The Canal Overflows With Segregation

January 5, 2022

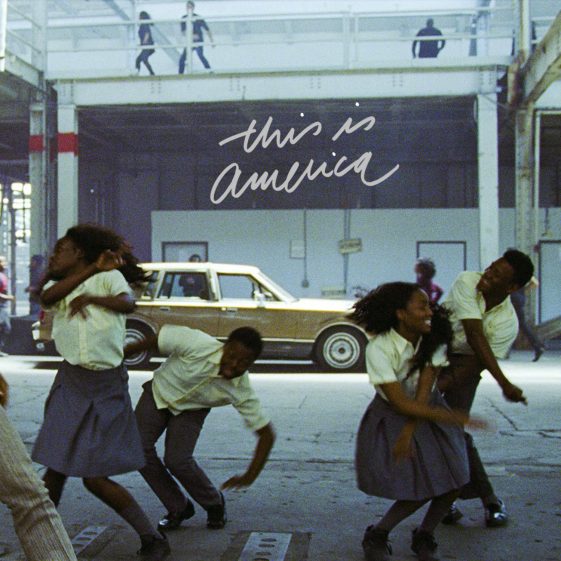

“This is the barrio in the middle of paradise,” said El Flaco in Spanish.

As I rode around Pickleweed park, in the Canal area of San Rafael I encountered El Flaco. El Flaco isn’t his real name, it’s the name he chose for our interview.

El Flaco lay in a grassy piece of land in the corner of the park. His clothes were covered in dust and dried concrete. “I just got off of work,” he told me. Every day he wakes up at 6 am, walks to the bus station, and rides along the freeway all the way to Santa Rosa, Petaluma, or Novato. “I’ve even made it as far up as Ukiah,” he said, delighting me with details of the different types of “operations” he performs, everything from gardening to electricity.

That day he had a masonry job: “It paid well,” he told me.

El Flaco had a mean look on his face. His eyebrows curled down on his eyes. In all honesty, I was scared to approach him when I first saw him resting. He had several tattoos running down his hand. A knife was inked onto one of his fingers. And the way he dressed made me rethink my options.

I was part of the problem that this story is trying to solve.

Apart from his “mean looks” and the fact that he didn’t want his real name to appear in this article, El Flaco was a really nice man.

Like most neighborhoods that have a predominantly immigrant population, the Canal is portrayed as an active warzone by the media, making it a “no go zone” in the collective subconscious of many, if not all San Rafael inhabitants.

But how can this be? In a research done by The US Census Bureau in 2019, Marin County has an average household income of $91,742. Which makes it 40% richer than the rest of California. Surrounded by the beautiful bay and hilly redwood forests. It is hard to imagine an unattractive place in the woodlands. But, the Canal’s big gray streets break the beautiful rhythm. Its tall, gloomy framework gives it an eerie vibe.

The Canal serves as an immigrant gateway. Minorities have cohabited the area since the beginning of the twentieth century.

At first, it served as a destination for Vietnamese immigrants, but it switched to a mostly Latin0 neighborhood around the ’90s. A study was done by Mitchell Crispell, a UC-BerkeleyUC-Berkley master’s student in the Department of City and Regional Planning, pointed out that the Hispanic population has increased from 47% in 1990 to 80% in 2013.

Rows of small studio rooms piled one on top of the other make the apartment complexes look like jail cells. Only separated by thin concrete walls between houses, the tenants can listen to the conversations of their fellow neighbors. Communities pile up inside the rooms. Families of eight, ten, or even twelve people living inside the small apartments.

“I lived in an apartment where 8 people lived. At times we had 15 people living together. People even slept in the kitchen,” said Eduardo Garcia, a former resident of the Canal.

It is no surprise that the area of Canal is considered to be the most racially segregated neighborhood in Marin County. The Marin IJ, SF Chronicle, and Mercury News have written articles about the topic, and with good reason. For more than two decades people of the canal have been victims of racial profiling, racism, minimum governmental support, etc.

“There are no written policies, but the system is molded majorly based on racial hierarchy,” said Samir Gambhir, the Director of the Equity Metrics Program at the Othering and Belonging Institute, when asked what the factors that expand racial segregation were.

“The options are limited when you are an immigrant living in the Canal. Rent is overpriced, since you don’t have a social security number you can’t get any good financial support from the government, sometimes all you can do is rely on the free food coupons that are given out by Canal Alliance or the places where they give out meals,” said Eduardo Garcia.

When asked what he thought the root of the problem was, Mr. Eduardo said: “I didn’t go to school, I had to work, maybe that’s it.”

Mr. Eduardo is partly right, living in a segregated community does influence your opportunities of having a higher education. As Mr. Gambhir said: “The harm is that people living in segregated communities end up having fewer resources. No school funds equal no education.”

