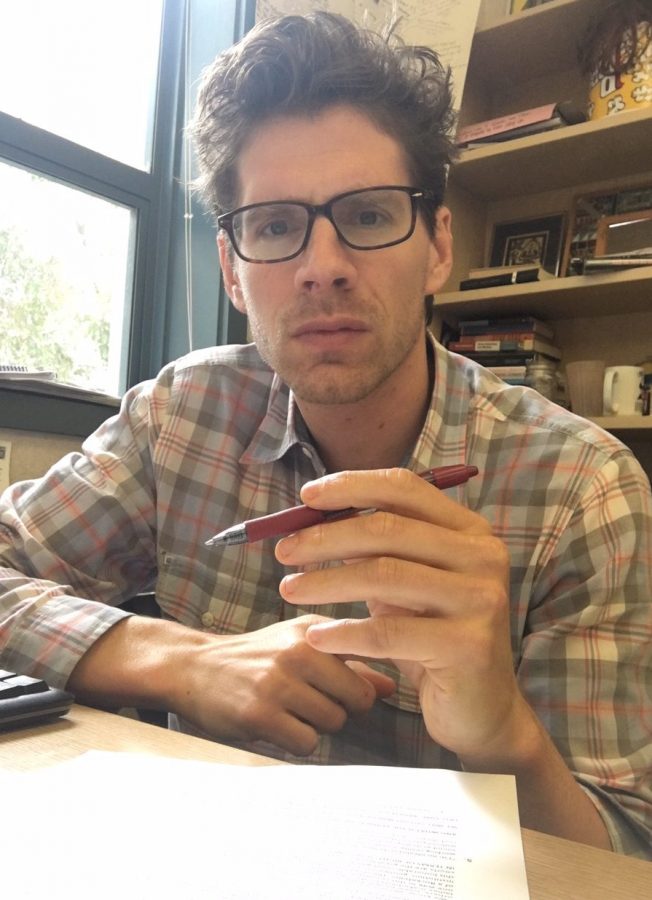

Senior athlete Gio Hernandez played soccer for all four seasons during his time at San Rafael High School. At the start of his freshman year, he played for the Junior Varsity team, but halfway through his first season, he was called up to play for the Varsity team for the next 3 years. Gio had been playing soccer since he was 7 years old, and he had always known he wanted to play in college.

Like many other high schoolers who know they want to pursue sports in their adult life, they begin to practice and play their sport at a very early age. For soccer, Gio says that if an athlete wants a chance to play soccer professionally, recruitment and making oneself stand out to coaches are essential.

Gio went through the same recruiting process that many soccer athletes go through in order to receive a spot on a college team. He explains, “Recruitment is a pretty long process. I initially got an offer from a school named Bushnell up in Oregon. As for Santa Cruz, the process started in December, when I started emailing them. After emailing them consistently, sending videos and clips of me playing, they told me to go to this ID camp, where I played really well. With my film, and me playing well, I think that gave [UCSC] the green light, and I accepted the offer immediately.”

In Gio’s words, ID (Identification) camp is a big part of playing soccer, or any college sport in general. Gio explains, “[ID camp] is a recruiting event, where you go to a camp that the school hosts, where they come out to watch you play whatever sport you’re playing.” In other words, coaches observe and evaluate high school athletes at these camps that are designed to showcase players’ skills and provide them with feedback. Not including all the time and effort you put into a sport, you also need loads of money for clubs and any other place where you play soccer.

Because Gio has played this sport for so many years of his life, he has contemplated quitting the sport several times. He would have negative thoughts like he wasn’t good enough and work himself out trying to be better in order to play, and receive athletic scholarships in college, and also deal with an injury that happened in his junior year. This is what he thinks caused him to eventually burn out. When asked why he couldn’t go through with quitting, he says, “I wanted to give up, but it wasn’t easy because my love for the sport didn’t allow me to.”

In Gio’s junior year, he broke his foot, and that injury ended his season that year. He was on crutches for that whole year and struggled to become dependent on others. He says, “I had taken something so small like the ability to walk for granted, and now that I couldn’t, I couldn’t do anything without help, like how I’m not used to doing.” Alongside the physical pain, he endured the hardest part was the emotional aspect that hurt him the most. This injury was going to be the biggest competition that Gio would face. He describes it as a “Gio vs Gio” battle that was affecting his mental health. At practices, he would sometimes show up just watching from afar, witnessing his teammates improve as his talent was slowly fading away.

Not only did this injury affect his athletic performance, but his life with friends and family. He made his best attempt to hide all of the stress during school and play it off as best as he could, but when he would arrive home every day, it wasn’t easy. He explains, “I see why athletes get severely depressed when you dedicate your whole life to the sport and go through burnout. I can’t imagine myself without soccer, and it scares me to think who I would be without soccer.”

Gio knows that future injuries are bound to happen anytime, any day. He knows that he will never see it coming and that there will be no way to prevent it, but he is willing to take that risk and stay disciplined and persistent. He knows that eventually, he will be back again.

Gio will be playing soccer at UCSC for the NCAA Division III. He received a scholarship of $18,000 to go play for them. He will be majoring in electrical engineering, and he shares his ideas on how he plans to balance academics and soccer. He says, “I see myself pulling all-nighters and from what I’ve heard from current [UCSC] athletes, they do early training, so I’m assuming I’ll be up early and then definitely going inside any office hours and making use of my weekends.”

According to the AASP Blog, a blog associated with the American Society of Safety Professionals (a professional organization dedicated to occupational safety and health), researchers examine the psychological factors of burnout in high school student-athletes. Their studies acknowledged the physical, psychological, and social demands that student-athletes continuously navigate through in high school. Researcher Moen and other colleagues did a study in 2017, where they focused on the psychological determinant that was contributing to this “burnout”. They found that significant predictors of burnout included negative effects like sadness, anger, guilt, and worry. In other words, student-athletes who experienced negative affect or worry had a greater chance of experiencing burnout.

