The Pronoun Problem: Why We Cant Keep Misgendering Transgender Students (TRANSLATED INTO SPANISH)

December 9, 2022

“See what she did there?”

My teacher’s words stop me in my tracks. I forget the problem I was solving on the whiteboard, feeling a familiar shame. I came out as transgender and began using he/him pronouns over a year ago, but many people still use the wrong pronouns for me, especially at school. I face it everyday, and I am not alone.

San Rafael High has a pronoun problem.

“I get misgendered about every day, multiple times a day,” says nonbinary senior Rai Zelinsky Jobe (they/them). “It makes me feel really anxious and uncomfortable.”

“It makes me feel like shit. It really puts me off,” says transmasculine senior Jay Cates-Jackson (he/they). “I try not to let it bother me too much, but some days it just happens so much more frequently and I have no idea why.”

These students are transgender, trans for short, meaning their gender identity is not aligned with their sex assigned at birth. Trans people may be binary (male or female) or nonbinary (any identity beyond the gender binary). While the language used today to describe trans identity is a recent development, gender non-conforming people have existed throughout history.

According to a 2022 study from UCLA’s Williams Institute, 1.93% of Californian youth ages 13 to 17 identify as trans. For context, 1-2% of the world’s population is estimated to have red hair, so you probably know as many trans people as you do redheads.

Oftentimes, when trans people come out, they change their pronouns to better express their identity. As trans visibility in mainstream western society has increased, pronouns have entered popular discourse through conversations about gender identity and expression.

Common pronouns include she/her or he/him and the gender neutral they/them. Many argue the singular “they” is grammatically incorrect, but it has actually been used in the English language since the 1300s. Other gender-neutral pronouns include neopronouns, like xe/xem or ze/zir.

Using the correct pronouns for someone shows affirmation and respect of their gender identity. This is especially impactful for trans youth.

“If I’m correctly gendered, I’m hootin’ for joy […] I’m telling everyone in my vicinity,” says trans senior Conner Tate (he/him). “The bar is so low.”

As many institutions work towards trans inclusivity, asking for and using pronouns is increasingly encouraged. However, mistakes are still made often. Using the wrong pronouns for someone is called misgendering.

Trans people are misgendered constantly, whether unintentionally or not. It is most commonly done by cisgender people (cis for short) or those whose gender identity does align with their sex assigned at birth.

For example, Cates-Jackson is frequently misgendered at school, even by those who didn’t know him before he came out. Some people even make mistakes only after learning he is trans. “I feel like I need to just wear a nametag with my pronouns on it for people to understand more,” he says.

Recently, Cates-Jackson was misgendered among a group of friends, when a staff member referred to them as “ladies.” They say people use gendered language like this “all the time.”

Zelinsky Jobe shares this experience. “You don’t have to refer to a room as boys and girls or ladies and gentlemen […] you can just say everyone, or y’all, or all,” they explain. “People are just so averse to making any little change in their vocabulary.”

Usually, people who don’t know Zelinsky Jobe incorrectly assume their pronouns, but even those who are aware consistently mess up, despite Zelinsky Jobe’s attempts to correct them.

“It’s just annoying when people assume,” Zelinsky Jobe says. “I could wear a they/them pin, but even then, I wore those pins all throughout middle school and they rarely ever worked.”

Misgendering hurts trans students’ ability to express themselves authentically at school. “I really like wearing bright colorful outfits [but] that’s seen as a feminine trait,” explains trans sophomore Jared Goulding (he/him). “It’s either I give up my fashion sense and everything that I like about myself or I get misgendered.”

Tate agrees, “I love to on occasion dress more feminine [but] there is that pressure of [having] to present myself in a certain way to even have a chance of being seen the way I want to.”

Getting misgendered also makes it difficult to focus on schoolwork. “[It] completely diverts my attention from what I was trying to do,” says Zelinsky Jobe. “Then that’s all I can think about throughout the rest of the class period.”

Overall, misgendering can have disastrous consequences for trans students’ mental health. “[Misgendering] can culminate into symptoms of depression, anxiety, body dysmorphia, and even Complex PTSD,” explains Courtenay Houk (she/they), an Associate Marriage and Family Therapist and SRHS Wellness Center Counselor.

