Saying Goodbye to the Boy with Boobs

June 9, 2023

“Hey, what’s that on your shirt?”

I’m standing among a group of students at the dorm where I’ve been assigned to stay during Stanford’s admitted students weekend. I met most of them earlier at lunch, including the guy who just asked me about the name tag I’m wearing.

“It’s just something I picked up at the queer student mixer before this,” I say quietly, trying to be casual.

I had completely forgotten about the name tag on my shirt, my name and pronouns scrawled across it in faded blue ink. Back in a room full of other queer and trans people, it had felt completely innocuous. It was standard-practice, something I’d done a thousand times before in similar spaces.

Now, however, it felt like a target. One that I had put right on my chest for everyone to see.

“Oh. Cool,” replies the guy. Except it’s not cool, because everyone has suddenly gone quiet, and I can see the gears spinning in his head. After a painfully long pause, he asks another question: “By the way, what are your pronouns?”

My heart sinks. He doesn’t ask anyone else.

Just me.

At this point, everyone else has trained their eyes on me. They’re all waiting for a response. My cheeks feel warm as I answer, “I use he/him pronouns.”

Another awkward silence. Eventually, the conversation stutters back to life, but I’m too distracted to engage again. My gut is in a tight knot, a mess of feelings tangled together. First I feel caught off-guard, ashamed and humiliated. Soon, I start to feel frustrated and angry.

I’ve already had several conversations with this guy. He didn’t have any problems with my pronouns before. Why did he suddenly feel the need to ask? Why did he assume I’m transgender instead of just thinking I’m a queer guy? Why did he have to call me out in front of a bunch of other people?

Of course, it is best practice to ask for other people’s pronouns instead of just assuming. It’s a simple, yet important way to be an ally to trans people. But there is a time and a place to do so, and it is not by singling someone out hours after you first meet them.

There’s a word for when a transgender person is identified as trans while they are trying to pass as cisgender. It’s called being clocked.

Clocked. I’m hesitant to even use the word to describe my experience. It implies that my goal is to pass as cis, and that to do so I need to hide my transness. I’m never trying to hide anything. I’m simply trying to express myself authentically.

I’m a boy. Just like any other boy, I want people to see me for who I am.

I attended two admitted students weekends: one at Stanford and one at Harvard. These weekends were the full extent of my college touring experience. I hadn’t wanted to tour anywhere until I knew where I’d gotten it. I figured there was no use getting excited about places I might not even be able to go to. I had know idea that I would get in where I did.

The name tag incident was an outlier compared to the rest of my experience. At both schools, the people I met mostly just assumed I was a guy. No one seemed off-put or confused by my appearance. No one had to ask me for my pronouns. No one called me “she.”

I’m not used to people treating me this way, something that I can attribute, in large part, to having recently embarked on the journey of medical transition.

In November, I began taking testosterone. In January, I received gender-affirming top surgery. Now not only is my presentation in line with my gender, my body is starting to reflect it as well.

Most people don’t really understand what transition actually is. I know because since I began mine, I’ve received countless questions or concerns and sat through many an uncomfortable conversation.

People imagine transition as checking a few boxes off of a list, and voila! You’ve suddenly changed genders. In reality, it is not nearly as quick, easy, or linear as that.

Transition is an ongoing and constantly shifting process. The goal is to feel more aligned with your gender. This doesn’t look the same for everyone. Each person transitions in whatever way is best for them.

I am not transitioning to become a boy; I’ve always been one. I’m transitioning so that other people will see me that way too.

