Should We Still be Teaching To Kill a Mockingbird?

December 9, 2022

I was thirteen, a freshman, young and immature, when I read Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird in my high school English class. At face value, the book can be seen as an overview of racial injustice in the deep South. The book is taught in high schools across the United States, usually 9th grade classrooms and is often used as a platform to discuss racial injustice.

The novel is engaging, but many themes in the book are oversimplified by teachers to fit the 9th grade curriculum – the messages are inadequate for the needs of our country today. For these reasons, To Kill a Mockingbird should not be taught in high school.

The 281 pages of this 1961 Pulitzer Prize winner are told from the perspective of a 6-year-old white girl, Scout Finch. She lives with her lawyer father, Atticus Finch, and her younger brother Jem in the sleepy town of Maycomb, Alabama. The story takes places around 1933 when a young black man, Tom Robinson, is accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a white woman. Atticus is appointed to defend Robinson. The jury convicts Tom of being guilty and he is later shot trying to escape prison.

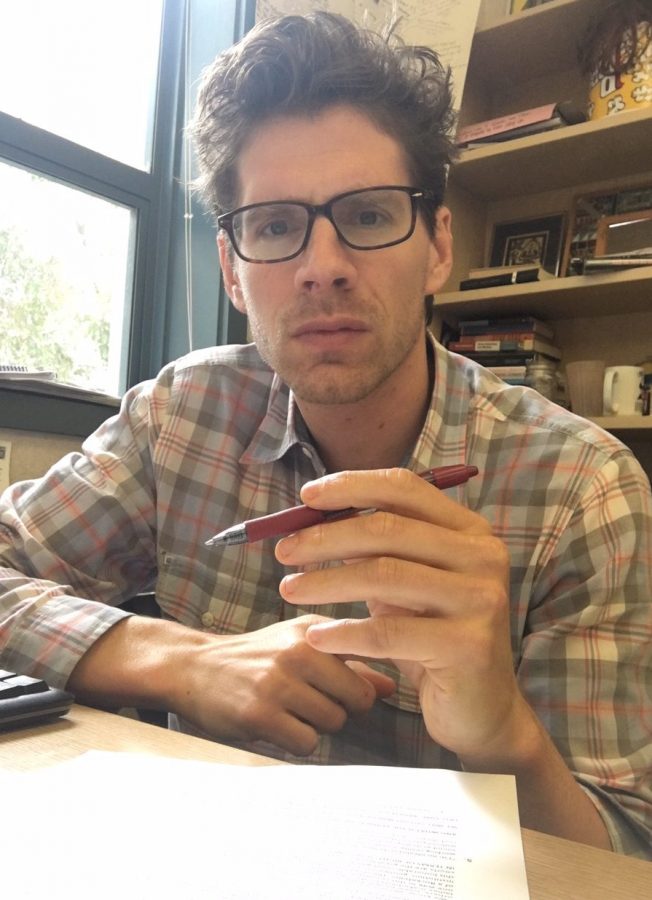

One of the prominent issues with the book is that it feeds into the narrative of the “white savior,” portraying people of color, black people specifically in this case, as helpless and unable to stand up for themselves. In most classrooms across the country, Atticus is discussed as this savior character. Mr. Simenstad, a San Rafael High School English teacher of 23 years, describes how the book suggests that “if you’re a white person who stands up for less fortunate brown people or people of color, that’s enough.” The book can not be taught through one lens. Meaning if you are going to discuss Atticus you must address all of his qualities, not just what makes him a hero.

Sure, you can talk about the obvious inequality and abuse Tom Robinson faces because of the racist mob mentality of the South in that period. You can use it to teach kids about the systemic racism people of color face even today. However, white characters are at the heart of To Kill a Mockingbird, specifically Scout, who gains personal growth from witnessing a black person’s struggle with prejudice and racism. The focus is ultimately on Scout, not what Tom Robinson experiences.

The book can be taught, undoubtedly, but not to thirteen and fourteen-year-olds who haven’t even learned about the Civil War. It requires a careful approach and a mature audience. It requires you to discuss why the book and characters are flawed and about those flaws. To effectively teach this book, the characters can’t be simplified.

An example of this is Atticus Finch and his role as a father and a lawyer. In many classes Atticus is named a literary hero. He does a brave thing standing up for Tom Robinson but at the end of the day he was just doing his job. 1933 in the South was a time flooded with racial aggression. When Atticus was assigned Robinson’s case he wasn’t making a stand against racism or advocating for racial equality, he was just doing his job. In fact, he never really says he’s against racism at all. He just dismisses it as a shortcoming of society, something out of his control. In reality, Atticus was a white man in a position of power who could make change, but he never did. In Chapter 16, he talks with Scout about Mr. Cunningham, an outwardly racist character in the book, saying, “He just has blind spots along with the rest of us.”

This discussion usually isn’t brought up in a classroom full of high schoolers.

SRHS does not teach To Kill a Mockingbird anymore. After my freshman year (2019) many teachers took it out of their curriculum.

So, if you are looking for a book to teach in a high school classroom that talks about generational systemic trauma people of color face, To Kill a Mockingbird is not for you. There are many alternatives like Yaa Gyasi’s Homegoing. This historical novel is about two half sisters. Effia who marries a wealthy Englishman and Esi who is captured and sold into slavery. The book traces the two different descendants of the sisters. In the words of Ms. Levy, a San Rafael High School English teacher, “It shows that, generational trauma, it starts in Africa and then it comes to the United States… you see the damage and how it gets passed down, To Kill a Mockingbird doesn’t do that.”

Homegoing shows a timeline of the harm and effect of generational racism, whereas To Kill a Mockingbird briefly touches on the hardship, consistently bringing the attention back to the white characters. You can see this specifically when the book reveals that Tom Robinson was shot 17 times trying to escape prison. Before the reader can process this tragic moment, all of the attention is brought back to the white characters as Scout and Jem are almost murdered at the end of the book. So again, why would we teach a book that places racism at the bottom of the priority list, as a platform to talk about racial injustice and prejudice?

To Kill a Mockingbird is an engaging coming-of-age story at best. Teaching the book without discussing any of its shortcomings is harmful and leaves students with the wrong impression about racism, what it looked like in that period and how it continues today.

AYEEE • May 21, 2025 at 5:17 am

This was so good!!!! We read this in class after finishing the book and I couldn’t agree more!!!

Support from NC

Bill Allan • Feb 14, 2023 at 8:38 am

I wasn’t convinced at the start pf this article, but I was by the end. That’s effective journalism.

Glenn Dennis • Jan 27, 2023 at 2:20 pm

Hi Jade,

Hi Jade. Mr. Dennis here. Your article is spot-on and insightful. My son had to read TKAM in his 9th-grade English class. He found the story dated and the hero, Atticus Finch, problematic. He suggests that a modern generation of youth should read Ta Nehisi Coates, Between the World and Me. He thinks it would be more relevant and engaging as it addresses contemporary challenges African-Americans face in the United States. It’s powerful, passionate and elegant. I hope your senior year is going well. Say hello to your family.