According to the Trevor Project’s 2022 National Survey on LGBTQ Youth Mental Health, transgender and nonbinary youth with a gender-affirming school environment were 3% less likely to attempt suicide than those without. This past year, nearly 1 in 5 trans and nonbinary youth attempted suicide, while more than half seriously considered it.

When trans youth are at such a high risk, gender-affirming schools can be life-saving, but misgendering prevents this.

Of course, mistakes are inevitable. Stacey Farrell (she/her), a veteran SRHS teacher and the Gender Sexuality Alliance (GSA) advisor, explains that change is challenging, no matter how important it is.

“I think [pronouns are] something that, as teachers, we are still learning to incorporate into our routines,” Farrell says. “In the run of a class period […] it’s hard to keep all the things moving in the right direction. For me, that’s when it can get challenging or I can make mistakes.”

While she says it “sucks” to make mistakes, using the correct pronouns for students is something she prioritizes to create a “safe, inclusive classroom environment.”

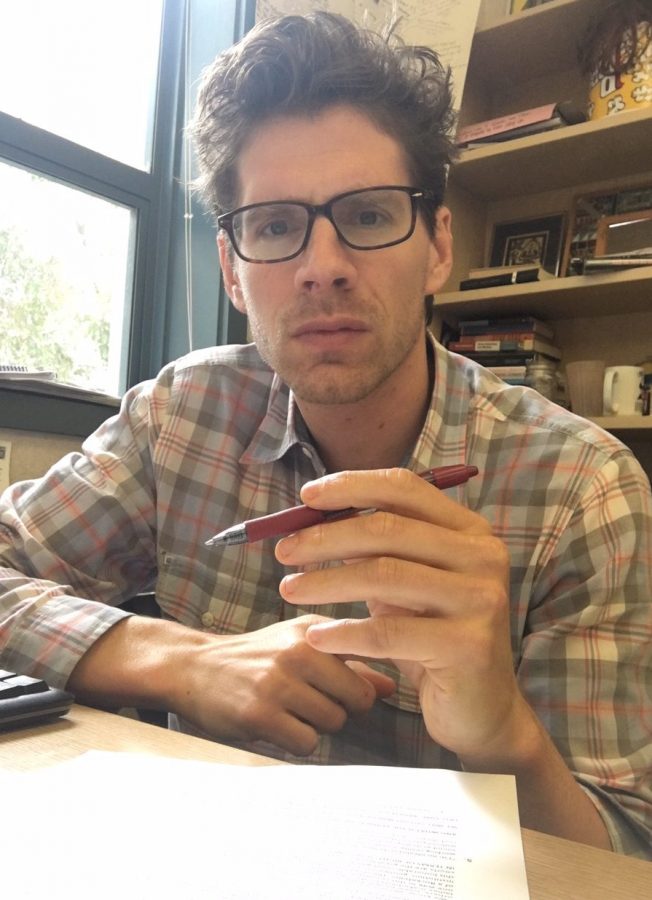

Jose Ortiz (he/him), another veteran SRHS teacher, recalls a recent situation where he misgendered a student. He felt awful and unsure of how to respond, but after apologizing, he began educating himself and working to be more inclusive.

“As a teacher, I need to be cognizant of the social atmosphere,” says Ortiz. “[Using the right pronouns is] really important, it’s just something new.”

Ultimately, though, situations like these are not the problem. It is when mistakes happen constantly, with no correction or improvement, that harm is done.

Tate recalls a now-retired teacher with whom he “historically” had issues. She frequently misgendered him, despite being consistently corrected. “Not only was it affecting me, it was also affecting how my peers perceived me,” says Tate. “It was uncomfortable.”

Goulding regularly must interact with a staff member who does not use his pronouns correctly. “If I correct them, they still just refuse to use my pronouns,” he says. “Even in the same conversation they’ll continue to misgender me.”

Situations like these are incredibly challenging for trans students to navigate, especially because trans people are stereotyped as being harsh and misunderstanding about misgendering. A friend even once told me he was scared to talk to trans people for fear of making a mistake and being yelled at.

People fail to understand that our anger does not stem from individuals, but from a lifetime of transgressions. The burden always falls on us to self-advocate. None of us want to be the “angry trans person,” because our anger is always met with defensiveness and frustration. We would rather give others the benefit of the doubt. However, it’s hard when we are misgendered repeatedly, with no improvement. How can we tell the difference between innocent mistakes and purposeful negligence?

