My first experience seeing a food bank in person was on a Wednesday morning, over a decade ago. Before heading to the dentist’s office, my mother and I would patiently wait outside of the Marin Community Clinic. I remember hearing an abundance of people talking, seeing people setting up tables filled with food, and a line forming at the back of the clinic. Confused, I asked my mom what they were doing. In response, she said, “They are giving out food to people who don’t have the means to buy it themselves.” They headed out with a huge box filled with plenty of food that, when I was young, seemed like it would take years to finish.

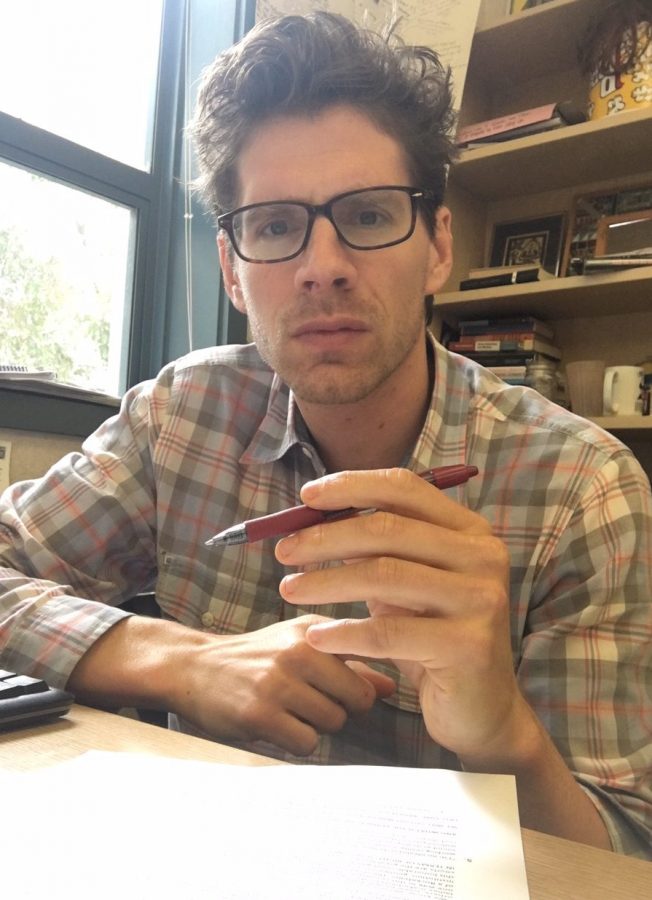

Angeline Phan, a San Rafael High School senior, explains the struggles of living in Marin coming from an asian immigrant home. Identifying with the minority of asian families in the Canal, Phan’s perspective on Marin was originally confined to her experience living in that area. However, as Phan entered her teenage years and moved out of the Canal, she saw Marin as a whole and realized it was a predominantly richer area compared to the one she grew up in.

“It was a bit difficult growing up and realizing how marginalized I was. As an Asian American and a person of low income, I felt oppressed growing up due to my socioeconomic status and other marginalized communities being oppressive towards me and my family,” says Phan.

Being low income and raised by a single mom, Phan argues that the biggest issue in Marin is the high cost of living and affording a place to reside in. “Rent is ridiculously high, paying thousands and thousands of dollars a month for a tiny apartment makes living in Marin a huge challenge,” says Phan.

Due to the high cost of living and only having one source of income, it was hard putting food on the table. Phan’s family relied on food banks and other community programs because they were struggling with many things at once.

Marin, although beautiful and diverse, is notorious for its “rich county” reputation and is an expensive place for even its own residents to live in.The cost of living in Marin is exponentially higher than living in other areas in the state. In the Marin Independent Journal, “Marin remains among most expensive US counties to rent,” their article states, “[The] National Low Income Housing Coalition’s “Out of Reach” study report, notes that tenants in the three counties must make $60.96 an hour to afford to rent a modest, two-bedroom home estimated to cost $3,170 a month.” It further explains, “Annual income of $126,800 is needed. That’s about $61 an hour, significantly more than the state and local minimum wage.”

Just living here in Marin is expensive alone, and on top of providing a home for your family and food on the table, being able to afford other things such as wifi or a way of transportation is a very difficult task for even a regular medium household income to provide.

Something else to note is the prices for food have increased in just these past few months. In the article “Bay Area prices up 2.7% as inflation trend cools” written by the Marin Independent Journal, they state that, “The Bay Area inflation rate, as measured by consumer prices, rose by an annual pace of 2.7% in February compared with the same month the year before.” Not only is the cost of living in Marin high, but the food we buy for necessity increases in price which makes it further difficult for people to be able to live.

