Marin Transit Creates Division Among Bay Area Communities

December 10, 2022

Marin County, one of the richest regions in the US, suffers from a significant gap in transportation. The Bay Area consists of nine counties, but the Marin transportation system is one of the only ones that does not provide service to the East Bay.

Due to lack of transportation, those who travel to the East bay from Marin do not have the option to take a train, or even a bus. The only way to get to the East Bay through public transport is to go through San Francisco, meaning if you live in Marin, you have to ride the bus or take the ferry to S.F., and take a second bus to the East Bay. This is unacceptable as one of California’s most powerful and wealthy counties.

Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART) for example, has been operating since 1972 while the SMART Train (Sonoma Marin Area Transit) only opened in 2017. The fact that the SMART Train only recently added a transportation system within Marin shows how far behind we are.

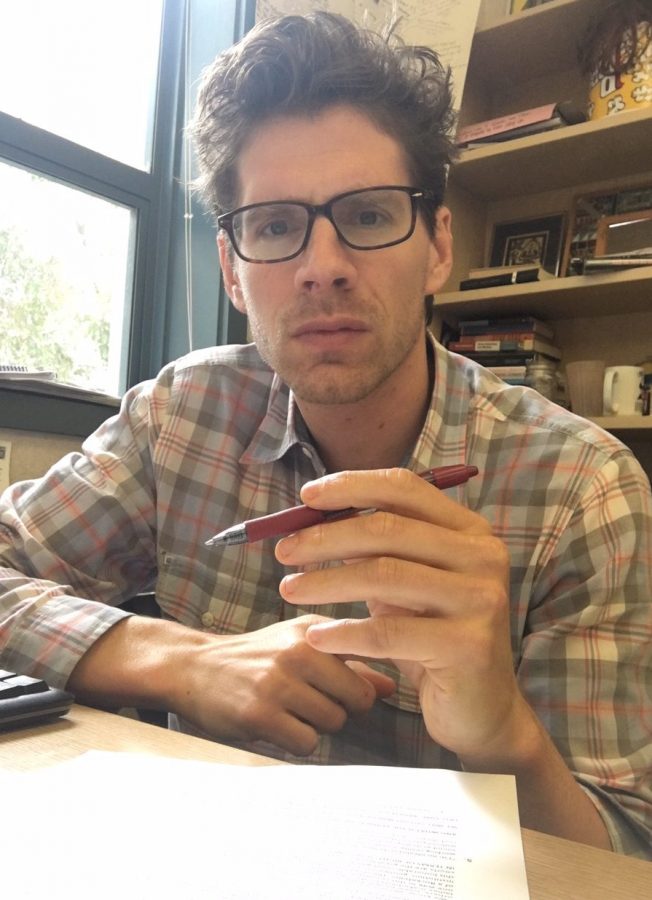

Comparing Marin’s SMART Train with BART speaks for itself; BART has many stops in San Francisco, Concord, Daly City, Richmond, and Fremont including all the cities in between. SMART Train travels to five zones between Sonoma and Larkspur. It does not reach any of the larger urban hubs, and has limited connections or links to other forms of public transportation. Mr. Allen, a history teacher who has lived in Richmond his entire life, says, “It caters to very few people.”

An East Bay resident and student attending University of Berkeley, Bianca Maccabi, related the problems of getting to Marin County and back via public transportation. “I have to coordinate a lot just to visit my family’s home in San Rafael because I can’t just hop on a bus; I have to either rely on a ride from someone or pay for a $50.00 Uber,” she said. She feels that it is intentional the way that transportation divides communities. “It’s very easy to get around within the East Bay, and it’s actually really easy to get to SF, but when you’re trying to go North, that’s the problem.”

Maccabi was quick to point out that there is nothing connecting the North, East, and South parts of the Bay Area so that the public can move within the communities with ease, which she thinks is another example of the division of transportation among groups in different counties. Allen also noted that, “The lack of transportation in certain areas ensures people who don’t have automobiles don’t have access to some of the wealthier neighborhoods.

Despite having the SMART Train, Maccabi feels that the traffic in Marin has not improved since its opening and instead has gotten worse. The point of the SMART train seems to have been defeated because there is still so much congestion in downtown San Rafael.

Maccabi further added it is expected that the people of Marin County have cars because of their extreme wealth, “Marin County does not spend on transportation that connects to the East Bay; this contributes to the inequity of the socially and economically diverse areas of the Bay. The little communities within the Bay Area without transit connections creates a sense of isolation. Even though one can get to Marin from the East Bay through San Francisco by bus, it is time consuming and impractical.”

When you step back from the transit situation in Marin compared to other transit systems in the Bay Area, you might also wonder if Marin County is shutting out minorities and marginalized communities. There is no bus, train, or ferry that connects East Bay neighborhoods to anywhere in Marin. So, commuters from the East Bay have two choices: Drive a car across the Richmond/San Rafael Bridge or take a bus through San Francisco.

Mr. Allen spoke about the traffic and commuting time. “On average, it can take between 45-70 minutes to get to or from the East Bay,” he said. “The first thing I do when I wake up is to check the traffic. I check it three or four times before leaving.”

Allen went on to say that the new bike lanes (circa 2019) going across the Richmond Bridge has created fewer car lanes and that it is underutilized; it has made bridge traffic worse. The other issue is that it is so expensive to live in Marin and that a majority of people who work here live outside of the county, forcing them to commute. He believes that about 50% of the cars he drives past are work vehicles servicing Marin. However, Allen notes that the third lane on the upper deck of the Richmond Bridge going home has been a game changer (circa 2018) cutting his drive home in half. The downside is that the third lane does not benefit East Bay commuters attempting to get into Marin.

Allen added, “In the morning the traffic is backed up in the exact same way in the East Bay, and no one seems to care. In addition, there are no plans to have another lane come this way because people seem to love the bike lane that nobody uses.” Allen shared his overall feelings about the transit issue; “It’s an issue without a solution. I think we are just stuck with it, and it’s definitely not an accident that it’s the way everything was set up.”

Outside of Marin, diverse communities become even more segregated. Isolating diverse communities coming and going to Marin is a consequence of Marin’s lack of awareness, and government/state spending on public transportation. This puts other people attempting to come into Marin in a place of imposition with the time and money it would take to get to Marin and back.

Here, it’s a privilege to go anywhere without inconveniences other counties face. Maybe it’s time to pop our own bubble and start connecting more, especially to the East Bay.