There’s no denying that social media has distorted the way we eat and what we consider healthy. If you spend a reasonable amount of time on social media, you’ve probably stumbled upon videos of people eating massive portions of food. These videos are known as mukbangs, which translates from Korean as “eating broadcast.” Mukbangs became globally popular in 2014 but originated in South Korea as a relatable depiction of unmarried life and solitude.

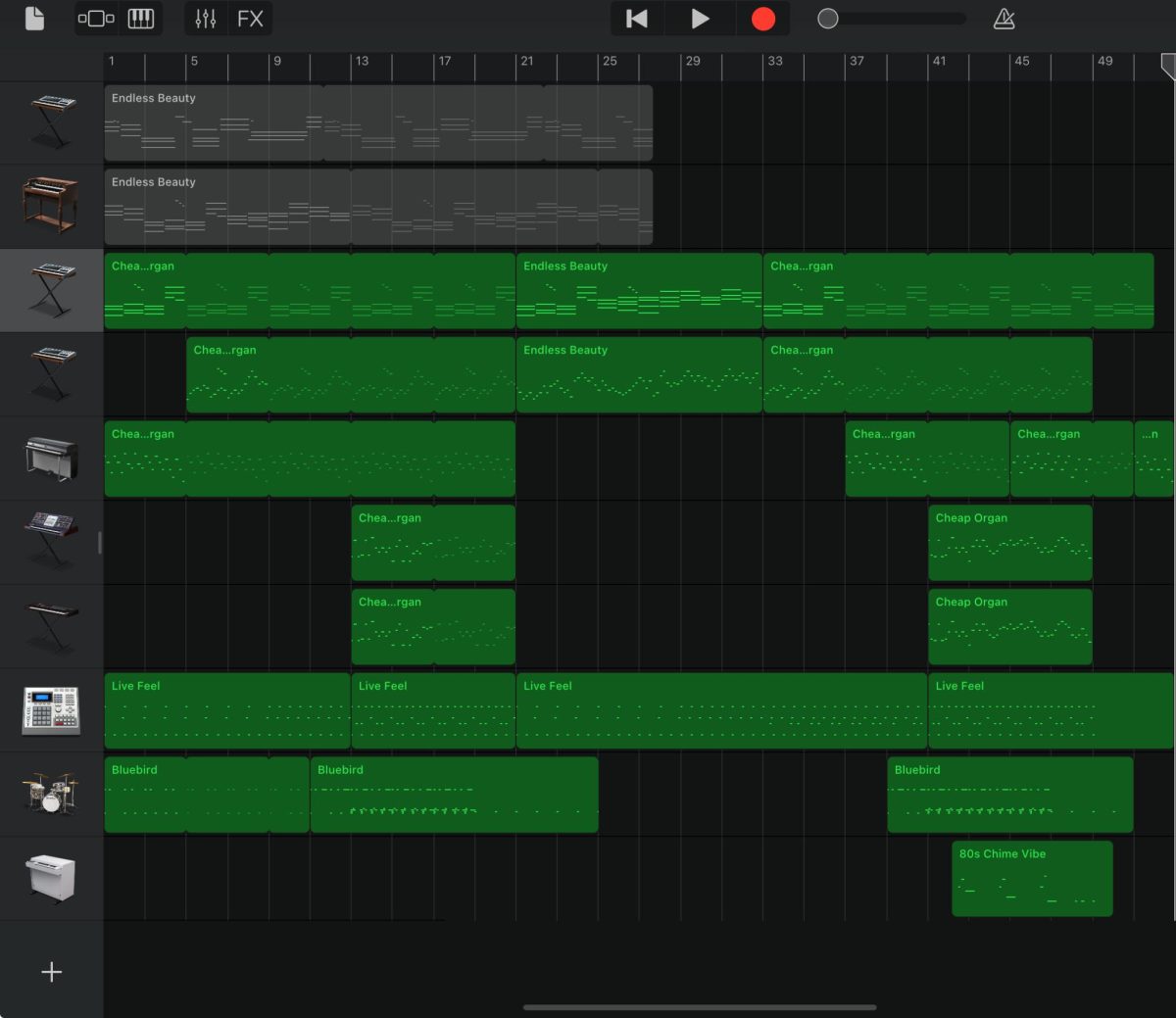

In Korea, eating meals is seen as a social activity, and dining alone can feel uncomfortable or even stigmatized. Mukbangs emerged as a way to normalize this stigma. When mukbangs made their way to Western audiences, they were embraced by many. Initially, the idea of watching someone eat for entertainment seemed odd. However, by tying it to another social media trend—“ASMR”—people became more accepting. What seemed like a harmless trend quickly developed unhealthy implications.