Housing plays a critical role. With houses being in a median sale price of $1,325,000, the people that live in Canal have a minute chance of owning a house with their minimum wage salaries. This is where generational wealth plays its part. Stated simply, people who inherit generational wealth have a significant financial advantage over those who don’t.

And this aspect is where the Canal neighborhood drowns in problems. Thanks to a history of redlining, the area has become the only place where people that don’t earn enough money to rent in a predominantly white neighborhood or buy a house live in. Generations of immigrant families struggle to make ends meet and are forced to leave school after high school in order to at least be able to put food on the table and have a roof over their heads.

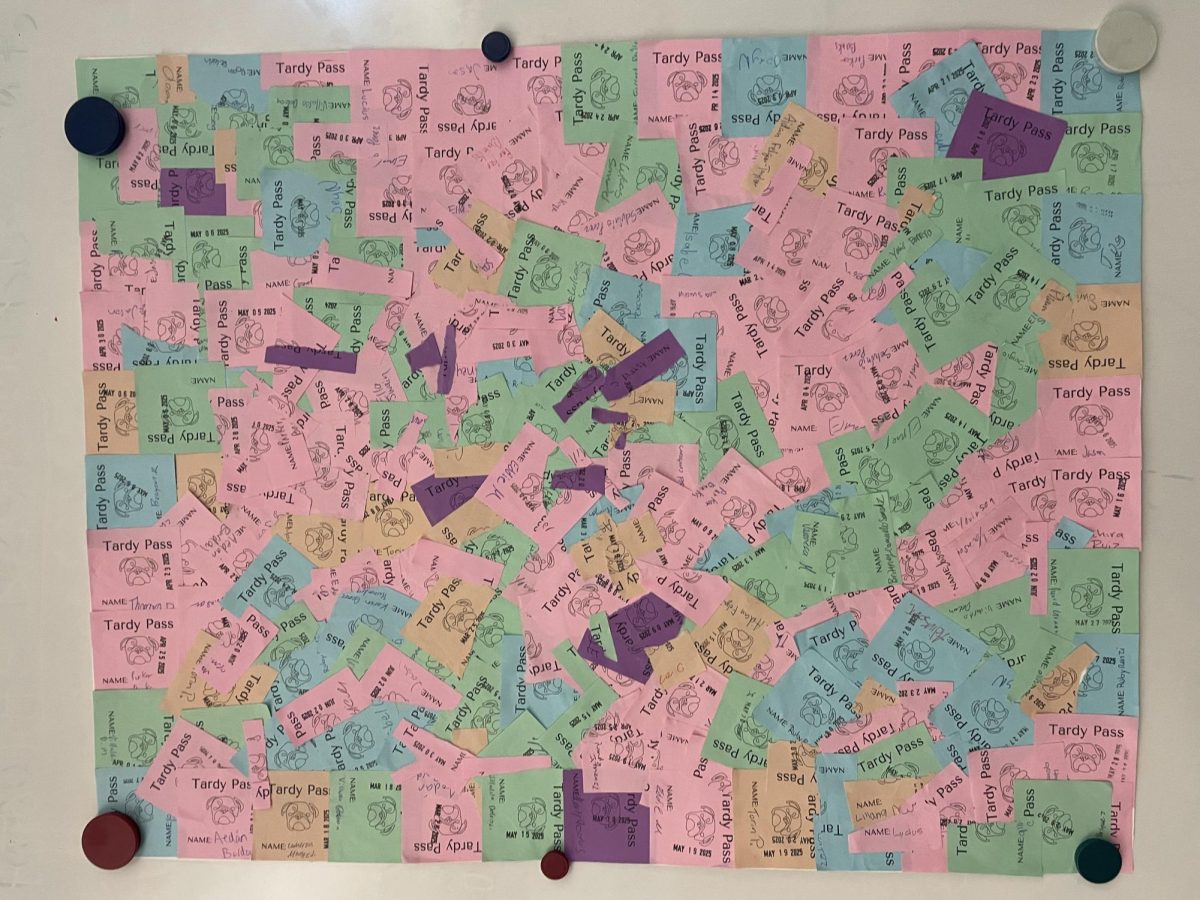

The student body of San Rafael is predominantly Latino (66%); most of the students live in the Canal. These students struggle with having to take care of their small siblings, working after school to afford simple necessities.

“Getting home is tough sometimes,” said Elmer Montepeque, a resident of the Canal and SRHS alumni.

The problems we face as a society need to be attacked from the roots. As long as policies and systemic harassment keep putting people down, neither charity nor small social efforts will amount to making a difference.