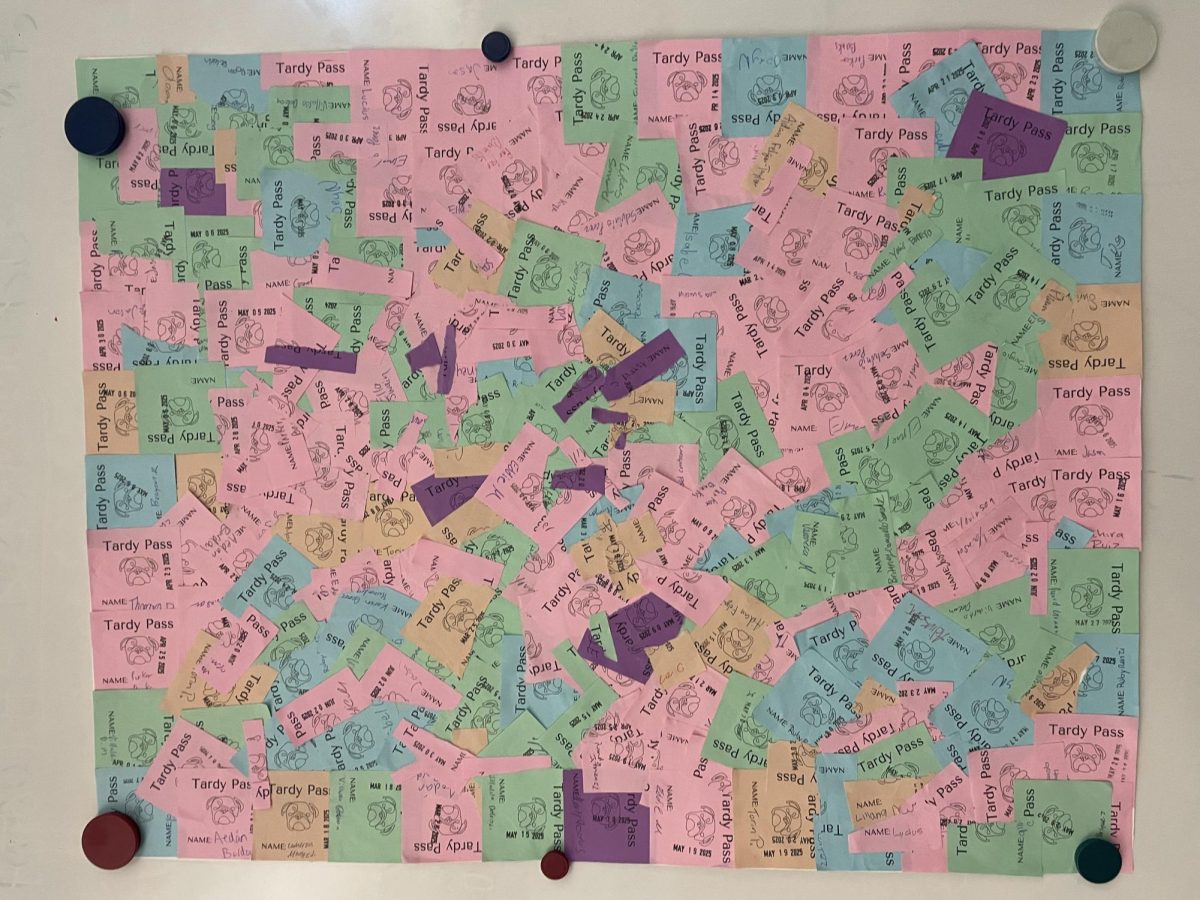

Standing tall over the SRHS campus is over sixteen million dollars worth of steel, glass, and fabrication equipment. This new STEAM building is home to the Academy of Engineering and Technology (AET), a program that offers opportunities for students to get hands-on experience in a state-of-the-art fabrication lab complete with a 3-D printer, laser cutter, CNC router and lathe, and multitudes of other tools available to the class. AET prepares students for possible career paths into engineering and physics by completing projects that utilize valuable skills and knowledge, including robotics, CAD design software, and woodworking. However, if you take a closer look at the demographics of the classes, it’s obvious there is a huge imbalance. The amount of female students enrolled in AET is significantly lower than that of their male peers.

