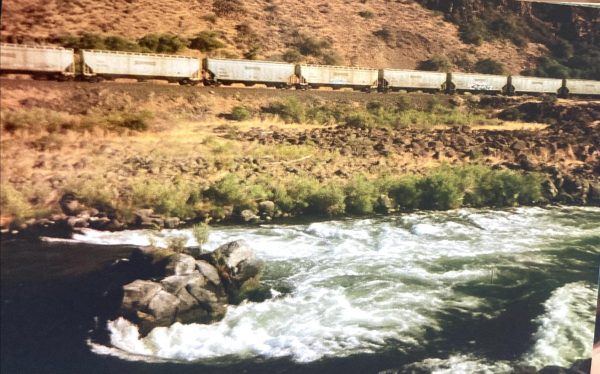

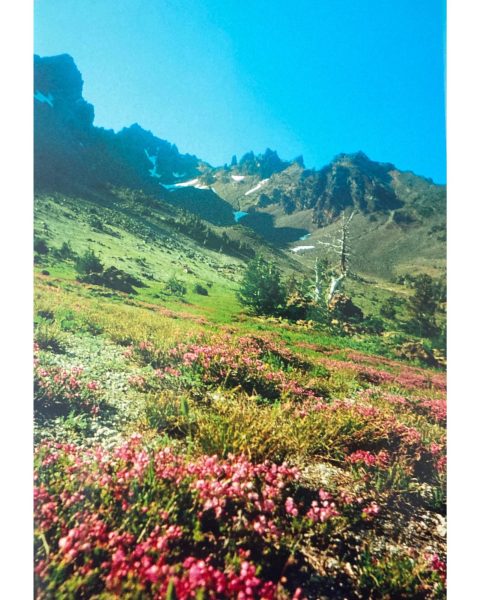

The Deschutes River runs through the middle of Oregon, bending between fields, forest, desert, and ravines, catching the light of the sun rising in the east. Every turning point in the river reveals fresh sights. No segment is the same.

The turning point for my life happened on the Deschutes, and on its banks, in the summer of 2021, after my freshman year. Most people go into Outward Bound looking for something transformational- why come here if not to change?

The city sounds faded as the ten of us strangers hiked into a battle with the elements, knowing we would lose. Through hips blackened by the weight of my pack and wildfire wind that reminded me all too well of the 2018 fires that burned down my grandparents’ home, I learned how to meet these kids and how to understand them. We’d sit after dark filling in the circle with stories under a milk-stained sky, wake up before light and rise to go. And we’d just walk. Leather boots, Vibram soles bruising the ground we touched.

The trip was two full weeks, one backpacking in the mountains, the other rafting on the river. I was, for one of the first times in my life, out of my comfort zone. With a 70 lb. ill-fitted pack cutting into my shoulders each

day for each of the 6-9 miles, I was quickly exhausted. By the end of the backpacking, I could not have been more ready to cruise down the river. Once we were on the water, the primary emotion I felt was elation. Falling down class 4 rapids sure does bring a group of people together like nothing else.

One member of our group, Sawyer, was attempting Outward Bound for the second time. Crippled by anxiety, bipolar disorder, and PTSD, he had given up and gone home a year earlier. He had embarked on this trip with his best friend, aiming for the mark of completion. He was a cool kid— you could tell just by talking to him. He made you laugh. He had noticeably pale skin, moonlike. Stood 5’9 and lanky, birthday December 12. Grew up in the Sunset district on a street I still pass a couple times a month on the way to see friends. He observed the world through big blue eyes, smiled rarely with straight white teeth. He loved philosophy and LSD to the point where we would beg him to shut up about it. Sewed before men did that, made beats, skated before it was cool. And he told us how he’d been to juvie and why he was mostly vegan and how his parents had divorced. How the only person he could see himself with was a girl who was leaving for college. He said all this like he’d never told anyone anything before, like Oregon was the first thing to make him open.