Another determinant of burnout is the physical factor. Negative emotions that can range in severity from sadness and depression show exhaustion not just emotionally, but physically, to the human body. This exhaustion can result from excessive training and competition without adequate rest and recovery. It becomes more likely that athletes experiencing injury and illness will negatively perceive their performance, which can contribute to burnout.

Researchers Raedeke & Smith used the Athletic Burnout Questionnaire in 2001, and the Recovery-Stress Balance Questionnaire 36 Sport was used by researchers Kallus & Kellmann in 2016 to assess athletic burnout in athletes. The Athlete Burnout Questionnaire (ABQ) is a widely used instrument for assessing athlete burnout. Whereas, Questionnaire 36 Sport is a tool used to assess athletes’ perceptions of stress and recovery in the context of training and competition. It helps monitor the recovery-stress balance, identify potential under-recovery states, and inform training and recovery practices.

Each student-athlete has a different experience with burnout, as it can show itself in different ways. Therefore, when addressing or preventing burnout, it is crucial to use an individualized approach for each student-athlete. Here at SRHS, seniors are debating whether or not to choose to pursue sports in college, despite their experiences with burnout.

CJ Harter, another student-athlete at SR, played football for three seasons. Freshman year, he played on the Junior Varsity team, played for the Varsity team his sophomore year, skipped junior year, and returned to play on the Varsity team his senior year. Freshman year, he realized he was interested in playing football in college. But as his senior year was coming to an end, he realized just how much of a time commitment football was going to be. To him, it was important to choose a school with great academics, but trying to pursue football and balance academics at the same time would’ve been difficult, in his opinion.

During CJ’s junior year, when he was not playing football, he attempted to try out for baseball instead so he could be recruited by a college team. He believed that if he worked hard and had a good junior year season, he would have a chance to be scouted. Some issues that he faced were difficult experiences with teammates and overall not playing well. When senior year started, he made the decision to go back to playing football and to make sure that this year would be memorable for him.

Not pursuing baseball was not the ideal plan CJ had in store for himself. He realized that he did not love baseball as much as he used to when he was younger. The sport no longer gave him the same sense of joy it had used to. But despite these setbacks in choosing a sport, he has no regrets because both sports gave him lessons and made him gain experiences that have shaped him to be the person he is today. Looking back on CJ’s junior year, he acknowledges that he experienced burnout. At the time, he called it stress, as he was juggling AP classes and AP tests, and at the same time practicing baseball for months, despite him no longer having fun.

CJ describes his experience with burnout by saying, “Burnout is a very real thing that a lot of athletes go through. Burnout can be especially hard because it can feel like a silent battle that you have to deal with yourself.”

Now, CJ has chosen to pursue his academics as his main focus instead of sports. He had long conversations with his dad about whether or not he should play football in college, and it wasn’t an easy decision to leave football behind. His father and coaches were always super supportive and would be willing to help him, if asked, with the resources needed for him to pursue athletics in college. When CJ was asked if he second-guessed his choice, he responded by saying, “Yeah, I sometimes feel like I should have pursued playing football in college. I feel a little bit guilty because I feel like I could play football in college, but I just feel like my college experience is more important than sports right now.”

CJ hopes to help the football team, along with the other football coaches, during the summer. He will be attending a college at Colorado School of Mines, majoring in mechanical engineering, with academic scholarships. A piece of advice he would give to future seniors who find themselves in the same shoes as him is: “Do what your heart tells you and don’t feel pressured in any way to make a decision. In the end, everything will work out the way it’s supposed to work out.”

Being signed and scouted for junior year is a unique experience that Sophia Everett, a softball player here at SR, went through. She was signed by UC-Berkeley in her junior year. For all 4 years of high school, she has been on the Varsity softball team.

Sophia started playing softball when she was eight. She started with recreation leagues, and once she turned 10, she began to do travel leagues. She used to play T-ball with the boys in her elementary school and also play basketball during lunch. And sometimes baseball outside of school. Not only did Sophia play for her softball team, but she also played on the basketball and volleyball teams at SR.

When Sophia was asked what it was like to play 3 sports in high school, she said, “It’s kind of cool. I feel like a lot of sports translate into other sports. Like throwing a ball in softball is similar to hitting a ball in volleyball and basketball.” Sophia opened up about her concerns about playing a competitive sport in college. She shares, “I’m actually very nervous because I will be majoring in [psychology]. I originally wanted to major in business administration, but I know going to Berkeley will be crazy, even if I weren’t going to play a sport. And if I try to go to business and play a sport, that’s going to be hard and mentally challenging.”

Sophia didn’t know she would be playing for UCB’s softball team. She made visits to other campuses, and that’s when she visited Berkeley, where she describes that UCB felt like home. Sophia’s family and friends were all very supportive. She had family visit her, friends congratulate her, and her coaches were overall very proud of her.

Sophia always knew she wanted to play in college, but freshman year, she faced her obstacle of burnout. After years of playing since she was eight years old, high school baseball wasn’t the same as playing in leagues. High school baseball also requires you to do well academically, just like any other sport, if you want to stay on a team. Freshman year, she faced a big burnout phase in freshman year. The reason being that she felt like she was being pressured to play, that it was no longer by choice. It felt like she didn’t love the sport anymore.

Although she wanted to give up, she decided to take a 3-month break in her freshman year and came back, more determined and motivated. Sophia will be playing softball at UCB for NCAA Division I, with a full scholarship. Playing in college has been her dream since she was a little kid. A piece of advice Sophia gives to any seniors struggling with choosing to do sports in college is: “Think about the good memories you have from the sport and ask yourself if those memories can outweigh all the cons.”