Zelinsky Jobe hates correcting others about their pronouns publicly because they “don’t want to cause a scene.” They have experienced such adverse reactions, they often don’t even try anymore. Instead, they speak less in class to avoid getting misgendered.

“This is the least I have been perceived as a person in a school environment for quite a while,” they say. “I just don’t really talk to people anymore out of fear.”

This is exacerbated by the power dynamics between adults and students. “There is a major power imbalance between the teacher and the student that can make it very difficult to stand up for yourself,” says Goulding.

How can SRHS claim to be inclusive when our students fear speaking in class? How can we fly a rainbow flag when we do not fulfill the principles for which it stands?

The worst part is that misgendering is completely preventable. Navigating pronouns is a skill that can be easily learned, and there are countless resources to help, like simple how-to guides or comprehensive educator toolkits.

Last year, I spoke with a group of trans students at a staff meeting about all gender restrooms and supporting trans youth on campus. We asked teachers to use a survey at the start of the year to learn their students’ pronouns. None of the students I spoke to could report more than two of their teachers using such a survey this year. Our request was largely ignored.

Trans people are constantly asked to do emotional labor by educating others about our identities. However, we are tired of spoon feeding our stories to people who refuse to lift a finger for us in return.

I did not write this article as a call-out, but rather a wake-up call. The trans students of San Rafael High are done. We are done asking politely; done waiting for change that won’t come; done being disregarded and disrespected by this community.

San Rafael High, you have a pronoun problem. How will you solve it?

El Problema de los Pronombres: Por Qué no Podemos Seguir Malgenerizando a los Estudiantes Transgénero

“¿Ven lo que ella hizo allí?”

Las palabras de mi maestro me detienen en seco. Olvidé el problema que estaba resolviendo en la pizarra, sintiendo una vergüenza familiar. Me declaré como transgénero y comencé a usar el pronombre él hace más de un año, pero muchas personas todavía usan los pronombres incorrectos para mí, especialmente en la escuela. Lo enfrento todos los días, y no estoy solo.

La Escuela Secundaria de San Rafael tiene un problema con los pronombres.

“Estoy malgenerizado todos los días, varias veces al día,” dice estudiante de grado doce no binario Rai Zelinsky Jobe (they/elle). “Me hace sentir realmente ansiosa e incómoda.”

“Me hace sentir como una mierda. Realmente me desanima,” dice estudiante de grado doce transmasculino Jay Cates-Jackson (he/they/él/elle). “Trato de que no me moleste demasiado, pero algunos días sucede con mucha más frecuencia y no tengo idea de por qué.”

Estos estudiantes son transgénero, trans para abreviar, lo que significa que su identidad de género no está alineada con su sexo asignado al nacer. Las personas trans pueden ser binarias (hombre o mujer) o no binarias (cualquier identidad más allá del género binario). Si bien el lenguaje que se usa hoy para describir la identidad trans es un desarrollo reciente, las personas que no se ajustan al género han existido a lo largo de la historia.

Según un estudio de 2022 del Instituto Williams de la UCLA, el 1.93% de los jóvenes californianos de 13 a 17 años se identifican como trans. Por contexto, se estima que entre el 1 y el 2% de la población mundial es pelirroja, por lo que probablemente conozcas a tantas personas trans como pelirrojas.

A menudo, cuando las personas trans se declaran. cambian sus pronombres para expresar mejor su identidad. A medida que ha aumentado la visibilidad trans en la sociedad occidental dominante, los pronombres han entrado en el discurso popular a través de conversaciones sobre identidad y expresión de género.

Los pronombres comunes incluyen ella (she/her) o él (he/him) y el pronombre de género neutral elle (they/them). Muchos argumentan que el singular “they” (elle) en inglés es gramaticalmente incorrecto, pero en realidad se ha utilizado en el idioma inglés desde el siglo XIII. Otros pronombres neutrales al género en inglés incluyen neopronombres, como xe/xem o ze/zir.

Usar los pronombres correctos para alguien muestra afirmación y respeto por su identidad de género. Esto es especialmente impactante para los jóvenes trans.

“Si otros usan mis pronombres correctos, estoy gritando de alegría […] se lo digo a todos los que me rodean,” dice el estudiante de grado doce trans Conner Tate (he/him/él). “El listón está muy bajo.”