I could tell from the jump that Sawyer and his best friend Owen were sending each other into a spiral. They were two kids, one with bad mental health and the other with horrible mental health. One night, Salma and I walked with Owen to the ridge to watch the sunset. Around an hour into the conversation, Owen revealed that he had bit the skin down on his finger, deep, til he hit tissue. That’s when I realized just how much he had been struggling over the course of the trip. All the times he and Sawyer had split off from the

group, the times he lagged behind while we backpacked, the times that he had stayed quiet for an entire dinner— he was lost. I suspected it early on the trip when he lay down flat on his back, dizzy, in the middle of the circle, scared by the stars. And I knew it for a fact when, 1 week into the 2 week trip, Sawyer and Owen told us that they were leaving early and “couldn’t do it anymore.” It changed me to see them leave because they couldn’t live without drugs and distractions, even if it was in the best place on Earth with good people who had the best of hearts.

The night before they left, they told us everything. We were lost and dizzy looking at stars as two introvert boys from San Francisco, too hurt to remain by the river, told us why. But it wasn’t what they said that changed me the most- it was how Salma reacted.

She was a year older than me, with curly brown hair, from Berkeley. Her name meant ‘peace’ in Arabic, but white. She was pretty ordinary except for the fact that her talent was listening. She could pick up on the slightest change in someone’s demeanor and tell you why. She remembered the birthdays of every friend she had ever had. She liked to laugh and ran a radio station, where she was nicknamed “Salma Listened.” And she sure did. When Owen told her all the things that had happened, she hugged him and held on for what must have been ten minutes. He did something nobody would have expected: he told her, “That just, I don’t know, reached me.” She said, “I know.”

After that we watched the fire until it flamed down to embers. I wasn’t thinking about it too much then, but I realize now that that night was when I learned how to listen.

***

I was taught to read at a young age. When I arrived at kindergarten, my teachers and parents discovered that I was already reading at a 5th grade level, and decided to move me up to first grade, without really giving me freedom of choice.

I was taught to read at a young age. When I arrived at kindergarten, my teachers and parents discovered that I was already reading at a 5th grade level, and decided to move me up to first grade, without really giving me freedom of choice.

So it was a completely random day in January when I was ushered into a first grade classroom and stared at by 20 judgemental little kids, who I soon became alienated from. This “upgrade” to first grade felt more punitive than rewarding, and I often wished I wasn’t there. I was made fun of, and besides that, every class until fifth grade felt painstakingly slow and ridiculously obvious. I loved learning but hated school. I despised the way the teachers taught down to the kids who didn’t care about school.

I made it through elementary school, and eventually the rest of middle school. It even became fun when I fell in love with jazz and playing the flute in the school band. There, I met and became close with several people who went on to become my best friends: Cayman and Paige, who I was already friends with from elementary school, Nico, and Niko. Though we didn’t have the maturity or richness of experience to connect with each other on a deep level, we made each other laugh, and that was what I needed.

I had a desire, beginning in 8th grade and intensifying through freshman year, to understand others. I became conscious of the fact that others were going through problems I had never been exposed to, and deeply wanted them to confide in me. I was searching for a change in my life.

My time by the river was the change I had been looking for. Seeing something so simple, like one hug, mean so much to someone made me realize that I wasn’t doing enough to connect with the people around me. Outward Bound closed the gap that elementary school opened and taught me things I failed to learn as a young kid. The trip made the experiences and people in my life seem finite and fleeting, something to be maximized.

I take that philosophy forward and think of it each day. I do my best to listen more than I talk, though I admit I am not successful very often. I have learned how to see people for who they are and love them for it. Though I fell out of contact with most of the people I met on Outward Bound, they made me who I am today. I see them in anyone I meet who fights against themself, or anyone who’s empathy goes beyond their capacity to show it. Most of all, I see them in myself and the way that I view the beautiful world around me, as it shows me new bends in the river.