Coaches can be a valuable resource for communication, allowing athletes to reach out for help when struggling with burnout or academic difficulties. Here at SR, previous athletic director Jose De La Rosa and soccer/tennis coach Nichole Caiocca are both well known for the support they offer to any of their athletes.

Jose De La Rosa (also known as JDR) is a PE teacher, JVB, and Varsity soccer coach at SR. De La Rosa played soccer growing up. He didn’t play in college because of the financial component of playing on a college team. He played FC (Football Club) since he was seven up until a little after high school. When he graduated from college, De La Rosa’s younger brother was going to be a senior at SR. He did not like the state of the soccer program at the time, and so he was committed to coming back to SR to coach in 2017. This then led him to become the athletic director for six years before becoming a full-time teacher.

De La Rosa believes it is difficult to pursue any sport. He says, “Out of all the students that play high school sports or played youth sports growing up, I think only seven percent play in college at any level.”

De La Rosa also believes college sports are more than just the higher divisions. Just like playing at the higher division levels, he mentions that playing sports at junior colleges can be a lot easier, but there is still a lot of work that goes behind it, like your eligibility. A student has to be NCAA eligible, but also academically eligible by keeping up with their grades.

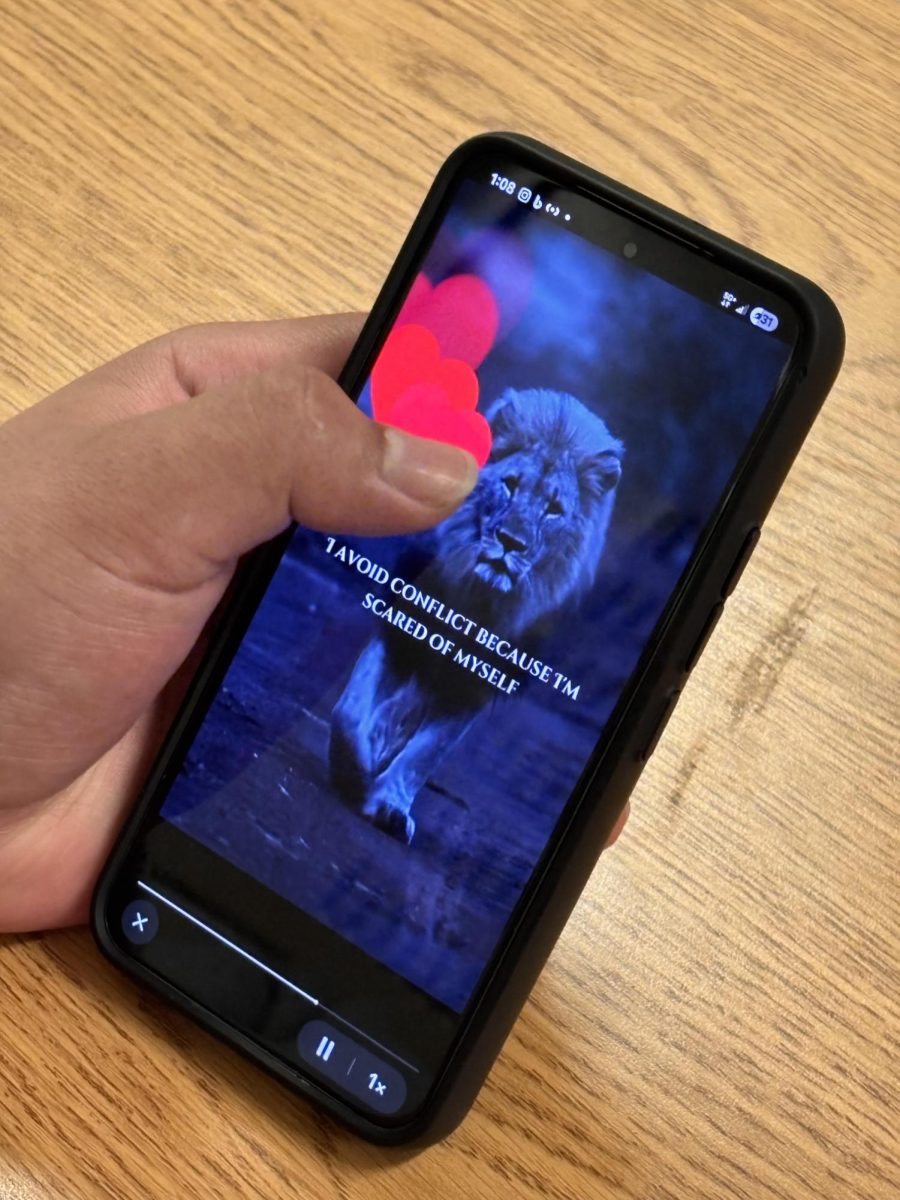

He says, “People don’t look at D2s or D3s, they think it’s only Division one. Young athletes only see what’s on TV and what’s on Instagram. So I think that dissuades students from continuing to the professional level. [Sports] becomes more of a job, and I think what a lot of people don’t see is there’s a lot of work behind getting recruited, or even playing in college, whether that be at any level.”

Similar to JDR’s beliefs, Caiocca thinks that being more open to lower divisions gives you more of an opportunity of being able to play, especially after putting years of commitment into a sport. She says, “I think a lot of student athletes have spent a ton of time on their sport, tons of years looking to be successful. I think you really need to envision what your life is gonna be like at that certain college, or if your life is gonna be without that sport, is that something that you’re okay with?”

Caiocca is a current math teacher and also coaches girls’ Varsity soccer and girls’ golf. She also helps out with the boys’ golf team as well as lacrosse. But her main focus is girls’ soccer, which she has been coaching for 10 years now. Caiocca previously coached at another school before she started teaching at SR. She grew up training and helping coach, and her personal coaches were a huge inspiration in her life.

