Homework Isn’t Worth the Work

November 14, 2020

To high school students around the US, homework is an accepted, yet painful, fact of life. Teachers assign it, and students decide how much effort they are willing to put into it.

While there are some benefits to the additional practice that homework brings, it is often pointless and time consuming. In the end, the negative effects far outweigh those benefits, especially when given in large amounts.

Homework has passed through phases of popularity in the past century. In the early 1900s, teachers gave more work to improve discipline, but in the 1940s, people thought that it was restricting home activities, resulting in less work. This cycle repeated itself during the Cold War, when the fear that US children were not as smart as Soviet children caused an increase in homework. The tides turned against homework again in the 1980s as worries about mental health emerged.

As the battle continued, the amount of homework has slowly increased throughout the years. Currently, students are receiving around twice as much homework as students in the 1990s. Even kindergarteners, who used to receive almost no homework as little as 10 years ago, now have around 25 minutes each night.

Homework is a good way for teachers to follow through with lessons in class and has been proven to help students learn. The problem with homework appears when more and more homework is assigned each year without anyone realizing.

Developed from a combination of studies by Harris Cooper of Duke University in the 1980s, the “10-minute rule” says that as a general limit, there should be no more than 10 minutes of homework each night for each grade level. Since its creation, it has been incorporated into many school’s policies and is supported by the The National Education Association (NEA) and the National PTA (NPTA). According to the rule, 1st graders should have 10 minutes of homework and 12th graders should have 120 minutes of homework in total.

However, many students are receiving more than this. Some high schoolers have as much as five hours of homework to complete after school in addition to sports, jobs, and other responsibilities. While extra practice is important for comprehension and increases test scores, studies show that more than 80 to 100 minutes of homework is counterproductive. Students’ understanding does not increase and their test scores actually decrease.

This problem is increased by a disconnect between teachers. For high school and middle school students with different teachers for each class, each teacher tends to give at least 30 minutes of homework per day. Frequently, the teacher underestimates the amount of time needed for their assignments and forgets that their students are receiving homework from other classes as well. For example, if a student is taking six classes, even if each class only gives 30 minutes of homework, those minutes quickly add up to three hours of work. Despite this, some say that having large amounts of homework is necessary in and of itself.

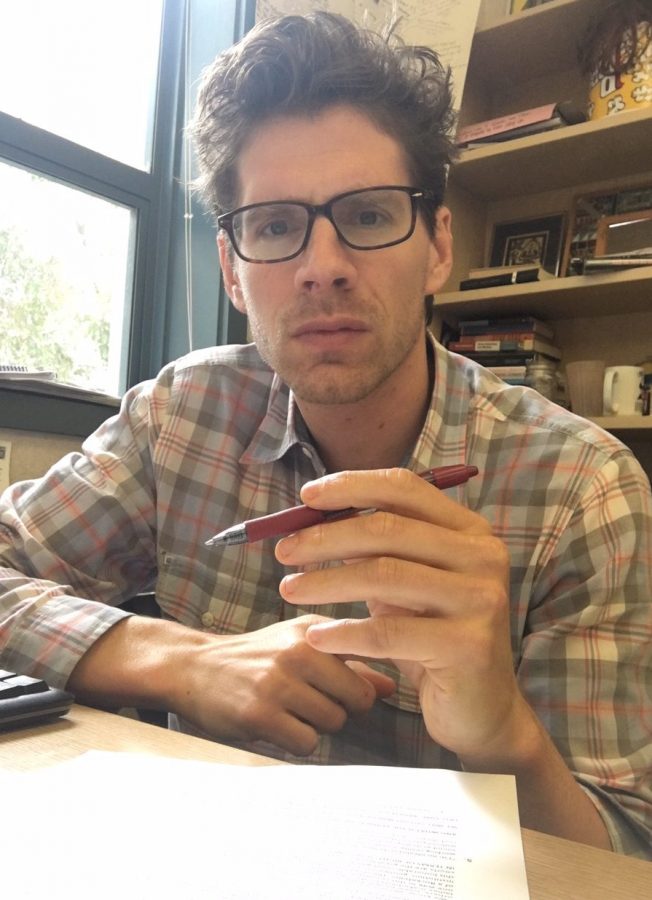

“It’s really, really important from a college preparatory standpoint to be ready to be able to do lots of homework; hours and hours and hours of work,” says David Snaith, a math teacher at San Rafael High School. Mr. Snaith believes that his homework assignments should take between an hour to an hour and a half each night. “If I don’t give you homework, I am not preparing you for college.”

