Anytime she enters a room, the first thing you’ll notice about her is her shoulder-length, bright pink hair. “If I’m gonna have white hair, why not have pink hair? Or purple hair?” she explains, between sips of her iced dirty chai latte. This mentality perfectly embodies the vibrant Laurelee Roark, a 73-year-old woman who has dedicated her life to healing women’s relationships with food and body image.

Sheila, Laurelee’s tiny white poodle, brushes against her shoes, wanting attention. Her chunky silver bracelets clink together as she leans down to scratch the dog’s fluffy ears, and around her neck hangs a black cord with a heavy spiral-shaped silver pendant.

This spiral is the logo of Beyond Hunger, a non-profit organization that Laurelee co-founded in 1985. The swirl represents the organization’s mantra: healing always begins from the inside and makes its way outward, which was inspired by her own recovery journey and personal beliefs.

Growing up in San Antonio, Texas in the late 60s and 70s, Laurelee was raised to fit the ‘good Catholic girl’ stereotype that pervaded Southern culture. Her single mother of four held tightly to her traditional conservative values. However, with the Vietnam War, the Gay Rights Movement, the expansion of the Women’s Rights Movement, and a new non-conformity culture on the rise, the rest of the country was undergoing immense ideological change.

“This was the start of sort of a new way of thinking and being in the world, and I was right there on the ground floor,” she recalls excitedly, leaning forward in her chair. Laurelee always knew that she was not meant for the future expected of her, strongly opposing her family’s views. Despite her family’s military history, she joined countless protests advocating for the withdrawal of US troops from Vietnam. “I have a peace sign tattooed on my back that I got in 1969, which was just not okay,” she mentions. Laurelee’s family strongly disapproved of her behavior, to say the least: “I’m still thought of as radical,” she says, rolling her eyes.

She fought strongly for what she believed in, but at home, she still felt repressed by those around her. While her revolutionary spirit flourished, her body image began to deteriorate. So, she turned to the one thing she felt that she could truly control: her eating habits. “I could control my food, and kind of control my body–and then it got away from me.”

Laurelee began modeling in her teens, which only fueled her negative self-perception and toxic eating habits that would eventually develop into an eating disorder at just 14 years old.

Vogue had started featuring slim, long-legged models on their covers. Laurelee knew that she fit this new beauty standard, because she was “naturally tall and thin, but not thin enough…which meant I hardly ate anything.” The industry showed no mercy, and would not allow her to continue modeling if she was more than 100 lbs, which led her to take extreme measures to control her weight.

Soon after, she became pregnant with her son, Clint, and quickly married her high school sweetheart. Their relationship fell apart fairly quickly, which in hindsight, made sense. “We were very young and shouldn’t have even had a goldfish, much less a child,” she recalls.

Of course, she had to change her eating habits to sustain her growing baby. But right after giving birth, she turned to drugs and alcohol to shed the dreaded pregnancy weight. “If I drank instead of ate, I got to stay thin. If I smoked instead of ate, I got to stay thin,” she explains.

When Clint was 6 years old, she packed her bags for San Francisco where she would live with her brother, who had moved there to join the gay rights movement. “I just thought it would be fun to go somewhere that was completely different from Texas,” she remembers. She became sober again, excited for a new chapter in her life.

Eventually, Laurelee decided that it was time to begin walking the difficult path toward recovery from her eating disorder. Around this time she had also found work in a hair salon, where it was the norm to throw around comments about people’s appearance. “I noticed that a lot of my clients and a lot of my friends were still struggling with eating disorders and body hatred,” she says. One day, having had her fill of incredibly triggering and objectifying comments, she put up a sign on the mirror at her station that read “MY BODY IS NOT UP FOR DISCUSSION.”

Around 1985, she began to read books on eating disorders and body hatred to better educate herself and be able to share her knowledge with others. Soon after, Laurelee met fellow eating disorder survivor Carol Normandi. They shared the same goal of repairing the damage done by diet culture and the media, and wanted to lead other eating disorder victims through their healing journey. The pair led support groups that helped countless women, which continued to grow and evolve as time went on. “Being in 12-step programs, I knew the power of groups, so I started that first group, really, for myself,” Laurelee explains. They became a nonprofit to expand their mission of helping strengthen a community that had very little funding for mental health, “or anything, really,” she adds.

At the time, high carb and low fat diets were incredibly popular. There was one book in particular–Fit or Fat by Covert Bailey–that helped push this new fad. “I remember, I used to call it ‘Fit or F*cked’” Laurelee laughs. She felt that these strict rules about eating were absurd and unrealistic. Beyond Hunger was one of the first organizations to propose intuitive eating as an alternative to diet culture.

“Our thing was that some people really thrive on carbs and some people thrive on sugar and some people thrive on veggies and vegan diets, some people thrive on every kind of thing you can think of, so why don’t we let them decide what to do?” However, this was an incredibly difficult message to get out. “It was a very radical idea that you could be quote-on-quote ‘fat’ in this culture, and still be healthy,” Laurelee explains. Despite cultural pushback, the non-profit continued to grow as more and more people became involved in their journey.

Carol and Laurelee went on to co-write two books that would be used in classrooms and meetings for decades to come: It’s Not About Food: End Your Obsession with Food and Weight, and Over It: A Teen’s Guide to Getting Beyond Obsessions with Food and Weight. Her books are some of her highest achievements: “People still use them, we still get letters from people saying this book changed my life,” she says, smiling with pride. “I’ve been on an airplane before and the person next to me is reading my book, and it’s all dog eared, and the pages are very soft like a little velveteen rabbit, and that’s happened to me a few times.”

