SECTION I: THE FORMATION OF THE BOX

“I don’t think art will ever go away. It’s been around longer than anything. Humanity started with early cave dwellers scribbling on the walls. You need to have an outlet for everything,” said San Rafael High School teacher Ms. Kury.

Kury has been proven right by students, teachers, and creators worldwide who do the necessary work of keeping the arts relevant, valued, and inspired. But you wouldn’t necessarily know this from public school funding or what students have been taught to prioritize and value.

United States schools often settle into an educational model that is driven by the desire to churn out productive citizens who are capable of bolstering the economy and entering the job market with the right qualifications. However, this system fails to account for the innate human tendency to create, express, and play. Without art and creativity incorporated into schools and society, we fall out of touch with an entire half of ourselves. No empire or culture has ever outlived its art— consider the reputations of periods like Ancient Greece and Egypt, the Renaissance, and even the late 1960s. In the current day, as science and technology grow and seem to double in bandwidth every year, art has never been more critical.

“Art is what makes us human,” said Zane Fiandaca-Olsen, SRHS artist. Fiandaca-Olsen, whose favorite medium is drawing, has been doing art since he was in elementary school. He finds great peace in expressing himself through art.

Jennifer Jackson is a senior at San Rafael whose work includes drawing, painting, and digital art. “In terms of how my head works- it’s more logical, but artwork allows people to explore their emotional side,” she said. She’s found a way to combine these two sides by doing digital art commissions, turning her creations into a business.

While plenty of students might not see themselves as creative people, and instead would prefer to, for example, write an analysis, creativity can percolate in other ways. While it’s true that not everyone channels creativity into artistic outlets, knowledge and involvement with the arts is valuable. Out-of-the-box thinking can translate to invention, problem solving, aesthetic understanding, and people skills.

