An Undocumented Student’s Path to Uncertainty

March 15, 2022

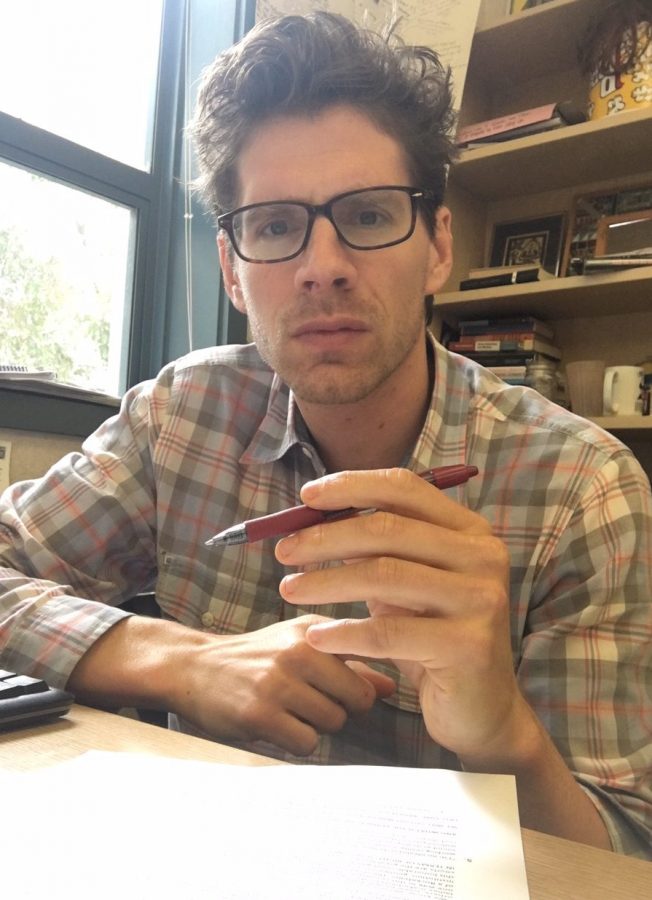

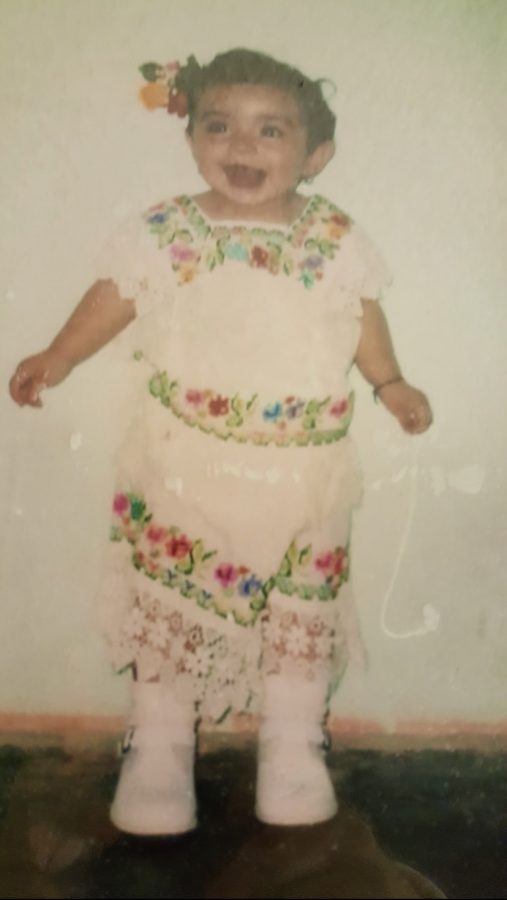

It’s an unacknowledged truth that immigrant parents want American kids. One to sashay around with like a prized possession. They have birthed this little spark of hope, one who will soon be suited up with ABCmouse and spend long hours at the kitchen table memorizing multiplication facts. I too was dressed up by my parents to make sure I was ready for the world that waited for me, but for completely different reasons.

At the age of 5, after experiencing an all-Spanish-speaking pre-k and not needing to learn any English after my arrival to the United States, I learned a cold truth. I wasn’t allowed to play Cops and Robbers with my classmates because I was, as they put it, “not speaking in their own language.” They were right. It’s hard to communicate with someone who only speaks Spanish, but I knew these kids since pre-school and we openly spoke Spanish there. What has changed?

I had a bigger dilemma though. Cops and Robbers wasn’t the only challenge. I lacked the armor to fight the dragon that was in my classroom constantly breathing fire at me for simply being confused at English grammar and conversational speaking. Every day, the dragon would wait for my parents to show up and then completely burn me.

The dragon, Ms. Barbel, hissed at my dad constantly about my confusion stating that I was “incapable of catching up to the kids at this stage” and being so disrespectful to her for not being able to understand her. My dad would look at her for all the time it took for her to finish her rant and then nod. He could not understand, but when we arrived home he would communicate my teacher’s disapproval of me to the eagle of my home: my mom.

I will never forget when my dad told her about my teacher’s nagging. Her thin eyebrows were furrowed together in concern as she reached over to me and told me, “Starting now we will make sure you don’t get the same comments again.” That day marked my journey of walking to and from the library every day with a sack of books and engaging audio files. I began to consume Judy B Jones and Magic Treehouse books hungrily and dealing with my own kitchen table nightmares of practicing long division and the multiplication table with my determined mother. Looking back at it now, it was also a time where the education system and my school have failed me and when my mom stepped up for me when no one expected anything of me.