Caiocca has played all the sports that she’s coached. She grew up playing soccer since she was a little kid, played varsity soccer in high school, but decided not to play in college right away. She ended up going back with some eligibility remaining, and so she played at the junior college level at JC City College of San Francisco. After junior college, Caiocca was accepted to CSB, which for her was a good academic match, but she didn’t have the opportunity to play there.

A piece of advice Caiocca shares is: If you want to play in college and you’ve taken care of the academic piece, there is a fit for you somewhere. A lot of times, people think about the big-name schools, but there are so many other offerings. Students could utilize junior college to transfer or some NAIA schools that aren’t just on TV, if that’s an option for you, that’s awesome, but there are so many other options, too.”

Another teacher and coach who has a lot of insight on students wanting to do sports in college is Catherine Healy. Healy is a current PE teacher and a freshman girls volleyball and JV boys volleyball coach. She was also a previous girls’ Varsity basketball coach here at SR.

Healy’s first year at SR was back in 2002, where she was studying to become a PE teacher, but also started coaching basketball that same year. SR needed a basketball coach, and so she became the girls’ Varsity basketball coach after she was talked into it by other coaches. Healy also played basketball in college and considered playing to become a professional player. She tried out for the national team but decided to stop at around the age of 25. She considers basketball to be the main sport that she can coach at the highest level.

She also started coaching volleyball when her daughter was attending SR. She coached her daughter and her friends up until they all graduated two years ago. She has also coached junior varsity teams, and she says that coaching lower levels of any sport provides an opportunity for kids to play in high school. In Healy’s 23 years here at SR, she says she can remember 10 of her athletes going pro or doing sports in college, not including the junior college athletes.

Healy’s daughter, Mary Healy, graduated with the class of 2023 and is currently attending Washington State University, playing volleyball at the NCAA Division I. Healy describes that now that both of her kids are in college, she gets to enjoy the fruits of their labor as she watches and supports. But it wasn’t easy to see her children where they are now. She says that the recruiting process is heartless, and the amount of money you need to invest in recruitment is not easy either.

When Mary Healy was in high school, Healy paid for everything. She says, “I probably spent around $80,000 over the six-to-seven years overall. But now, Mary is receiving a full-paid scholarship, so that’s a relief. I don’t have to pay for anything anymore.” As for Healys’ son, Jack, he didn’t play many travel sports, making it slightly less expensive.

Healy has seen her athletes choose lower divisions to improve and better balance sports and academics. She says, “I think that people downplay or don’t appreciate the fact that you have a greater chance of finding happiness and success in lower divisions rather than constantly trying to get recruited to D1. D1 is really, really hard. It is a business. And finding a spot on a roster in D2 or D3 or in a NAIA, which is like below the D2 or in junior college, means you get to play on a team in a school. You get to be a part of something. I think more people should consider the lower levels.”

A piece of advice Healy would give to any student athlete who is having trouble managing their sports and also managing their time with academics is: “Athletes spend two to four hours a day on their sport. We get two hours a week in advisory, use that time. Do not socialize. Go somewhere where you’re gonna work and be productive. If you have a period off, you gotta use that time. If your teachers don’t know that you’re a committed athlete who’s doing all these things after school hours, they can’t understand you or what you’re going through in order to help you.”

As for my own experience, I personally never made it my own goal to become overly great or successful in any sport. I played soccer for a small team from the ages of 6-10, only because my dad made me. But after some time, I grew to enjoy it. I wasn’t necessarily the best, but I also wasn’t the worst. I was good enough to have playing time and be on the starting team, but I wasn’t good enough to join a club and gain a career from it.

And I was okay with that.

Freshman year of high school, I knew I wanted to play a sport, but I wasn’t sure which. So I resorted to the sport I was most familiar with. I went to the soccer meeting to get information about tryouts, but the next day, as I listened to the school’s announcements, I heard that the cheer team was also having tryouts. I attended tryouts and made it on the JV team.

My first year was tough. I didn’t know my teammates, and I wasn’t used to getting home around 7 pm. I had a hard time doing homework as a first-year high school student, and it created bad habits. So as the first season ended, the second season started immediately after, and I wasn’t sure whether or not I wanted to keep cheering. Fast forward to 3 years later, senior year, I had continued cheering for all 4 years.

When it came to applying to colleges and deciding where I wanted to go, I considered doing cheer in college. I would eliminate the schools from my college list that did not offer cheer as a sport, but I was faced with the reality that I was avoiding: burnout. I started contemplating whether or not it was a good choice to play sports in college. I realized that there was no way of neglecting the fact that I was no longer capable of pursuing the sport I had loved before, because cheer had become something I had lost passion for.

Realizing that burnout affected the passion I had for cheer wasn’t an easy one. But right now I am okay with pursuing academics in college instead, and putting all my effort on time on doing well academically. Cheer had become a big part of my identity, but because of that, it seemed like I let go of all the other things going on in my life.

There is nothing wrong with letting go of something you pursued for years. It is good to look back at the good moments and accept that you need to find that passion somewhere else. Whether it is to play the sport as a hobby or discover a different athletic passion, like going to the gym or going on long runs. After all, participation in athletics or any active hobby has numerous benefits, such as mood-enhancing effects and development of life skills. and a sense of belonging to a community.

Cheer taught me many lessons and shaped me into the person I am today. To anyone struggling with burnout, I would advise them, “If you are willing to take many risks and make sacrifices, don’t give up on your goals, even if it’s hard.”

Spanish Translation:

Gio Hernández, atleta de último año, jugó fútbol durante las cuatro temporadas de su etapa en la Preparatoria San Rafael. Al comienzo de su primer año, jugó para el equipo Junior Varsity, pero a mediados de su primera temporada, fue convocado para jugar con el equipo Varsity durante los siguientes tres años. Gio jugaba al fútbol desde los 7 años y siempre supo que quería jugar en la universidad.