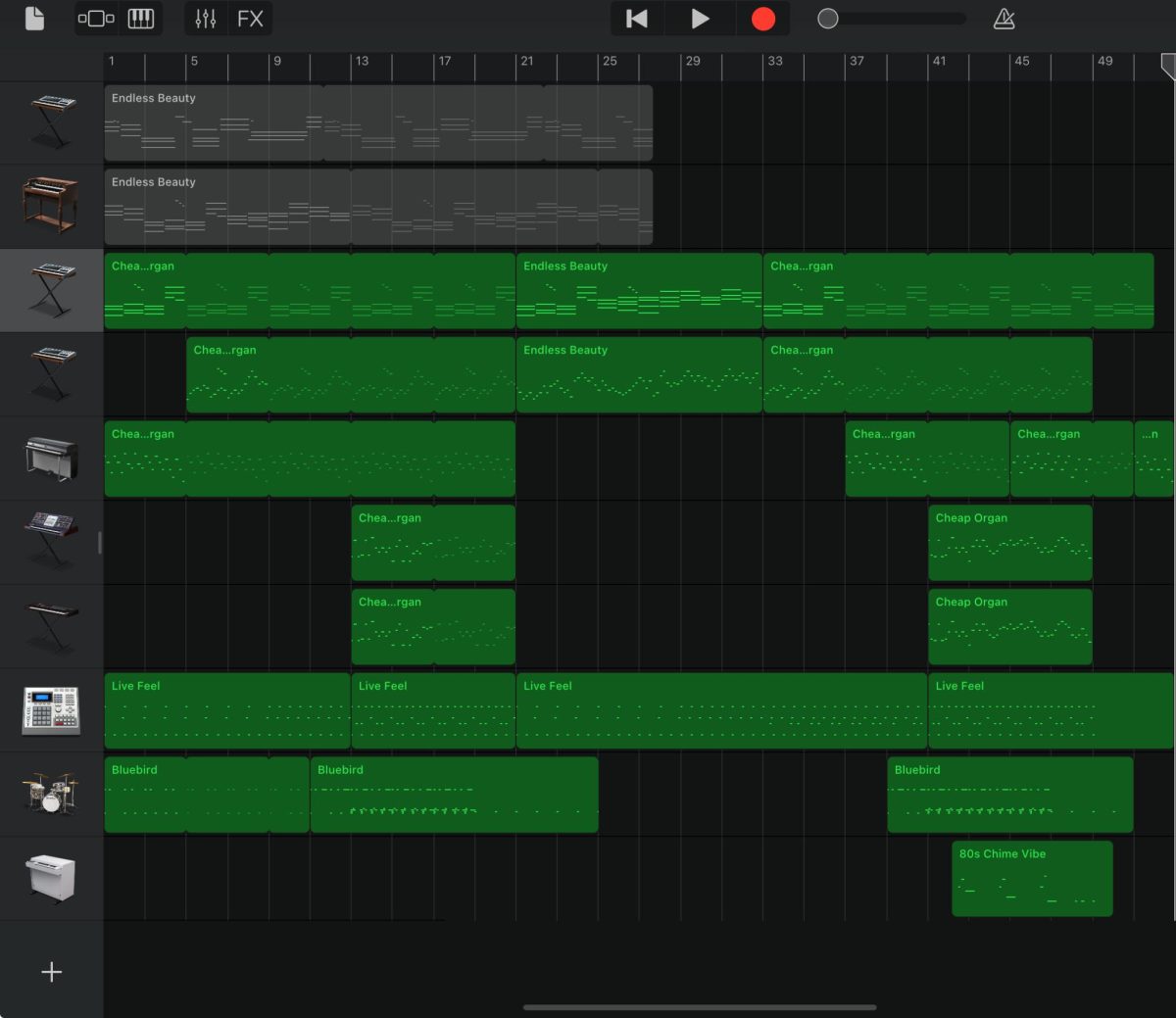

SRHS music teacher Mr. Burdick says that one thing musicians in particular do quite well is “setting a goal and then learning how to break it down into pieces and going after each one of those pieces individually so that they can then make the goal a reality afterwards.” Although goal setting does not come across as a “creative trait,” it is something that shows up more frequently in kids who are involved in the arts and music. Coincidence? Mr. Burdick thinks not.

According to an article published by Fortune this year, liberal arts backgrounds have become desirable in professions that traditionally prioritize analytics. This is because, as Ms. Kury says, “people are always trying to take away or diminish the humanities courses- and you need them to be a functioning human being.” The humanities enrichen and add depth to seemingly unrelated fields. In a world where technology is raising the bar for where human talent and creativity is merited, the arts will surely be one of the last things to remain after robots take over science and mathematics.

In higher education, majors in the arts are plummeting. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics shows a drastic decline in the number of graduates in the humanities of 29.6% from 2012 to 2020. This is partially a result of colleges prioritizing specialization over core curriculum— which often includes the liberal arts. The idea of concentrating expertise into a certain field makes a lot of sense— it prepares students for industry success and to become professionals in their forte. However, if students are forced to choose between either a high-paying STEM major or a major in the arts which does not guarantee a job, the choice is obvious. This pattern of science and tech sovereignty reflects not only a change in collegiate approaches, but a difference in the way the arts are being marketed towards students from a young age, and a shift of societal paradigms.

Perhaps this change in values can be traced back to the introduction of the factory model of education, conceptualized by Horace Mann in 1843. Having grown up in an area bound by religious tension, he sought to eliminate the direct influence of political ideologies on students. His goal was to create accessible public education for all, meaning that the model of education that is so heavily criticized today was created with pure intentions.

According to Dr. Katie Lewis, who is co-chair of the education department at Dominican University in San Rafael, the main goal of K-12 education has been to create productive citizens primed for the workforce. “That’s not a great way to conceptualize a public education,” she said. Instead, her philosophy is that from kindergarten through college, the focus should be to become well-rounded and think critically across all aspects of our lives.

Mann’s model did accomplish its goal: the students raised through the factory model of education were a more homogeneous and tolerant group better equipped for the workforce. But it presented an issue: working with a system that pushes unity and conformity, how are teachers supposed to bring out students’ natural creativity? Teachers at San Rafael High are finding ways. Programs at schools are growing, despite the influence of a job market which does not call for degrees in the humanities.

Money has a tendency to flow towards sectors that are already lucrative. Considering the fact that American society values productivity, optimization, and industry above all as a means to establish ourselves as global leaders, investment in science and tech is just the logical conclusion. State investment follows profit, which follows societal values.

The state of California has allocated some money towards arts and music programs. Proposition 98 was passed in 1988 and establishes a baseline amount of funding that must be granted to education. 34 years later, in 2022, Proposition 28 was signed into law and designated 1% of prop 98 funding to the arts and music programs.

Despite this, Mr. Temple acknowledges the gap between science and art funding. While AET and the SRHS construction program receive around 30K a year (this is Perkins funding, which goes towards every CTE (career technical education) program in the USA), he has not received arts funding in a long time.