While extra homework could make the transition to college easier for students, there are other parts of college that need to be prepared for. Many high school seniors are currently applying for colleges. These applications are as much work as a class, with pages of information, essays, and financial paperwork to fill out. The applications take huge amounts of time and hard work, and are extremely stressful for students. Homework takes time away from the application process as students have to focus on maintaining good grades in school while submitting their applications, or they risk not getting into colleges because of lower grades.

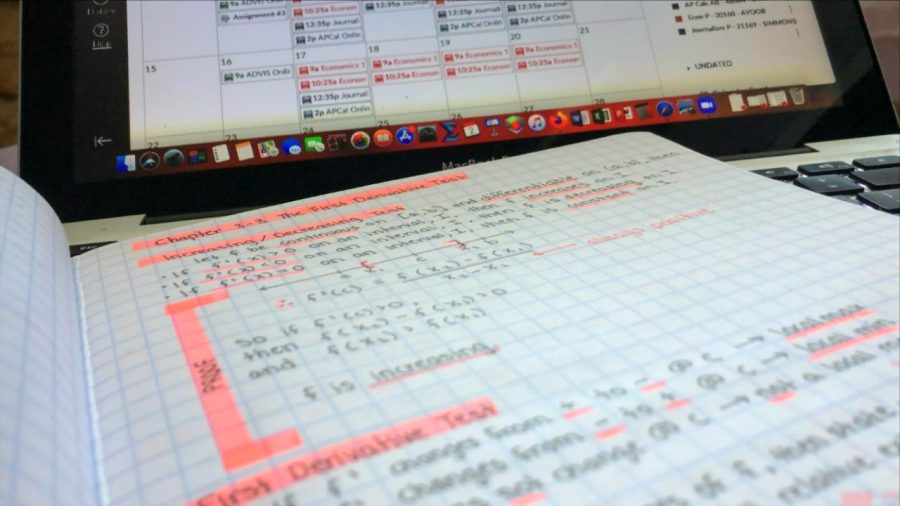

“It’s just trying to find a balance between those two things, because they’re both priorities, so finding the time for both is the hardest thing,” says Charlotte Lee, a high school senior at SRHS. “And you really cannot take a breather, you cannot get behind, especially with math.”

Charlotte, who is in Mr. Snaith’s AP Calculus class, says that she spends almost three hours a day doing her math homework, double the time that Mr. Snaith believes his homework should take. She is also currently taking Gov/Econ and AP Literature, bringing her total time doing homework each night to around five hours.