Como muchos otros estudiantes de preparatoria que saben que quieren dedicarse al deporte en su vida adulta, comienzan a practicarlo desde muy pequeños. En el caso del fútbol, Gio afirma que si un atleta quiere tener la oportunidad de jugar profesionalmente, el reclutamiento y destacar ante los entrenadores son esenciales.

Gio pasó por el mismo proceso de reclutamiento que muchos atletas de fútbol para conseguir un puesto en un equipo universitario. Explica: “El reclutamiento es un proceso bastante largo. Inicialmente recibí una oferta de una universidad llamada Bushnell en Oregón. En cuanto a Santa Cruz, el proceso comenzó en diciembre, cuando empecé a enviarles correos electrónicos. Después de enviarles constantemente videos y clips de mis partidos, me recomendaron ir a un campamento de identificación, donde jugué muy bien. Con mi película y mi buen juego, creo que eso le dio luz verde a UCSC y acepté la oferta de inmediato,”

En palabras de Gio, el campamento de identificación es una parte importante del fútbol, o de cualquier deporte universitario en general. Gio explica: “[El campamento de identificación] es un evento de reclutamiento, donde asistes a un campamento organizado por la universidad, donde vienen a verte jugar cualquier deporte que practiques.” En otras palabras, los entrenadores observan y evalúan a los atletas de preparatoria en estos campamentos, diseñados para mostrar las habilidades de los jugadores y brindarles retroalimentación. Sin incluir todo el tiempo y esfuerzo que dedicas a un deporte, también necesitas un montón de dinero para los clubes y cualquier otro lugar donde juegues al fútbol.

Debido a que Gio ha practicado este deporte durante tantos años, ha contemplado dejarlo varias veces. Tenía pensamientos negativos, como que no era lo suficientemente bueno, y se esforzaba por mejorar para poder jugar, obtener becas deportivas en la universidad y, además, lidiar con una lesión que sufrió en su penúltimo año. Esto es lo que, según él, lo llevó a su agotamiento. Cuando se le preguntó por qué no pudo dejarlo, respondió: “Quería rendirme, pero no fue fácil porque mi amor por el deporte no me lo permitió.”

En su penúltimo año, Gio se fracturó el pie y esa lesión puso fin a su temporada. Estuvo con muletas todo ese año y le costó mucho depender de los demás. Comenta: “Había dado por sentado algo tan pequeño como caminar, y ahora que no podía, no podía hacer nada sin ayuda, algo a lo que no estoy acostumbrado.” Además del dolor físico, lo más difícil fue el aspecto emocional, lo que más le dolió. Esta lesión iba a ser la mayor competencia que Gio enfrentaría. La describe como una batalla de “Gio contra Gio” que estaba afectando su salud mental. En los entrenamientos, a veces se presentaba simplemente observando desde lejos, viendo cómo sus compañeros mejoraban mientras su talento se desvanecía poco a poco.

Esta lesión no solo afectó su rendimiento deportivo, sino también su vida con amigos y familiares. Hizo todo lo posible por ocultar el estrés escolar y disimularlo lo mejor posible, pero al llegar a casa todos los días, no era fácil. Explica: “Entiendo por qué los atletas se deprimen gravemente cuando dedican toda su vida al deporte y sufren agotamiento. No me imagino sin el fútbol, y me asusta pensar quién sería sin él.”

Gio sabe que las lesiones pueden ocurrir en cualquier momento, cualquier día. Sabe que nunca las verá venir y que no habrá forma de prevenirlas, pero está dispuesto a correr ese riesgo y a mantenerse disciplinado y perseverante. Sabe que, con el tiempo, volverá.

Gio jugará fútbol en la UCSC para la División III de la NCAA. Recibió una beca de $18,000 para jugar con ellos. Se especializará en ingeniería eléctrica y comparte sus ideas sobre cómo planea equilibrar sus estudios y el fútbol. Él dice: “Me veo trabajando toda la noche y por lo que he escuchado de los atletas actuales [de la UCSC], entrenan temprano, así que supongo que me levantaré temprano y luego definitivamente iré a cualquier horario de oficina y aprovecharé mis fines de semana.”

Según el blog de la AASP, un blog asociado con la Sociedad Americana de Profesionales de la Seguridad (una organización profesional dedicada a la seguridad y salud ocupacional), investigadores examinan los factores psicológicos del agotamiento en estudiantes-atletas de secundaria. Sus estudios reconocieron las exigencias físicas, psicológicas y sociales que los estudiantes-atletas enfrentan continuamente en la secundaria. El investigador Moen y otros colegas realizaron un estudio en 2017, donde se centraron en el determinante psicológico que contribuía a este “agotamiento.” Descubrieron que los predictores significativos del agotamiento incluían efectos negativos como la tristeza, la ira, la culpa y la preocupación. En otras palabras, los estudiantes-atletas que experimentaban afecto negativo o preocupación tenían una mayor probabilidad de experimentar agotamiento.

Otro determinante del agotamiento es el factor físico. Las emociones negativas, que pueden variar en gravedad desde la tristeza y la depresión, muestran agotamiento no solo emocional, sino también físico, y corporal. Este agotamiento puede ser resultado de un entrenamiento y una competencia excesivos sin un descanso y una recuperación adecuados. Es más probable que los atletas que sufren lesiones o enfermedades perciban negativamente su rendimiento, lo que puede contribuir al agotamiento.