A medida que muchas instituciones trabajan para la inclusión trans, se alienta cada vez más a pedir y usar pronombres. Sin embargo, todavía se cometen errores a menudo. Usar los pronombres incorrectos para alguien se llama la malgenerización.

Las personas trans están malgenerizadas constantemente, ya sea sin querer o no. Es más comúnmente realizado por personas cisgénero (cis para abreviar) o aquellas cuya identidad de género se alinea con su sexo asignado al nacer.

Por ejemplo, Cates-Jackson está frecuentemente malgenerizado en la escuela, incluso por aquellos que no lo conocían antes de que saliera del clóset. Algunas personas incluso cometen errores sólo después de enterarse de que es trans. “Siento que necesito usar una etiqueta con mis pronombres para que la gente entienda más,” él dice.

Recientemente, Cates-Jackson estuvo malgenerizado entre un grupo de amigos, cuando un miembro del personal se refirió a ellos como “señoras.” Dice que la gente usa lenguaje de género como este “todo el tiempo.”

Zelinsky Jobe comparte esta experiencia. “No tienes que referirte a una habitación como niños y niñas o señoras y señores […] puedes decir simplemente todos o ustedes,” elle explica. “La gente es tan reacia a hacer cualquier pequeño cambio en su vocabulario.”

Por lo general, las personas que no conocen a Zelinsky Jobe asumen incorrectamente sus pronombres, pero incluso aquellos que lo conocen constantemente se equivocan, a pesar de los intentos de Zelinsky Jobe de corregirlos.

“Es molesto cuando la gente asume,” dice Zelinsky Jobe. “Podría usar un prendedor de they/them (elle), pero aun así, usé esos prendedores durante toda la escuela secundaria y rara vez funcionaban.”

La malgenerizacón perjudica la capacidad de los estudiantes trans para expresarse auténticamente en la escuela. “Realmente me gusta usar atuendos coloridos y brillantes [pero] eso se ve como un rasgo femenino,” explica el estudiante de grado décimo trans Jared Goulding (he/him/él). “Es que renuncio a mi sentido de la moda y todo lo que me gusta de mí o me misgenerizan”.

Tate está de acuerdo, “En ocasiones, me encanta vestirme más femenina [pero] existe la presión de [tener] que presentarme de cierta manera para tener la oportunidad de que me vean como quiero.”

Estar misgenerizado también hace que sea difícil concentrarse en el trabajo escolar. “[Esto] desvía completamente mi atención de lo que estaba tratando de hacer,” dice Zelinsky Jobe. “Entonces eso es todo en lo que puedo pensar durante el resto del período de clase.”

En general, la misgenerización puede tener consecuencias desastrosas para la salud mental de los estudiantes trans. “[La misgenerización] puede culminar en síntomas de depresión, ansiedad, dismorfia corporal, e incluso trastorno de estrés postraumático complejo,” explica Courtenay Houk (she/they/ella/elle), Terapeuta Asociada de Matrimonio y Familia y Consejera del Centro de Bienestar de SRHS.

Según la Encuesta Nacional de Salud Mental de Jóvenes LGBTQ de 2022 del Trevor Project, los jóvenes transgénero y no binarios con un entorno escolar que afirmaba el género tenían un 3% menos de probabilidades de intentar suicidarse que los que no lo tenían. El año pasado, casi 1 de cada 5 jóvenes trans y no binarios intentó suicidarse, mientras que más de la mitad lo consideró seriamente.

Cuando los jóvenes trans corren un riesgo tan alto, las escuelas que afirman el género pueden salvar vidas, pero la misgenerización lo impide.

Por supuesto, los errores son inevitables. Stacey Farrell (she/her/ella), maestra veterana de SRHS y asesora de la Alianza de Género y Sexualidad (GSA), explica que el cambio es un desafío, sin importar cuán importante sea.

“Creo que [los pronombres son] algo que, como maestros, todavía estamos aprendiendo a incorporar a nuestras rutinas,” dice Farrell. “En el transcurso de un período de clase […] es difícil mantener todas las cosas moviéndose en la dirección correcta. Para mí, ahí es cuando puede ser un desafío o puedo cometer errores.”

Si bien dice que “apesta” cometer errores, usar los pronombres correctos para los estudiantes es algo que prioriza para crear un “ambiente seguro e inclusivo en el aula.”