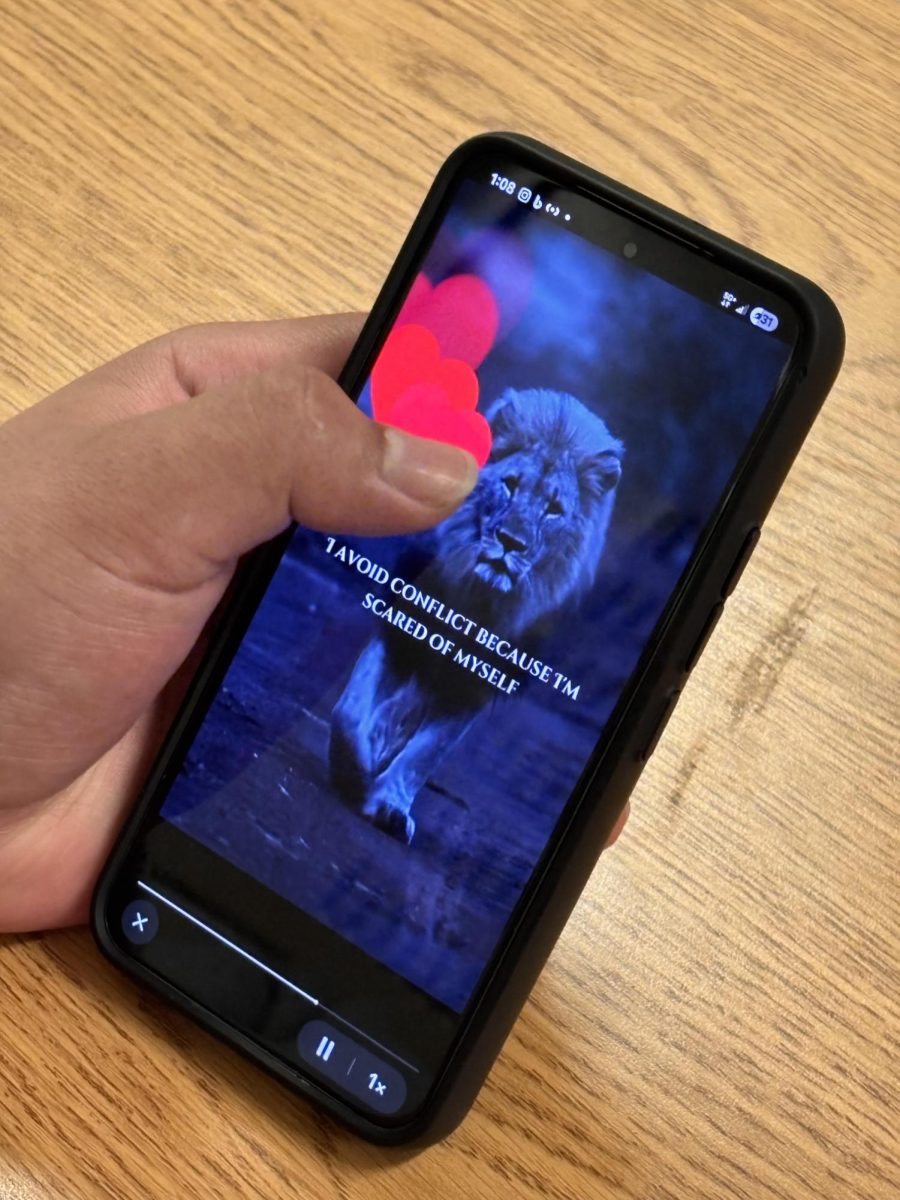

Laurelee continued to expand her work, offering personal consultations that incorporated non-conventional healing practices, and continuing to advocate for body positivity and the rejection of diet culture in her everyday life. When all face-to-face interactions were banned during a global pandemic in 2020, she began her podcast, It’s Not About Food. “Everybody was really upset about getting the COVID 20 or 40, when we’re all trying to survive a pandemic,” she remembers. “Social media was all about ‘don’t gain weight,’ when it should’ve been like, ‘don’t die.’” She knew that her expertise was desperately needed.

“I don’t even know what would be the difference between how I think and who I am, you know, it’s such an integral part of me,” she explains. Laurelee hardly sees a distinction between her work and her personal life, as she takes every opportunity to help someone work through their issues with food or body image.

Carol admires Laurelee’s dedication to each individual that she works with: “She has walked many of her friends all the way to death’s door in service of providing love and compassion to the very end,” she writes in an email.

Perhaps the most fulfilling aspect of her current work has been collaborating with high school students within the Peer Educator program at Beyond Hunger. She has helped peer educators give hundreds of presentations across Marin County to countless students, and has been visiting freshman health classes at SRHS for well over a decade. Laurelee has influenced countless lives, and continues to embody the power of creating a healthy relationship with food and one’s self-image.

Jesse Hilliard • Nov 25, 2024 at 9:33 am

Laurelee changed my life too.

I didn’t even know I had an eating disorder all of my life until I was 50. It started when I was 17. Getting skinny then getting big then skinny again. I met Laurelee and Sheila, through my therapist. We all have those moments and or events that change us forever. Moments that push us forward and change us forever. Meeting Laurelee is one of those moments for me. I don’t like to think about who I would be if I had not met her.

Thank you Laurelee.

-J

Gretchen • Nov 20, 2024 at 2:31 pm

Laurelee help me first be able to look in the mirror and love myself for the first time at age 25. She is a true gift to the world! ❤️❤️

Dorla • Nov 20, 2024 at 12:29 pm

So grateful for Laurelee Roark and her work.

She has helped many live a more healthy and fulfilling life.

Rebecca • Nov 20, 2024 at 9:25 am

A beautifully written bio on an amazing, compassionate woman!