Los investigadores Raedeke y Smith utilizaron el Cuestionario de Agotamiento Atlético en 2001, y los investigadores Kallus y Kellmann utilizaron el Cuestionario de Equilibrio entre la Recuperación y el Estrés 36 Sport en 2016 para evaluar el agotamiento atlético en atletas. El Cuestionario de Agotamiento Atlético (ABQ) es un instrumento ampliamente utilizado para evaluar el agotamiento atlético. Por otro lado, el Cuestionario 36 Sport es una herramienta que se utiliza para evaluar las percepciones de los atletas sobre el estrés y la recuperación en el contexto del entrenamiento y la competición. Ayuda a monitorizar el equilibrio entre la recuperación y el estrés, identificar posibles estados de subrecuperación e informar sobre las prácticas de entrenamiento y recuperación.

Cada estudiante-atleta tiene una experiencia diferente con el agotamiento, ya que puede manifestarse de distintas maneras. Por lo tanto, al abordar o prevenir el agotamiento, es crucial utilizar un enfoque individualizado para cada estudiante-atleta. Aquí en SRHS, los estudiantes de último año debaten si optar o no por practicar deportes en la universidad, a pesar de sus experiencias con el agotamiento.

CJ Harter, otro estudiante-atleta de SR, jugó fútbol americano durante tres temporadas. En su primer año, jugó en el equipo Junior Varsity, jugó para el equipo Varsity en su segundo año, se saltó el penúltimo año y regresó para jugar en el equipo Varsity en su último año. En su primer año, se dio cuenta de que le interesaba jugar fútbol americano en la universidad. Pero al acercarse el final de su último año, se dio cuenta de la gran dedicación que le demandaría. Para él, era importante elegir una universidad con un excelente nivel académico, pero intentar dedicarse al fútbol americano y equilibrar sus estudios al mismo tiempo habría sido difícil, en su opinión.

Durante su penúltimo año, cuando no jugaba fútbol americano, CJ intentó probar suerte en el béisbol para ser reclutado por un equipo universitario. Creía que si se esforzaba y tenía una buena temporada en su penúltimo año, tendría la oportunidad de ser descubierto. Algunos de los problemas que enfrentó fueron experiencias difíciles con sus compañeros de equipo y, en general, no jugar bien. Cuando comenzó el último año, tomó la decisión de volver a jugar al fútbol y asegurarse de que este año fuera memorable para él.

No dedicarse al béisbol no era el plan ideal que CJ tenía. Se dio cuenta de que ya no amaba el béisbol tanto como de joven. El deporte ya no le proporcionaba la misma alegría. Pero a pesar de estos contratiempos al elegir un deporte, no se arrepiente, ya que ambos le dieron lecciones y le permitieron adquirir experiencias que lo han convertido en la persona que es hoy. Al recordar su penúltimo año, CJ reconoce que experimentó agotamiento. En aquel momento, lo llamó estrés, ya que tenía que compaginar clases y exámenes AP, y al mismo tiempo practicar béisbol durante meses, a pesar de que ya no se divertía.

CJ describe su experiencia con el agotamiento diciendo: «El agotamiento es algo muy real que experimentan muchos atletas. Puede ser especialmente duro porque puede sentirse como una batalla silenciosa con la que uno mismo tiene que lidiar».

Ahora, CJ ha decidido centrarse en sus estudios en lugar de en los deportes. Tuvo largas conversaciones con su padre sobre si debía o no jugar fútbol americano en la universidad, y no fue fácil dejarlo. Su padre y sus entrenadores siempre lo apoyaron muchísimo y estaban dispuestos a ayudarlo, si se lo pedían, con los recursos necesarios para que pudiera dedicarse al atletismo en la universidad. Cuando le preguntaron a CJ si se retractó de su decisión, respondió: “Sí, a veces siento que debería haberme dedicado al fútbol americano en la universidad. Me siento un poco culpable porque creo que podría haberlo hecho, pero siento que mi experiencia universitaria es más importante que los deportes ahora mismo.”

CJ espera ayudar al equipo de fútbol americano, junto con los demás entrenadores, durante el verano. Asistirá a la Escuela de Minas de Colorado, donde se especializará en ingeniería mecánica, con becas académicas. Un consejo que daría a las futuras personas mayores que se encuentren en su misma situación es: «Hagan lo que les dicta el corazón y no se sientan presionados a tomar una decisión. Al final, todo saldrá como debe salir».

Ser fichada y seleccionada para el penúltimo año es una experiencia única para Sophia Everett, jugadora de sóftbol de SR. Fue fichada por la UC-Berkeley en su penúltimo año. Durante los cuatro años de preparatoria, formó parte del equipo universitario de sóftbol.

Sophia empezó a jugar sóftbol a los ocho años. Empezó en ligas recreativas y, al cumplir los diez, empezó a participar en ligas itinerantes. Solía jugar béisbol con los chicos de la primaria y también baloncesto durante el almuerzo. Y a veces, béisbol fuera de la escuela. Sophia no solo jugaba en su equipo de sóftbol, sino también en los equipos de baloncesto y voleibol de SR.

Cuando le preguntaron a Sophia cómo era practicar tres deportes en la preparatoria, dijo: “Es genial. Siento que muchos deportes se trasladan a otros deportes. Por ejemplo, lanzar una pelota en sóftbol es similar a golpearla en voleibol y baloncesto”. Sophia habló sobre sus preocupaciones sobre practicar un deporte competitivo en la universidad. Ella comparte: “La verdad es que estoy muy nerviosa porque me especializaré en [psicología]. Originalmente quería especializarme en administración de empresas, pero sé que ir a Berkeley será una locura, incluso si no fuera a practicar un deporte. Y si intento ir a negocios y practicar un deporte, será difícil y mentalmente desafiante.”

Sophia no sabía que jugaría en el equipo de sóftbol de la UCB. Visitó otros campus, y fue entonces cuando visitó Berkeley, donde describe que la UCB se sintió como en casa. Su familia y amigos la apoyaron mucho. Recibió visitas de familiares, sus amigos la felicitaron y, en general, sus entrenadores estaban muy orgullosos de ella.