My school and teacher failed me because it was clear at that time that I needed additional support, I needed an ELD Class and because I didn’t get that kind of support my mom had to step up for me. My teacher was irritated about something I could not control or received help with.

So early on, I learned what adults liked. If my name was associated with anything or floated around the religious chisme circles at night, I was going to make sure another child was receiving the negative commotion. I was, of course, not stepping on my cousin. What I mean is I decided to be an irritating overachiever. I spent most of my time alive making sure that my 4.0 GPA and my “stay at home bookworm” self fed the good girl narrative that was approved of by the immigrant community and the public. I was my cousin’s worst nightmares during get-togethers and despite everything the conversations always ended with scolding from her parents: “Danna has nothing. She has no papers but look at her do well in school. You have everything so it should be easier.”

During middle school, I learned how controversial my existence was and still is. It was a hot topic among history classes and any political debate on the news. I tried to approach this in a condescending manner. Look at politicians and my teachers having conversations about my right to exist in the US, this was true fan behavior! This, unfortunately, did not work. I still remember how suffocating it was for me to be in the middle of a debate about immigration. The moving eyes and the heat on my cheeks. Debates about whether you deserve basic human rights do that to you. This debate made me scared of ever letting anyone know about my undocumented status. I knew that I would not be perceived the way I worked hard to be perceived. I decided from that moment forward that my undocumented status would be my own little secret.

I’ve sat under my dad’s legs many times after he came home from work. As a little girl watching him watch the news every night was my routine and looking for an immigration reform was his. If you ask him he’ll answer that he was looking for an opportunity for me. I believe him. When DACA passed, I remember my dad making sure all my folders were sorted with general grades, horrible preschool drawings and medical check-ups. In junior year with an attempt to apply, I found out I came a couple months too late. I was already irritated with how off and on DACA was, so threatening, unstable, and excluding. This is a reality for a lot of undocumented students. We came a few days, months, and years too late. Thus, the government decided we didn’t dream enough after that. After the 2007 period I guess our wish to feel like existing human beings in this country expired.

I’ve worked all my life to be the perfect immigrant child. To be like the dreamers I saw on TV every night on Univision. My hard work, I thought, would scrub me clean of my undocumented status. I would not let America, who was behind me with a gun to my head, have the satisfaction of pulling the trigger for a mistake I made. I realize now that I was trying to erase my identity, any connection to it. Anything that would “give me away.” I hated myself for something I could not control, something that I was told to hate by people in my own community and in society.

It was hard to come to terms with that part of me. Part of it was resentment and pain of not belonging. Of not feeling connected to a certain group of people. Of feeling no particular connection to my birth country and wanting to be accepted by a country that didn’t love me back. Being undocumented is like that cheesy quote where it tells you, “To try and seize the opportunity or you’ll regret it.” Except, we can’t seize the opportunity because we are legally incapable of doing it but the regret is still there.

The college application process broke me. Suddenly, everyone had access to my secret. “Will you be filing for the FAFSA?” “No, actually I’ll be submitting the Dream Act.” I was afraid of disappointing people. I was afraid of being looked down on. I was afraid and I still am. It took me a while to understand that I wasn’t the issue. It was the culture of how undocumented students were perceived as and how little people expected of us.

I began noticing that the Latine quest to become a model-minority meant differentiating ourselves from our own people. First generation documented students were fed with the resilience of their parents and academic success videos of “I made it, you can make it too!” Undocumented first generation students walked egg shells every day to navigate that resilience with pressure to not only validate their parents stay but their own. Incoming undocumented students were pushed away from the whole thing. Those students became the “bad kids” and were and still are excluded from the academic push in our community. If I was despised at family meeting for providing clear proof of my capabilities despite my undocumented status then incoming students were hated for doing better than Jessica who “failed to seize the opportunity of having papers.” It was a race between who could represent the Latine community and who could not. Instead of allowing our ambition to bring us together, we have allowed it to exclude students from feeling valid enough to be acknowledged.

This country has become too comfortable with ignoring the root of our success. Of every immigrant child and child of immigrants. Someone planted a tree for us, did all the exhausting work, and allowed us to sit in the shade of the tree first. The media likes to ignore our parents. They like to pretend we were born set apart from our community, determined to be “better” because of the US. The US has never failed to make me feel inhumane while my parents made sure I received everything a person would to do well and be happy. My mom built her scholar and my dad made sure I could say yes to as many things as I could in life. My parents practically patted me on the head and believed in me, and that has kept me standing ‘till this day.

A lot of people wonder how undocumented students will navigate going to college while also knowing that they won’t be able to be employed in the future. Heck, I wonder the same thing. I’ve built a professional career in the art of dealing with uncertainty. It’s been in my life for so long that I’ve become indifferent to it. Some stories I’ve read about us have ended and started in permanent residency. Maybe I’m holding onto that story, hoping one day it can be my own.

Maybe the saying in my family has a hold on me: “It’d be sad to die in a country that doesn’t love you.” I think about it a lot. This saying has a grip on my dad, who’s determined to build a life for us in Mexico. I acknowledge that I long for a connection to the soil that helped me sprout. I hold onto my dad’s determination of moving us back in a few years and I also hold onto the idea of not knowing which will come. It’s the uncertainty of not knowing which will come first that becomes exciting. So, although I don’t know, it’s not as frightening as before.