“I try to treat all of my students equally when it comes to the high standards of AET, but I do have to realize that these female students are working in an environment that is not traditionally designed for them, and they know it,” says AET physics teacher Sabrina Paiz. “All I feel like I can do is make sure that the students feel comfortable, and respected, and that they know that they belong in this program.”

This is not an uncommon situation across schools nationally and internationally. This imbalance is evidently the reason women, although half the population, make up less than a third of the STEM workforce. The pipeline of female high schoolers in STEM classes to female STEM workers is incredibly weak. Women need to be involved in STEM because they increase diversity, offer fresh perspectives, and create a more inclusive culture in the workplace— and they are good at it. Science and technology are actively seeking to improve society, and it’s crucial that women have a place in the future of innovation.

Active encouragement from teachers is the key to increasing the width of this pipeline. Even if teachers are not necessarily against getting more girls into STEM, it’s not enough to remain neutral. Specific outreaches from teachers to female students will inspire them to broaden their horizons into the STEM field because they will feel seen and valued.

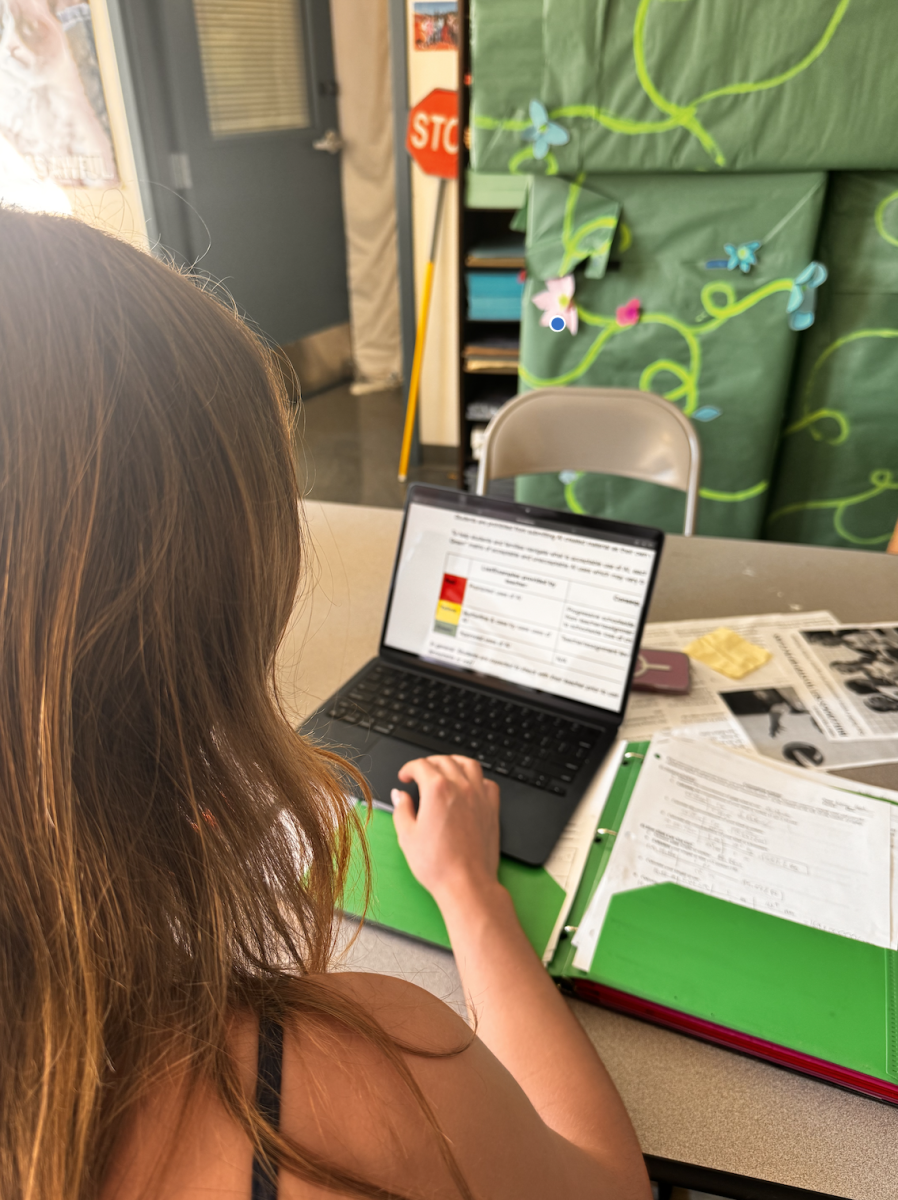

Based on my own experience of being female in STEM, girls encounter roadblocks that make it difficult to want to pursue something that doesn’t seem fitted to them. One of these roadblocks is called the imposter syndrome: a feeling of intellectual self-doubt, as if the individual is not worthy to be where they are. While it’s possible for both men and women to experience this self-sabotage, it’s much more common for women. Being a minority shines a spotlight on you: people expect more from you to prove your legitimacy. This often translates into feeling that anything below perfect and flawless is not good enough.

“Usually, the females we get in the academy are top-of-the-class students who dive into the material and tackle it better than their male peers,” says Paiz. “But the confidence they express in their understanding does not match their determination.”

A study done in 2017 by Microsoft found that 21% of high school girls feel embarrassed to ask for help in their STEM classes because they think they’re the only ones who don’t understand the material. This tendency was found to be more common among girls who weren’t encouraged by teachers. This is proof of the imposter syndrome creating a fixed mindset. Placing an emphasis on learning from mistakes rather than getting everything right the first time teaches students to think with a growth mindset. Teachers need to make it clear that hard work and determination is how you expand your knowledge so girls can transform their mindset into a more positive and forward-thinking one.