This doesn’t come as a surprise— science equipment is very expensive. The SRHS engineering program has to find a way to pay for expensive 3D printers and saws and fund projects for hundreds of students. However, music programs do have an equivalent: many of the instruments cost thousands of dollars. A mid-level Tuba costs about $6000, a set of Timpani costs around $15,000, and a marimba is around $8000. “Our instruments hold their value longer than the average piece of tech equipment, because they don’t go obsolete, and there’s often no budget planned for their replacement in many districts,” said Mr. Burdick. Thankfully, SRHS Music has supportive boosters helping to cover these costs.

Funding the arts can feel forced and therefore often relies on community organizations. Ms. Kury is a relatively new teacher at SR who has experience at both private and public schools.“As far as funding goes, I think it depends on the environment… the pool is a lot smaller in public schools, but you have these parent run organizations like the boosters that help fill the gap between the two,” she says. SRHS boosters declined to comment.

“What I’m learning about is that you need a community to be involved to have the humanities thrive,” said Ms. Kury.

SECTION II: PRESSING ON THE WALLS

Mr. Burdick is the teacher of the flourishing San Rafael music program, which is currently coming off of five first place wins at the Music in the Parks festival in American Canyon. After growing up surrounded by music, Mr. Burdick wanted to bring the close-knit familial feeling of his own band programs to San Rafael, which he has been doing for 18 years now. Though COVID dealt a blow to the music program, Mr. Burdick says that “there will always be kids that are passionate about music, it just sometimes takes some time.”

Mr. Burdick compared the role of teaching music to that of teaching higher level math. Schools teach students higher level math, despite the fact that the majority will not become physicists or professional mathematicians— because they are trying to teach kids how to think. “Music has all those same things, and it also has that socioemotional component which is really important for people to learn how to function emotionally,” he said.

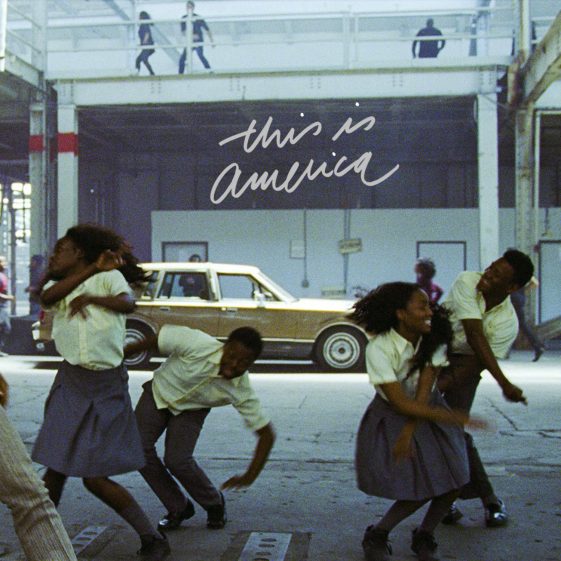

Emotionally, music communicates things in a way that words can’t, echoing what Ms. Kury has said about art: “When kids are able to express themselves through movement, sound, song, and visually, it provides an outlet that’s much easier to access when you can’t find the words and are still developing as a human being.” Both teachers said that in an age where connection has become a commodity, art and music bring people not only closer to themselves but closer to others around them.

“As we become more and more embedded in tech as a society, there is a yearning for something more down to earth, craft, organic,” said Mr. Temple. He comes from a conjunction of interests in physics, computer science, illustration, graphic design, and furniture making— all of which combine aspects of science and art. Mr. Temple channels his skills into making custom furniture and loves the feeling that accompanies it.

“Oh wow, that was made by a human. It’s got that feel to it. That’s why I like making furniture—it’s something you can’t buy at Target. I made that, it’s unique, nobody else has a kitchen table like that. It has my own personal touch,” he said. Mr. Temple seems to put his personal touch on a lot of things. He was one of the founding fathers of the Academy of Engineering and Technology at SR and also runs Media Academy, a program that teaches students to shoot, edit, and produce films.

Mr. Temple talks a lot about what he describes as “the interplay between science, which is a language of nature, and how that sort of understanding can be used to enrich our artistic reactions.” In other words, if we look at science as the language of nature and art as the language of humanity, it becomes clear that they are complementary points of view, as opposed to two sectors competing for funding and attention. By extension, art and nature are complementary. Mr. Temple also told me that he likes to incorporate his experiences with nature into his artwork, as someone who also loves the outdoors. Zane Fiandaca-Olsen and Kelsey McNair, artists at SR, both often look to nature for ideas. McNair’s observational method of choice is going on wildlife drives nearby, as Marin county is known for its biodiversity and wide range of habitats.