The economic struggles are not only shown through numbers but are also reflected through people’s lives. The rise of food prices and cost of living in Marin has made more and more people rely on the food banks for help.

Dee Lacerda, the pantry coordinator for the food bank at Anthem Church, watches as a Hispanic woman pushes a stroller that her baby is sitting in. She approaches and asks Lacerda if she is able to get food. Lacerda tells her that she’ll need to apply to the food bank to get groceries. The lady softly repeats, “Can I get food today?” Lacerda is familiar with language barriers, and new visitors who are unfamiliar with the food bank in general. She lets her move past and get her food for the week, not wanting to stress her out with the lengthy application process. The lady pushes her stroller and happily goes and waits in line grabbing a white bag to collect food.

Lacerda has worked at the food bank for over ten years. As the pantry food coordinator, she is involved in scheduling the days volunteers show up at the food bank. She keeps a record of newcomers coming in to collect food in order to make sure all people registered are able to obtain food. From working at the foodbank for many years, she’s seen that the need has gone up every year. “It costs so much money to live here, the system is only built for the affluent,” Lacerda says with a sigh.

The cost of living is not only expensive in Marin but also in other parts of the country. There’s a huge income disparity between the affluent and the poor that makes it more difficult for those below the middle class to be able to just live. The San Francisco-Marin Food Bank is a non profit organization that donates food to many local food banks in Marin. They send over 60 million pounds of food yearly. With how big this organization is, it shows there’s a huge demand and lack of access to get food.

What you can’t buy at the store, the food bank can provide with sufficient resources available. “Most grocery stores throw away food that they don’t sell, and programs like the SF Marin Food Bank and the Marin Community Fridges, help give the food from these stores so it’s not thrown away,” says Lacerda.

“Because Marin is an exclusive community, there is a low amount of supply and a greater demand that increases the price to live in Marin,” says one of SRHS’s economics teachers, Abigail Spaelti.

In our country there is a huge disparity between wage gaps, but it’s predominantly shown more in Marin due to how expensive it is. According to the website CalMatters, California has the minimum wage being at almost 20 dollars. Even at 20 dollars, the minimum wage is not enough to be able to live, you’re just surviving.

Zully Lopez has been working at Canal Alliance and has recently been more involved as a coordinator for their food bank . Like Lacerda, Lopez provides SF Marin Food Bank with the number of people coming in and getting food at the food bank. She stays up to date with the training in food management and safety and overall running the food bank program.

Lopez notes that because of the different incomes there are in Marin, the food banks here help with the disparity seen throughout Marin. “There’s been pop-up pantries in Canal, by Pickleweed Park, and another in Marin Community Clinic,” says Lopez.

During the time of Covid-19, these pop-up food banks have appeared because many people had lost their jobs and had very low income that just the food pantry at Canal Alliance wasn’t enough. In the article “Look How Far We’ve Come: COVID Recognition Event at the Food Bank” by the SF-Marin Food Bank, they state, “I’m so proud for many reasons. Including the fact that we operated 28 Pop-up Pantries at the height of the pandemic, relying on the ingenuity and collaboration of our staff to meet the massive need,” said Executive Director Tanis Crosby. The pandemic further showed the disparity between the affluent who could afford food and those who couldn’t. It was a great challenge to be able to work and provide for your family unless you had a stay at home job, or reserves of money saved up. The pop-ups that were only going to be around for a few weeks, have stayed for over five years and continue to help out the community.

Gloria Barrios, known locally as an advocate for the Hispanic community and event planner, explains the many difficulties faced throughout Covid-19 at Canal Alliance. During Covid-19 on Tuesdays before 7am, big food trucks would unload crates filled with food. Volunteers would set up a long row of tables where they placed the boxes of food and organized it from vegetables and fruits to the meats and grains. The volunteers with masks, plastic sheets and gloves on their bodies made for an unsettling feeling of the end of the world as they packed the food in bags for people to take. A huge line would form from Canal Alliance to the supermarket Mi Tierra, that covered 0.2 miles but felt unending as the hours went by.

Looking at the ground, Dee sighs as she also explains the events that happened at the food bank during Covid-19. “Each volunteer had to prepare 10-12 bags of food, in the end having prepared over 80 bags of food before 7:30am on a Saturday morning,” says Lacerda.

Adults and children worked together throughout the stress that Covid-19 placed upon everyone. Even though people were masked up, emotions and intentions were never hidden as volunteers continued to support food banks even when the world seemed practically over.

During the height of the pandemic, SRHS senior Vannessa Lopez explains that there were many challenges her family faced. She recounts the socioeconomic barriers she faced in response to the lack of household income after her parents lost work. Vannessa comes from an immigrant home life where her parents earn a stable income, and have the means necessary to be able to live.