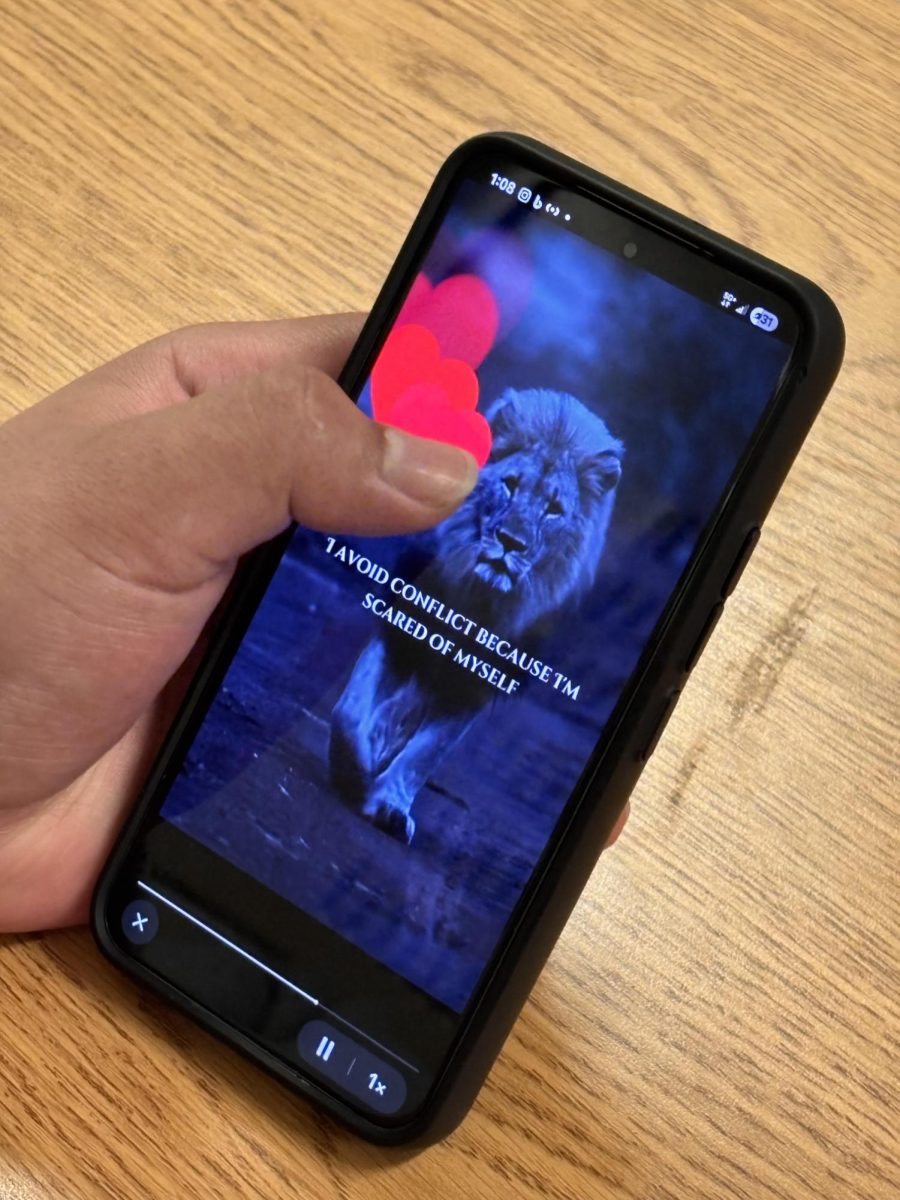

Other students in the class spend between two to three hours on the homework as well, which Mr. Snaith blames on phones and the distraction that they cause.

“Students say that they spend hours on homework, but they don’t,” Mr. Snaith says. “They spend hours looking at their phone while they have their homework open. In 15 years [of teaching], the stress level of students has gone up, and this is the only thing that has changed; I didn’t assign you hours and hours of homework.”

Although this might be true for some students, there have always been distractions for students in the form of talking, doodling, computers, and the television. If people are distracted, they will be distracted with or without their phones. Blaming phones groups all students together as irresponsible and immature, even those who don’t use their phones while doing homework. It also ignores the fact that many homework assignments now require the use of phones, especially during online learning.

Despite this, a good amount of students in the class do not use their phones for their math assignments and still take the same amount of time.

In addition to negative educational effects, too much homework is problematic for other parts of students’ lives. Students with three or more hours of homework reported physical symptoms of stress and sleep deprivation, with less free time to relax. If kids and teenagers don’t have any time for socialization and fun, who does? By increasing the amounts of homework for younger kids, the education system is taking away their childhoods and teaching them to hate school. Stressing out kids and teenagers with extra homework that doesn’t help them in any way is a waste of both teachers’ and students’ time.

Some people argue that school is a student’s job. However, the time that students spend doing their homework combined with actual school time add up to more than a normal work day, so the “job description” argument doesn’t hold up. High school students especially have responsibilities other than school.

Many have actual jobs, or need to take care of their younger siblings. And many students are part of sports teams, plays, and other activities that require huge time commitments. These activities are just as essential to their lives. Expecting them to give up these other responsibilities in order to spend more time on homework is completely unreasonable.

So why does homework matter? Too often it is only repetitive, busy work. Assignments like these are meaningless because the student either already understands how to solve most of the problems or none at all, which most likely will not change without additional teaching. Hammering away at pages of repeating problems isn’t going to explain the topic any better than an actual lesson. Long, repetitive assignments make students more likely to cheat as well, since they don’t have the time to complete them. In those cases, students are learning nothing from their homework, except how to avoid it. Good homework should be quality over quantity.

“Homework for the sake of homework doesn’t have benefits,” says Kelly Dupree, a teacher at Sun Valley Elementary School. “After a certain amount of time, you aren’t learning anymore.”

Mrs. Dupree assigns reading and math problems every day to her students, but makes sure that her assignments don’t take over 15 minutes to complete. She believes that homework is more about building life skills and good habits, especially in elementary school. When Ms. Dupree gives homework, she wants it to be meaningful.

Homework routines similar to Mrs. Dupree’s allow for students to learn, get the practice they need, and demonstrate their understanding to the teacher without long, tedious homework assignments. Although there are obvious differences between elementary and high school, both should have smaller, more meaningful assignments that would help students learn better.

When students are forced to spend hours on assignments, the only purpose it serves is to exhaust students and drain their motivation. With less homework, students would be able to spend more time relaxing and pursuing other interests, which would ultimately allow them to learn more. We shouldn’t accept it as a foolproof tradition at the expense of health and our happiness. A class can be just as rigorous, just as informative, and just as preparatory without homework.

William Coc • Jan 9, 2024 at 6:41 am

its really helpful for essays.