McNair is a senior at SRHS who channels herself into functional ceramic art. Often inspired by nature, her time at the wheel manifests as unique mugs, plates, and bowls, though she’s currently working on a landscape piece inspired by the way rain strikes the ground. McNair is in her second year with SRHS ceramics.

“I’m honestly terrible at art- I can’t draw. But with the clay- it can be anything. It can be messed up and changed,” she said. The malleable nature of ceramic art helps her understand and work with not only nature and beauty, but also people and emotions. As a creative person who also is diagnosed with bipolar disorder, she said she often struggles in conventional classes, which don’t usually capitalize on the hands-on approach of an art class.

Art has given her a reason to come to school and something to look forward to when she has to sit on screens for the rest of the day. She’s planning on continuing her creative career at Orange Coast College in Costa Mesa, California, where she will be playing softball and spending even more time at the pottery wheel.

“All of my perception is way heightened, everything is times 100… so when I’m in classes that can accommodate the way I learn, it’s really helpful,” said McNair.

SECTION III: ESCAPING THE BOX

Dr. Katie Lewis began her career during the passage of the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB). In her mind, that was the beginning of the end. NCLB aimed to elevate the academic performance of students living in poverty, English second language students, and students in special ed. It held schools accountable for low performance, and rewarded high standardized test scores, and was in place until it was overturned in 2015 because of its flaws.

As a result of NCLB, the focus on standardized tests became immense. “You have to do well on these tests or you will lose your funding,” was the idea, according to Dr. Lewis. These tests measured math and ELA, putting those subjects into the spotlight and casting the arts and history to the side. Though educators tried their best to still teach the humanities, it was difficult due to the fact that the curriculum just did not incorporate them.

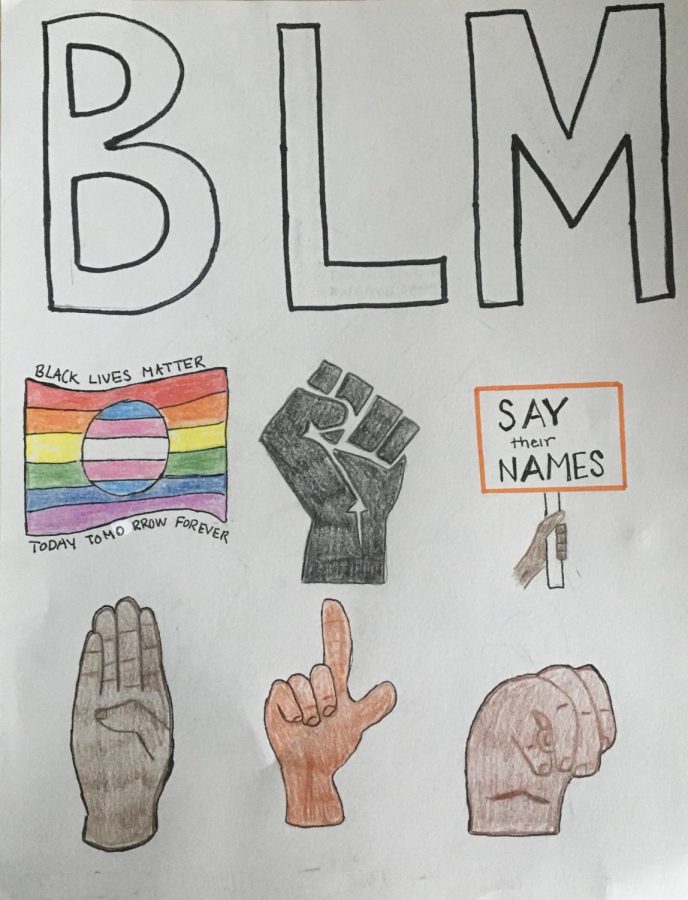

Dr. Lewis currently teaches visual and performing arts, while also helping people earn their K-12 teaching credentials. On top of all this, she teaches social justice and equity. Before getting hired at Dominican, Dr. Lewis taught in elementary schools, which gave her a new perspective on the arts in schools. She worked at a school that had special education students included in classes with the rest of the school, giving her a firsthand view on the benefits of visual and performing arts.

