paying attention unless the wheel squeaks. And not only do we not really have the time and resources to be effectively loud, it isn’t necessarily within our best interest to be squeaky.” Green extrapolated to say that Laurel Dell’s best strategy was to lay low, because attracting the attention of the district wasn’t always positive – but that strategy comes with a cost. When the district doesn’t hear complaints from a school, they are unlikely to prioritize that school. Issues of underfunding were unlikely to be addressed.

Pepe Gonzalez’s take was similar to Ms. Green’s; Mr. Gonzalez thought that, while no one is necessarily being intentional about giving Laurel Dell the short end of the stick, “Elected board members aren’t truly looking at what the schools look like, and aren’t making any policy changes at their level to fix that. I think as long as they’re not hearing from angry affluent families, they’re happy.”

I remembered feeling this way even when I was in school there. While our group of families was cohesive and connected, drawing from our shared commitment to preserving our unique community in order to power our efforts, most of that power was turned toward fundraising and organizing. And when voices were raised to challenge district or county-wide decisions, those voices weren’t necessarily heard. Meanwhile, the resourced parent bodies of the other schools had the advantage of more time (fewer parents working full-time or multiple jobs), fewer language barriers, the cultural tendency to question and complain, and perhaps a more receptive district office.

I remember attending the public session of a School Board meeting with my parents when I was in 3rd grade (in 2013), where a few LD parents were taking a stand against the addition of even more classrooms and students to the Laurel Dell campus. Parents at the board meeting read statements into the public record. One parent reached the podium and looked around the district office where the meeting was taking place, commenting that, “I think the last time I was here was when we were fighting to keep our Principal, Bob Marcucci, from being moved to Glenwood.” The silence that followed was thick and awkward, and the Laurel Dell parents in the room seemed to be enjoying every moment of it. Laurel Dell had not won the fight for Principal Marcucci, and his successor (who spoke minimal Spanish despite working with a majority of parents who spoke no English) had quickly been shown not to be well-suited for the job.

What I did not understand as well at the time was that this board meeting was a fight for equity. Laurel Dell already had by far the highest building density and student density of any SRCS elementary school (of which there are 6). In fact, Laurel Dell’s student density at the time was in conflict with California Department of Education guidelines, the school’s density being 228% of the recommended ratio. Laurel Dell was also not to code in terms of the number of toilets and drinking fountains per student. This proposal would only further the disparity. It was clear to me, even at age 9, that Laurel Dell was not the district’s priority. Whether the issue had more to do with the other schools’ tendencies to have parents with the time and resources to bother the district into doing what they wanted, or more to do with the demographics of Laurel Dell and to whom the district was willing to give the short end of the stick, is not an easy question to answer.

Laurel Dell parent Tracey Hessel closed out her statement at the board meeting with an invitation. “Perhaps due to its size, its history or its composition, we have an extremely committed staff and an environment in which our families with different cultural backgrounds and languages have come together to form a close knit community,” Hessel said. “We would like to invite the board members and the district administration to come spend time at Laurel Dell both to learn more about what we think is special about our school as well as to better understand our concerns.”

Nine years after this board meeting, standing up from my conversation with Mr. Gonzalez, I asked him what he wanted potential readers to know about Laurel Dell. Mr. Gonzalez said, “I want them to know that it is an amazing, awesome community with hardworking families that will do anything for their kids, and that our teachers and staff truly believe in every single kid.” Gonzalez smiled. “It really is a cool place,” he said, “and I put my own kids here.” Mr. Gonzalez was right – it was clear to me that the greater San Rafael community needed to hear how special Laurel Dell is. But beyond this, I also wanted the San Rafael community to hear how Laurel Dell has been neglected by the district over the years, and to understand what happens when those in power only grease the wheels that squeak.