Sophia siempre supo que quería jugar en la universidad, pero en su primer año se enfrentó al obstáculo del agotamiento. Después de jugar desde los ocho años, el béisbol en la preparatoria no era lo mismo que jugar en ligas. El béisbol en la preparatoria también requiere un buen desempeño académico, como cualquier otro deporte, si quieres permanecer en un equipo. En su primer año, enfrentó una gran fase de agotamiento. La razón fue que sentía que la presionaban para jugar, que ya no era una elección. Sentía que ya no amaba el deporte.

Aunque quería rendirse, decidió tomarse un descanso de tres meses en su primer año y regresó con más determinación y motivación. Sophia jugará sóftbol en la UCB para la División I de la NCAA, con una beca completa. Jugar en la universidad ha sido su sueño desde pequeña. Un consejo que Sophia da a cualquier estudiante de último año que tenga dificultades para elegir un deporte en la universidad es: “Piensa en los buenos recuerdos que tienes del deporte y pregúntate si esos recuerdos pueden compensar todas las desventajas.”

Los entrenadores pueden ser un recurso valioso para la comunicación, permitiendo a los atletas buscar ayuda cuando luchan contra el agotamiento o dificultades académicas. Aquí en SR, el exdirector atlético José De La Rosa y la entrenadora de fútbol/tenis Nichole Caiocca son reconocidos por el apoyo que brindan a sus atletas.

José De La Rosa (también conocido como JDR) es profesor de educación física, entrenador de JVB y del equipo universitario de fútbol en SR. De La Rosa jugó al fútbol de niño. No jugó en la universidad debido al factor económico que implica jugar en un equipo universitario. Jugó en el FC (Football Club) desde los siete años hasta poco después de la preparatoria. Cuando se graduó de la universidad, el hermano menor de De La Rosa iba a cursar el último año en SR. No le gustaba el estado del programa de fútbol en ese momento, por lo que se comprometió a regresar a SR como entrenador en 2017. Esto lo llevó a convertirse en director atlético durante seis años antes de convertirse en profesor de tiempo completo.

De La Rosa cree que es difícil dedicarse a cualquier deporte. Dice: “De todos los estudiantes que practican deportes en la preparatoria o en deportes juveniles durante su infancia, creo que solo el siete por ciento juega en la universidad en cualquier nivel.”

De La Rosa también cree que los deportes universitarios abarcan más que solo las divisiones superiores. Al igual que jugar en las divisiones superiores, menciona que practicar deportes en los colegios universitarios puede ser mucho más fácil, pero aún hay mucho trabajo detrás, como la elegibilidad. Un estudiante debe ser elegible para la NCAA, pero también académicamente elegible, manteniéndose al día con sus calificaciones.

Afirma: “La gente no se fija en los equipos de División 2 o División 3, piensan que solo es la División 1. Los atletas jóvenes solo ven lo que hay en la televisión y en Instagram. Así que creo que eso disuade a los estudiantes de continuar al nivel profesional. [El deporte] se convierte más en un trabajo, y creo que lo que mucha gente no ve es que hay mucho trabajo detrás de ser reclutado, o incluso jugar en la universidad, ya sea en cualquier nivel.”

Al igual que JDR, Caiocca cree que estar más abierto a las divisiones inferiores brinda más oportunidades de jugar, especialmente después de años de dedicación a un deporte. Ella dice: “Creo que muchos estudiantes atletas han dedicado muchísimo tiempo a su deporte, muchos años buscando el éxito. Creo que realmente necesitas visualizar cómo será tu vida en esa universidad en particular, o si tu vida va a ser sin ese deporte, ¿te parece bien?”

Caiocca es profesora de matemáticas y también entrenadora de fútbol universitario femenino y golf femenino. También colabora con el equipo de golf masculino y el de lacrosse. Pero su principal enfoque es el fútbol femenino, que ha entrenado durante 10 años. Caiocca entrenó en otra escuela antes de comenzar a enseñar en SR. Creció entrenando y ayudando a entrenar, y sus entrenadores personales fueron una gran inspiración en su vida.

Caiocca ha practicado todos los deportes que ha entrenado. Creció jugando al fútbol desde pequeña, jugó en el equipo universitario en la preparatoria, pero decidió no jugar en la universidad de inmediato. Terminó regresando con algunos requisitos de elegibilidad pendientes, así que jugó en el nivel universitario en el JC City College de San Francisco. Después del colegio universitario, Caiocca fue aceptada en el CSB, lo cual para ella era una buena opción académica, pero no tuvo la oportunidad de jugar allí.

Un consejo que Caiocca comparte es: si quieres jugar en la universidad y has cubierto el aspecto académico, hay un lugar ideal para ti. Muchas veces, la gente piensa en las universidades de renombre, pero hay muchas otras opciones. Los estudiantes podrían usar el colegio universitario para transferirse o algunas universidades de la NAIA que no solo salen en televisión; si esa es una opción para ti, ¡genial!, pero también hay muchas otras opciones.

Otra profesora y entrenadora con gran conocimiento sobre los estudiantes que desean practicar deportes en la universidad es Catherine Healy. Healy es profesora de educación física y entrenadora de voleibol femenino de primer año y voleibol masculino de tercer año. También fue entrenadora del equipo femenino de baloncesto universitario aquí en SR.

El primer año de Healy en SR fue en 2002, donde estudiaba para ser profesora de educación física, pero ese mismo año también empezó a entrenar baloncesto. SR necesitaba un entrenador de baloncesto, así que se convirtió en entrenadora del equipo femenino universitario tras ser convencida por otros entrenadores. Healy también jugó baloncesto en la universidad y consideró la posibilidad de convertirse en jugadora profesional. Se presentó a las pruebas para la selección nacional, pero decidió dejarlo alrededor de los 25 años. Considera que el baloncesto es el principal deporte que puede entrenar al más alto nivel.