Growing up, she did not have access to arts programs because they were only available to higher socioeconomic demographics. Despite this, she taught herself to play piano, guitar, and flute, eventually developing an interest in graphic design. Majoring in design, she struggled with the fact that her creativity was restrained by what people wanted her to create.

“There’s a pressure to make art commodifiable- that capitalism pressure- and it made me feel like I had to do graphic design to make money and survive. But the reality of that world is that you don’t get to express your creative side, because you have to follow the vision of the customer,” she explained.

Though American schools eventually shifted away from the factory model and its rote memorization, strict discipline, and passive approach, 21st-century education was still drawn from its blueprint. Current curriculums and teaching styles focus instead on critical thinking and collaboration to better prepare students for higher education and jobs. However, so much is still up in the air when it comes to the message education is sending about the arts. It brings to mind questions such as: What is the measure of success? What makes an education a good education?

The answer, according to Fritzjof Capra, author of The Turning Point, is balance. The Turning Point connects the major problems of our time to changing dynamics in worldview. Capra references work done by sociologist Pitirim Sorokin in 1941 which explains a waxing and waning pattern of three value systems: the sensate, ideational, and idealistic. The sensate value system places emphasis on using sensory perception, and only sensory perception, to discover truth. Meanwhile, the ideational system believes that “true reality lies beyond the material world, in the spiritual realm, and that knowledge can be obtained through inner experience.” (Capra, 31). The ideational system is exemplified in both Western and Eastern religion, including Christianity, Judaism, Hinduism, and Buddhism.

Sorokin philosophized that over time, these two schools of thought interplay and gain and lose power, and that in between the two is an idealistic stage. The idealistic stage is based on the fundamental idea that the sensory and the spiritual coexist and build upon one another.

According to Sorokin, since the Industrial Revolution, human society and culture has entered a turning point: a transitional phase between these two ideologies. Examples of other transitional periods are the rise of Christianity at the fall of the Roman Empire, the transition from the Middle ages to the Scientific Age, and the invention of agriculture. He attributes the cause of this “turning point” to changes in mathematics and physics which shifted the way that we view nature.

Because of Descartes and his view of nature and physics, science began to view nature less as an organism that we were one with and more as a purposeless machine to be exploited at will. This mechanistic worldview upset the balance between two systems.

According to The Turning Point, the sensate and ideational systems can be associated with the Chinese concept of Yin and Yang— two forces which strive to equilibrate. The sensate, along with the yang, represents the masculine, expansive, demanding, aggressive, competitive, rational, and the analytic. The ideational and the yin correspond with feminine, contractive, conservative, responsive, cooperative, intuitive, synthesizing ideals.

With the Cartesian worldview came a new emphasis on the yang. Rational knowledge trumped intuition, competition was valued over cooperation, science is seen as more important than religion, and along with these ideas also came the reinforcement of the patriarchy. These social currents provide an explanation for why our society seems “sick” and out of whack. And they are also the reason why we are losing touch with the arts.

The “yin” values— the intuitive, nurturing, creative side of us— have become associated with lower-paying jobs such as caretakers, artists, musicians, and mothers. Additionally, the continuous growth of mass-production and a “quantity over quality” mindset has fed the yang, to the point where it has affected the way that we treat the poor and ill, the characteristics we value in our children and partners (which has in turn created a mental health epidemic), and almost every other facet of culture.

Taking into the account that we are currently experiencing one of the largest turning points in human society, it comes as no surprise that our ethics and values are in discord, and that this translates to the humanities. The humanities are associated with the ideational system of thought and with the yin, and we do not grow up learning that these things are important.

It follows that practicing and understanding the arts restores balance to a person who has grown up learning that rational thought is the sole important thing. It teaches us emotional intelligence. It connects us to other people. Most of all, it brings out part of human nature that has been repressed. Thomas Gilmore, professor of politics and economics at Ave Maria University in Ave Maria, Florida, has said that “the liberal arts should not be squashed by the monotony of servile work and office life, but rather they can be the gateway to joyful and meaningful lives in this restless and despairing society.”

Capra’s main ideology is the Systems View of Life, the idea that all of the problems of our time are connected and come from a common origin. Combined with Sorokin’s theory about the fluctuation of our values, it seems like art might have an imminent return.

“Maybe art will have a renaissance,” said Mr. Temple.