Imagine a three-patty cheeseburger dipped in a large bowl of American cheese and topped with a generous spread of mayonnaise. Doesn’t sound too appealing, right? Yet, to many viewers, mukbangs became a sensation because they provided the satisfaction of “eating with your eyes.” However, watching people overeat carries inherent risks.

For instance, it can trigger a relapse for individuals trying to overcome binge eating. In 2018, the Ministry of Health and Welfare in Korea announced plans to impose restrictions on mukbang content posted online. Many Korean citizens objected, arguing that eating disorders had no direct correlation with mukbangs and that restricting content infringes on freedom of expression.

Still, others believe mukbangs contribute to unhealthy behaviors. A study conducted in Gyeonggi Province, Korea, found that people who regularly watched eating shows displayed poorer eating habits, such as ordering more takeout. Participants were divided into groups based on how often they watched mukbangs or cooking shows. Those in the frequent-watching group reported the least healthy diets and admitted that mukbangs had “worsened their diets rather than improved them.”

When I was younger, a relative of mine had books about keto, paleo, and other diets. I was curious if these diets worked as dramatically as the covers claimed. Out of curiosity, I tried the “military diet,” which consisted of a slice of toast, black coffee, and a grapefruit for breakfast. Lunch involved another slice of toast, canned tuna, and more black coffee. Unsurprisingly, I didn’t last the day. I was hungry and couldn’t turn down my mom’s dinner. When I told her about my experiment, she was baffled.

“¿Qué tienes de malo? ¿Estás loca?!” she exclaimed.