José Ortiz (he/him/él), otro maestro veterano de SRHS, recuerda una situación reciente en la que misgenerizó un estudiante. Se sintió muy mal e inseguro de cómo responder, pero después de disculparse, comenzó a educarse a sí mismo y a trabajar para ser más inclusivo.

“Como maestro, necesito ser consciente de la atmósfera social,” dice Ortiz. “[Usar los pronombres correctos es] realmente importante, es simplemente algo nuevo.”

Ultimately, though, situations like these are not the problem. It is when mistakes happen constantly, with no correction or improvement, that harm is done.

Por último, sin embargo, situaciones como estas no son el problema. Es cuando los errores ocurren constantemente, sin corrección ni mejora, cuando el daño está hecho.

Tate recuerda a un maestro ahora jubilado con quien “históricamente” tuvo problemas. Con frecuencia lo misgenerizaba, a pesar de ser corregida constantemente. “No solo me estaba afectando a mí, también estaba afectando cómo me percibían mis compañeros,” dice Tate. “Fue incómodo.”

Goulding tiene que interactuar regularmente con un miembro del personal que no usa sus pronombres correctamente. “Si lo corrijo, todavía se niega a usar mis pronombres,” él dice. “Incluso en la misma conversación, seguirán misgenerizándome.”

Situaciones como estas son increíblemente difíciles de manejar para los estudiantes trans, especialmente porque las personas trans son estereotipadas como duras e incomprensibles sobre el malentendido. Incluso un amigo me dijo una vez que tenía miedo de hablar con personas trans por miedo a cometer un error y que le gritaran.

La gente no entiende que nuestro enojo no proviene de individuos, sino de toda una vida de transgresiones. La carga siempre recae sobre nosotros para abogar por nosotros mismos. Ninguno de nosotros quiere ser la “persona trans enojada,” porque nuestro enojo siempre se encuentra a la defensiva y con frustración. Preferimos dar a otros el beneficio de la duda. Sin embargo, es difícil cuando nos malgenerizan repetidamente, sin ninguna mejora. ¿Cómo podemos saber la diferencia entre errores inocentes y negligencia intencional?

Zelinsky Jobe odia corregir a otros sobre sus pronombres públicamente porque “no quieren causar una escena.” Han experimentado tales reacciones adversas, a menudo ni siquiera lo intentan. En cambio, hablan menos en clase para evitar que se le misgenerizan.

“Esto es lo menos que se me ha percibido como persona en un entorno escolar durante bastante tiempo,” elle dicen. “Realmente ya no hablo con la gente por miedo.”

Esto se ve exacerbado por la dinámica de poder entre adultos y estudiantes. “Existe un gran desequilibrio de poder entre el maestro y el alumno que puede hacer que sea muy difícil defenderse,” dice Goulding.

¿Cómo puede SRHS afirmar ser inclusivo cuando nuestros estudiantes temen hablar en clase? ¿Cómo podemos enarbolar una bandera del arcoíris si no cumplimos con los principios que representa?

La peor parte es que la misgenerización es completamente prevenible. Navegar por los pronombres es una habilidad que se puede aprender fácilmente, y existen innumerables recursos para ayudar, como guías prácticas sencillas o kits de herramientas para educadores completos.

El año pasado, hablé con un grupo de estudiantes trans en una reunión de personal sobre los baños para todos los géneros y el apoyo a los jóvenes trans en el campus. Les pedimos a los maestros que usaran una encuesta al comienzo del año para conocer los pronombres de sus alumnos. Ninguno de los estudiantes con los que hablé pudo informar que más de dos de sus maestros usaron una encuesta de este tipo este año. Nuestra solicitud fue ignorada en gran medida.

A las personas trans se les pide constantemente que realicen un trabajo emocional al educar a otros sobre nuestras identidades. Sin embargo, estamos cansados de alimentar con cuchara nuestras historias a personas que se niegan a mover un dedo por nosotros a cambio.

No escribí este artículo como un llamado, sino como una llamada de despertar. Los alumnos trans de la Escuela Secundaria de San Rafael están acabados. Hemos terminado de preguntar cortésmente; cansado de esperar un cambio que no llegará; hecho siendo ignorado e irrespetado por esta comunidad.

La Escuela Secundaria de San Rafael, tienes un problema con los pronombres. ¿Cómo lo resolverás?

Jay Cates-Jackson • Dec 10, 2022 at 1:16 pm

This is real. Thank you for making those of us you interviewed feel heard!!!