“There would be times where my parents would and wouldn’t have work off and on,” says Vannessa. The food bank would help them out by saving money when they barely had any in order to provide the necessary means of living.

Not only did the Covid-19 affect Vannessa’s quality of life but it did to many others. Christian Canovas, an employee at SF Marin Food bank, says, “The need for food increased during the pandemic, ⅙ people needed food before the pandemic, five years after the pandemic that number changed to ⅕.“

Canovas is in charge of volunteers and has been working at SF Marin food bank for about eight years. He explains that most people might think only the homeless population goes to the food banks but in actuality, they only make up 3% of the people receiving food from food banks. This reveals that about 97% of the people receiving food are those who have homes but can’t afford basic living necessities in order to survive by themselves.

“[The food banks] help everyone to get their necessary food staples in order to be able to cook a homemade meal,” says Lopez.

Sophomore Arianna Cooper from SRHS was raised by her grandmother who immigrated here when she was a teenager from El Salvador. Certain circumstances occurred, which led to Cooper’s family having some difficulty in having the financial resources to provide food for their family.

“My grandma heard that there was going to be a food bank, so she took us to go because it was going to be free,” says Cooper.

Cooper’s grandmother now works for Medi-Cal and is a part of the school board, and is in a better financial situation. In that time when Cooper’s grandmother didn’t have these jobs, there was a struggle, financially speaking. Because Marin is such an expensive place to live in, making certain financial decisions could be a difficult task.

Other programs such as Community Action Marin also try to help out with the disparity in Marin. Community Action Marin has their own local garden where they get the produce to make 600 meals a day. The garden produce goes to their very own kitchen where they make meals from scratch to provide nutritious foods to those in need of it.

Debbie Harris, director of food and climate justice, who has worked at CAM for about a year now says, “I feel excited in being able to solve systemic problems that seem unsolvable.”

Phan, Lopez, and Cooper’s experiences paint the picture for how there is an economic disparity in Marin and how Food Banks try to fill in that gap. Reflecting through my own life, watching my own mother going to the food bank and needing help, it made me want to start helping out my own community in any way I could.

It’s been almost about 10 months since I’ve started to volunteer at the Marin Community Clinic’s food bank to gain some volunteer hours for my high school’s California Scholarship Federation. Every Saturday morning, my friend and I wake up at 6:30am and get ready to start volunteering promptly at 7:30am. Upon arrival, we are greeted by the sight of a huge food truck rolling in the parking lot to deliver the food we are about to hand out. Crates full of huge boxes of food are laid on the floor as we are setting up the tables preparing to stack the food on top of them. The colorful variety of ingredients ranging from fruits and vegetables to the meats all coordinated in order as if lining up for war. I put my gloves on, a box full of food in hand, and I was ready for battle.

As we volunteers wait, like soldiers armed in this war ready to fight, getting to pick the food I hand out is a very crucial task for me. The crunchy, round, green grapes, is the thing I spot out for as I race against my friend to get to choose my pick of food. The crunchy textured bag scented with a sweet aroma filled with grapes is the most loved item at the food bank, which makes me want to be the one to hand it out. Volunteering has evolved beyond an extracurricular opportunity into a shared emotional experience between the food bank’s patrons and me. Every step, from getting to pick the food to hand out, to providing exhausted parents with food, and watching children jump up and down while being handed food, has all collectively put a smile on my face anytime I volunteer. Even through the morning cold, shivering uncontrollably, handing out food feels like a never ending warm blanket, wrapping around you like a hug.

We prepared for war very well, a line of people form a line around the corner of the clinic, and most of the volunteers had most of their food items already on top of the table. The people are greeted by a volunteer who receives their card information in order to take note who arrives at the food bank and who doesn’t. Everyone who first arrives at the food bank has to fill out a form and put in a bit of information of who they are in order to be put into the system as a frequent returner to the food bank. That way when they go to the food bank, it’s an easier process to check in which allows for the food bank to estimate how much more food needs to be provided.

“Because some people weren’t able to obtain formal education from their country, or don’t have the access or opportunity to do so now, or have access to high paying jobs, the system keeps them in this cycle of poverty which is why the food pantry is so important to keep,” says Lopez.

Hunched over, carrying a small bag to hold food, an elderly Vietnamese lady looks up at me and points to the grapes she wants. I happily give her the bag of grapes, she smiles, raises her pointer finger asking for one more; she walks away with a warm smile and with two bags of grapes.

Even without being able to speak the same language, there’s this sort of mutual understanding between the volunteers and the people; a language of understanding and communicating through food. Talking only does so much but actions like giving food is a sort of language most people will understand.