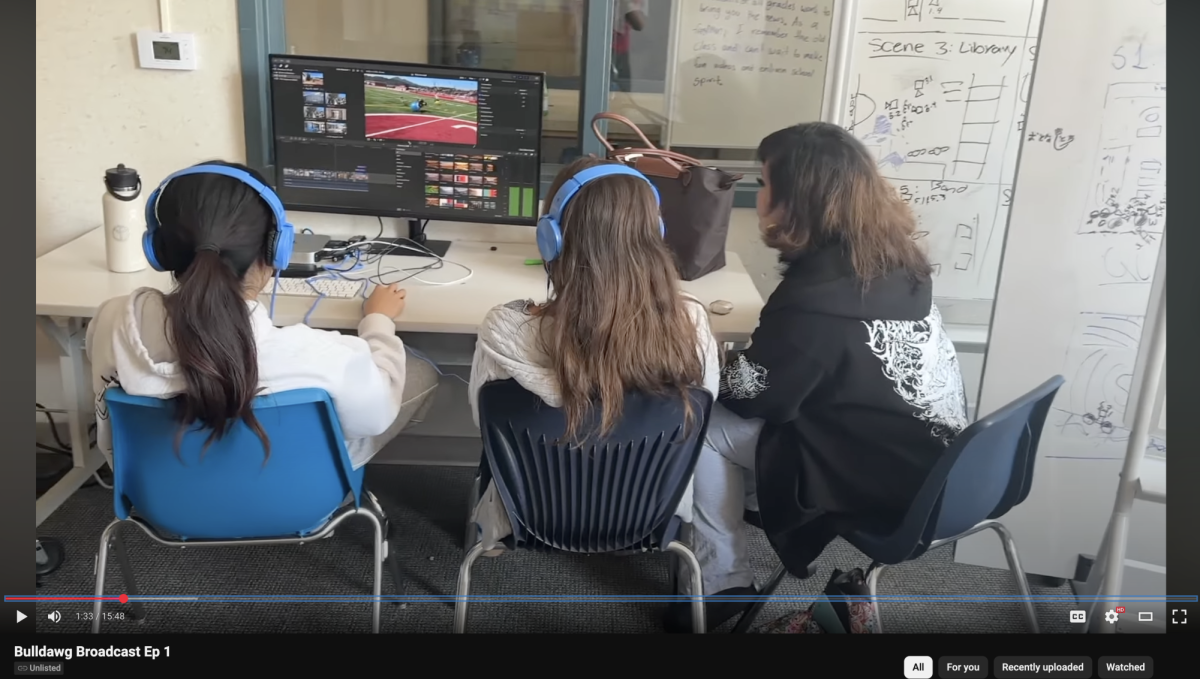

Outreach from teachers needs to have a solutions-oriented approach. For example, SRHS could offer tours of the STEAM building to middle schoolers and get those students, especially young girls, excited about all the possibilities in AET. Or, the school could send girls to national conferences about women in STEM to inspire and show what the future could hold for them.

Administration could also heavily promote after school programs or clubs and teachers seek out and directly urge girls to join the clubs. According to the National Girls Collaborative Project, 70% of girls who participated in a science-focused program outside of school learned new skills and had fun, and 90% of girls said that their interest in science increased. Teachers need to directly and specifically incentivize girls to at least try out these programs to open their minds to the expansiveness of the STEM field.

Some may say that girls are naturally less interested in pursuing STEM; it’s completely their choice whether to go into the field or not. However, although girls may not seem to be interested in STEM when they’re older, this is due to gender biases embedded in their subconsciousness. From a really early age, young children notice and absorb gender roles in the world around them. It’s no secret that the majority of scientists are portrayed as men in the media.

A research article published by Sage Journals in 2016 says that STEM career guides state that “success in science primarily relates to such characteristics as intelligence, hard work, rigor, persistence, motivation to achieve, assertiveness, and the ability to solve problems,” which are generally considered more masculine traits, according to the article. Educators have the ability to help reverse the effects of societal stereotyping by taking action to invigorate and integrate girls into STEM. Instead of allowing them to feel stranded, motivating and heavily encouraging female students will make them understand that they possess all the qualities of a successful scientist and more.

When I was in 6th grade science class, there was a homework assignment to draw what we think a scientist looks like. Originally, I drew a male scientist. But after showing my parents my work, my dad asked me, “why didn’t you draw a girl?” At the moment, I honestly didn’t know, but I redrew and changed it to a female scientist. The next day in class, only 3 drawings were female, all of which were drawn by girls. The rest of the class of about 30 students drew a male scientist. The idea that science is for men begins this early, if not earlier, whether the child is aware of this stereotype or not. This harmless activity reveals the undercurrents of societal standards through a child’s eyes.

According to Microsoft, “when asked to describe a typical scientist, engineer, mathematician, or computer programmer, 30 percent of girls say that they envision a man in these roles. As do almost 40 percent of adult women—and 43 percent of women in STEM and tech fields.”

These statistics are not set in stone and can be changed as long as teachers are not neutral about increasing the number of girls in STEM classes and activities. Wanting equality in the classroom is not the same as demanding it and making it a reality. Why not actively push to build classes that reflect a broader population? This is an issue that cannot wait any longer: the sooner educators strive for classroom diversity, the sooner the effects gain traction and increase the pipeline of girls in STEM classes to women in STEM careers. From there, who knows where the future will take us?

José Ortiz • Jan 17, 2024 at 11:44 am

Thank you for your important insight. I agree, we can do more to diversify the high school science classroom.