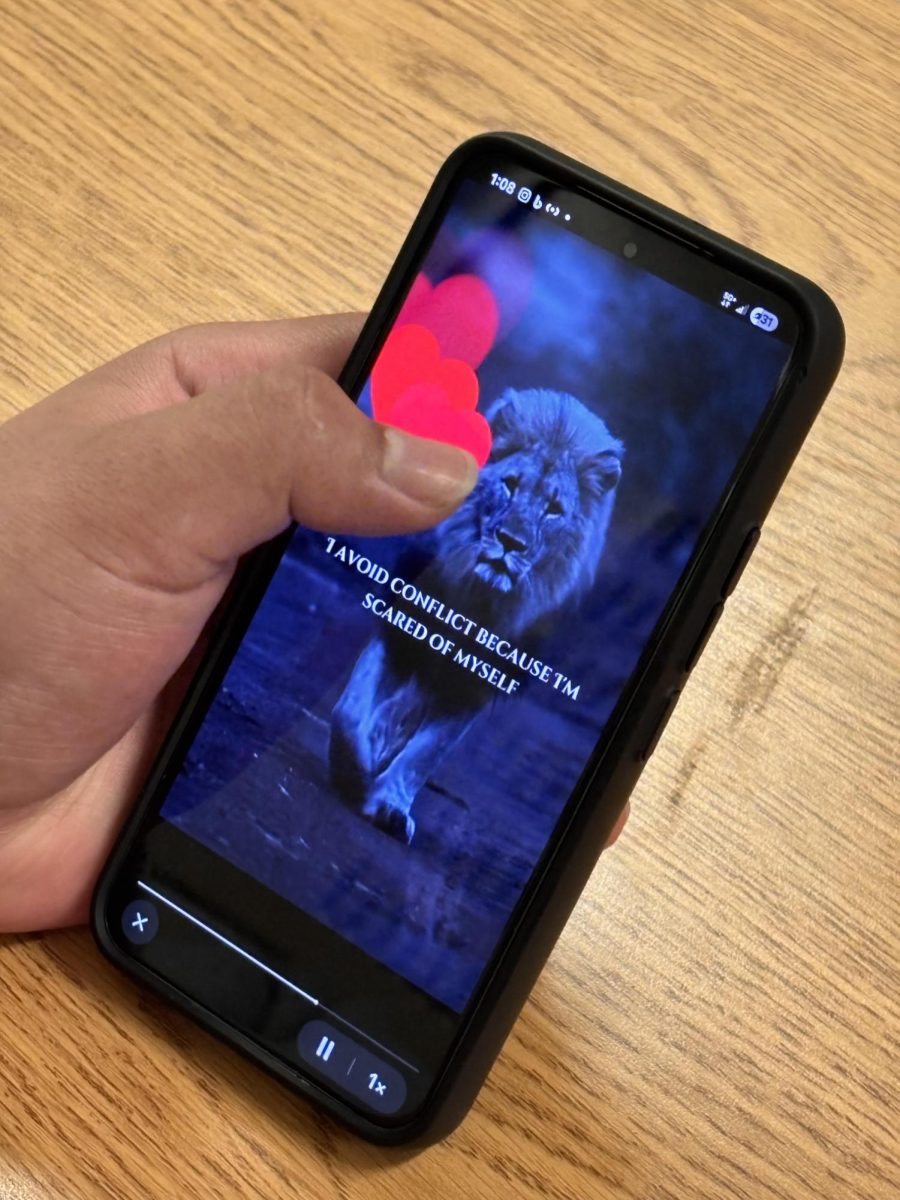

We’ve seen how impressionable children and teens are when it comes to social media trends like the cinnamon challenge, where people tried to swallow a spoonful of cinnamon powder. Social media influences our lives more than we often realize—even in something as small as convincing us to try a new Red Bull flavor. Mukbangs may not seem directly tied to eating disorders because they encourage eating large amounts of food, but showcasing another extreme isn’t necessarily better.

Many mukbang influencers are slim and maintain delicate appearances. For viewers, this is problematic. Behind the scenes, these influencers often engage in behaviors to maintain their figures, which can mislead their audience. People who diet and exercise to lose weight feel confused and disheartened seeing someone eat 10 pounds of food while staying slim.

One popular mukbanger, Fume, has 5.6 million subscribers. In a video where she eats two massive burritos, four large quesadillas, and bowls of guacamole and sour cream, a commenter asked: “Fume, you need to have another Q&A because I need to know how you can eat so much at one time. Do you eat once a day? You must exercise a lot.”

According to a 2023 article by Roisin Lanigan in The Independent, some pro-anorexia forums link mukbang videos to discourage users from overeating in real life.

Comments under videos from another mukbanger, Eat with Boki, reveal a range of reactions: “I also want to eat chocolate-covered things like that without worrying about my weight” or “I shouldn’t have watched this video when I was hungry…but now I want to eat more!” One viewer added, “Idk how they can eat this much in one freaking day.”

While some viewers use mukbangs to curb their appetites while fasting, others use them to recover from anorexia, an eating disorder characterized by an unwarranted fear of gaining weight. For example, one commenter under Boki’s video wrote: “The food looks so good, Boki! I have an eating disorder, and you’re helping me overcome it. Thanks a lot!”

Mukbangs are often described as a double-edged sword for eating disorders—they can either prompt someone to eat excessively or encourage them to fast. However, no social media post should have the power to dictate how much a person eats, especially when some creators themselves may have disordered eating habits.

Why is it important to address the problems with mukbangs? Because we can create a healthier society by being responsible about what we promote. If people were educated about food and how to build a healthy relationship with it, fewer individuals would fall into patterns of disordered eating. Globally, health reform in America is needed. Many Americans rely on fast food and convenience store meals because fresh vegetables and healthier options are often more expensive. It’s no coincidence that the cheapest food is often the least healthy.

As economic pressures grow, people prioritize rent and bills over fresh, nutritious meals. If fresh food were more affordable, we could tackle the obesity epidemic in the U.S.

Rather than letting social media teach children how to develop relationships with food, we must educate them early, before they’re exposed to harmful content that might lead to eating disorders.