También empezó a entrenar voleibol cuando su hija asistía a SR. Entrenó a su hija y a sus amigas hasta que todas se graduaron hace dos años. También ha entrenado equipos juveniles, y afirma que entrenar en las categorías inferiores de cualquier deporte brinda a los jóvenes la oportunidad de jugar en la escuela secundaria. En los 23 años que lleva en SR, Healy recuerda a 10 de sus atletas que se hicieron profesionales o practicaron deportes en la universidad, sin incluir a los atletas de la universidad juvenil.

La hija de Healy, Mary Healy, se graduó con la generación de 2023 y actualmente asiste a la Universidad Estatal de Washington, donde juega voleibol en la División I de la NCAA. Healy describe que ahora que sus dos hijos están en la universidad, puede disfrutar del fruto de su trabajo mientras los observa y los apoya. Pero no fue fácil ver a sus hijos donde están ahora. Comenta que el proceso de reclutamiento es despiadado, y la cantidad de dinero que se necesita invertir en el reclutamiento tampoco es fácil.

Cuando Mary Healy estaba en la preparatoria, Healy lo pagó todo. Dice: “Probablemente gasté unos $80,000 en total durante los seis o siete años. Pero ahora, Mary recibe una beca completa, así que es un alivio. Ya no tengo que pagar nada.” En cuanto a su hijo, Jack, no practicaba muchos deportes que implicaran viajar, lo que lo hacía un poco más económico.

Healy ha visto a sus atletas elegir divisiones inferiores para mejorar y equilibrar mejor lo deportivo y lo académico. Ella dice: «Creo que la gente minimiza o no aprecia el hecho de que tienes más posibilidades de encontrar la felicidad y el éxito en las divisiones inferiores que intentando constantemente ser reclutado para la División 1. La División 1 es muy, muy difícil. Es un negocio. Y encontrar un puesto en una plantilla en la División 2, la División 3 o en una NAIA, que es como por debajo de la División 2 o en un colegio universitario, significa que puedes jugar en un equipo de una universidad. Puedes formar parte de algo. Creo que más gente debería considerar las divisiones inferiores».

Un consejo que Healy le daría a cualquier estudiante deportista que tenga dificultades para compaginar sus deportes y su tiempo con los estudios es: “Los deportistas dedican de dos a cuatro horas diarias a su deporte. Nosotros tenemos dos horas semanales en asesoría, aprovecha ese tiempo. No socialices. Ve a algún lugar donde vayas a trabajar y sé productivo. Si tienes un tiempo libre, tienes que aprovecharlo. Si tus profesores no saben que eres un deportista comprometido que hace todo esto después del horario escolar, no podrán entenderte ni entender por lo que estás pasando para ayudarte.”

En cuanto a mi experiencia, personalmente nunca me propuse ser un gran deportista ni tener éxito en ningún deporte. Jugué al fútbol en un equipo pequeño de los 6 a los 10 años, solo porque mi padre me obligó. Pero con el tiempo, aprendí a disfrutarlo. No era necesariamente el mejor, pero tampoco el peor. Era lo suficientemente bueno como para tener minutos de juego y ser titular, pero no lo suficiente como para unirme a un club y forjarme una carrera gracias a ello.

Y me parecía bien.

En mi primer año de preparatoria, sabía que quería practicar un deporte, pero no estaba segura de cuál. Así que recurrí al deporte con el que estaba más familiarizada. Fui a la reunión de fútbol para informarme sobre las pruebas, pero al día siguiente, al escuchar los anuncios de la escuela, me enteré de que el equipo de animadoras también tenía pruebas. Asistí a las pruebas y logré entrar al equipo juvenil.

Mi primer año fue duro. No conocía a mis compañeras y no estaba acostumbrada a llegar a casa sobre las 7 p. m. Me costaba mucho hacer las tareas como estudiante de primer año de preparatoria, y eso me creó malos hábitos. Así que, cuando terminó la primera temporada, comenzó la segunda inmediatamente después, y no estaba segura de si quería seguir animando. Tres años después, en el último año de preparatoria, seguí animando durante los cuatro años.

Cuando llegó el momento de solicitar plaza en la universidad y decidir a dónde quería ir, consideré ser animadora. Eliminaría de mi lista universitaria las universidades que no ofrecían porristas como deporte, pero me enfrenté a la realidad que estaba evitando: el agotamiento. Empecé a considerar si practicar deportes en la universidad era una buena opción. Me di cuenta de que no podía ignorar que ya no era capaz de seguir el deporte que antes amaba, porque la porrista se había convertido en algo que me apasionaba.

No fue fácil darme cuenta de que el agotamiento había afectado mi pasión por la animación. Pero ahora mismo me siento cómoda estudiando en la universidad y dedicando todo mi esfuerzo a obtener buenos resultados académicos. La animación se había convertido en una parte importante de mi identidad, pero debido a eso, parecía que había dejado de lado todo lo demás que me pasaba en la vida.

No hay nada de malo en dejar de lado algo que perseguiste durante años. Es bueno recordar los buenos momentos y aceptar que necesitas encontrar esa pasión en otro lugar. Ya sea practicar el deporte como pasatiempo o descubrir una pasión atlética diferente, como ir al gimnasio o correr largas distancias. Después de todo, participar en el atletismo o en cualquier pasatiempo activo tiene numerosos beneficios, como mejorar el estado de ánimo, desarrollar habilidades para la vida y un sentido de pertenencia a una comunidad.

La animación me enseñó muchas lecciones y me convirtió en la persona que soy hoy. A cualquiera que esté luchando contra el agotamiento, le aconsejaría: “Si estás dispuesto a asumir muchos riesgos y hacer sacrificios, no renuncies a tus objetivos, incluso si es difícil.”