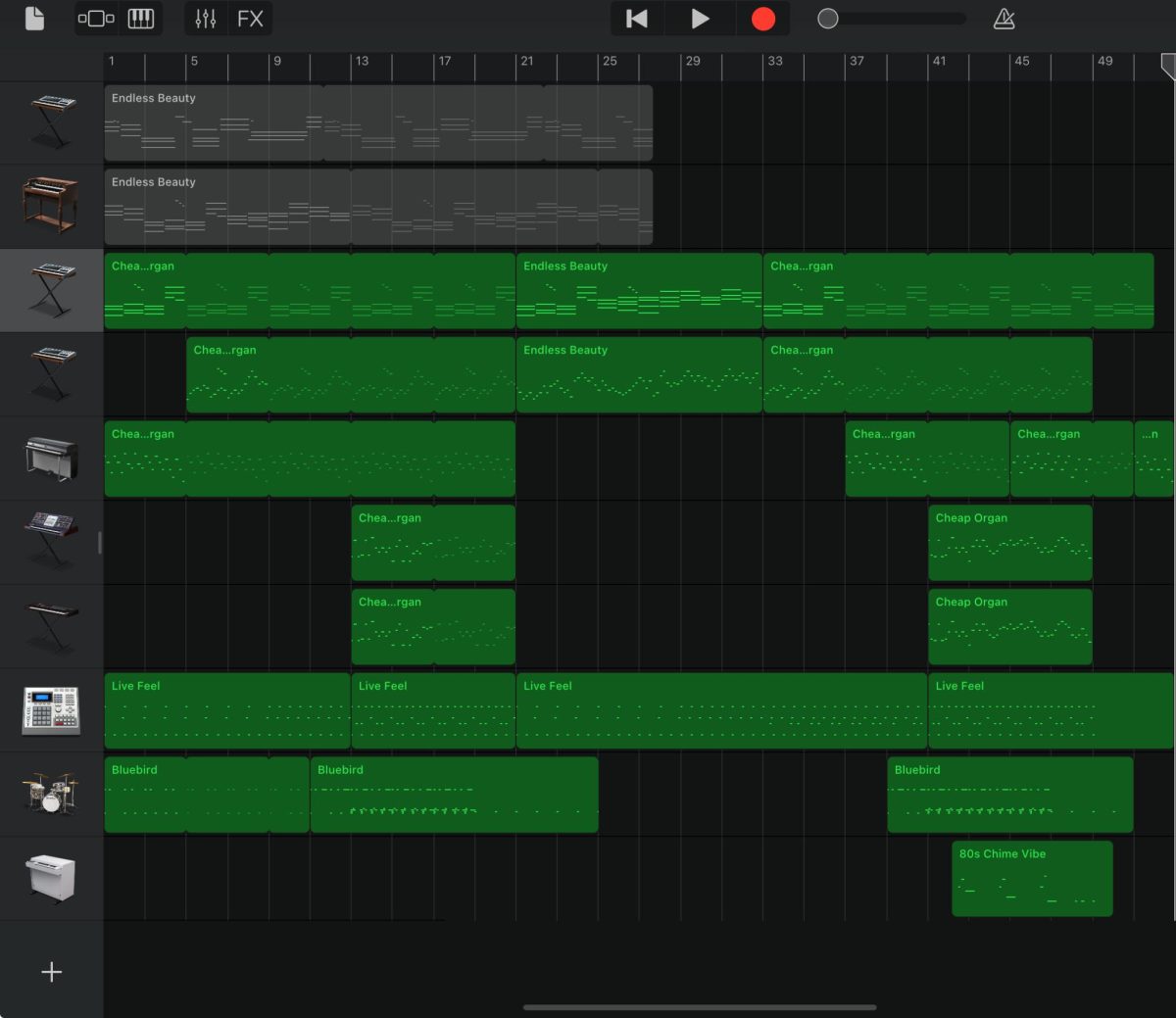

Once a week, for the last seven months, I have injected testosterone (or T as it is colloquially referred to among trans people) into the subcutaneous fat on my stomach. When you’re my age, old enough to start T but not yet a legal adult, they start you on a low dosage.

It’s not like I took my first injection and woke up the next day with hair all over my body and a voice down to Antarctica. The effects of testosterone have come slowly, sometimes painfully so.

The first thing that was different was the hair. Dark, coarse hairs growing in on my legs. A dusting of light brown across my upper lip. Blonde fuzz, nearly invisible, on my chin. Two light patches on either side of my stomach, in the places where I alternate weekly injections.

My voice didn’t noticeably drop until roughly the three-month mark. Slowly but surely, however, it’s becoming noticeably deeper. At least enough for people to not recognize me right away when I call on the phone or to ask me if I have a cold.

My skin is oilier now. My sweat smells worse. I have more pimples. I’ve always been a clean person, but keeping up with my hygiene has become especially important since starting T.

I find myself crying less (something that is common, at least according to the trans corner of Reddit). My mood swings more, though it’s hard to tell if that is the testosterone or the proximity to graduation and the end of my childhood.

Top surgery felt much more immediate than testosterone, in the sense that I woke up one morning with double d’s, and by the end of the day my chest was flat. But the process involved more than just that.

My first appointment for surgery was in July of 2022, at which point I was placed on a 9-12 month waiting list. The only reason I got a surgery date sooner was because someone else had a cancellation.

The hardest part of surgery came after the actual procedure, a double incision or bilateral mastectomy with nipple grafts in my case. I spent the first week resting at home in a narcotics-fueled daze. I couldn’t take off my bindings. I couldn’t shower. I couldn’t hold more than 5 pounds.

Though I could see and feel how flat my chest was, a small part of me was secretly afraid that my boobs were still hiding somewhere under the bandages. I was terrified that when I finally unwrapped my chest it wouldn’t look the way I had been dreaming it would.

These fears were erased when I got my bindings taken off. As excited as I was about my new chest (and getting to shower again), I still had to wear a compression binder for another two months. I also received a thorough care regimen for my scars and nipple grafts.

When I returned to school after two weeks, I couldn’t hold much weight or wear a backpack. I had to reduce my supplies to a chromebook and a few papers, which I ferried around in a tote bag clutched to my chest.

Now I can carry as much weight as I want again, but I can’t lift my arms above shoulder level until July. This is supposed to keep the scars from stretching. I also apply silicone gel to the scars twice daily to reduce their redness, something I’ll continue for another year or so.

Gender-affirming care for trans people has become hotly debated and highly politicized. Across America there has been a record amount of anti-trans legislation, with 556 bills proposed in 2023 alone so far. Many of these laws restrict or entirely ban gender-affirming care. Many are targeted specifically at youth. Youth like me.

People in my life have expressed skepticism towards my medical transition. My parents get questions like “But isn’t he so young?” and “Don’t you worry that he’ll regret it?”

My parents don’t share these concerns. When I was three years old, I explained to them that I was a “boy-girl”. I dressed up as Mr. Incredible for Halloween and asked for a Spiderman bike for Christmas. At Easter I wore a sweater vest to church instead of a dress. I told people that when I grew up, I was going to be Jimmy Page.

Throughout my childhood I never quite fit in with other girls my age, and I often expressed a desire to present more masculinely. Suffice to say, it was not a huge surprise to my parents when I came out. Instead, it was like I’d handed them the final piece to a puzzle that I had been building for a long time.

My parents tell people that they weren’t afraid to let me medically transition. They weren’t afraid because since I came out, they have seen me light up in a way I never did before. They have seen my mental health radically improve. They have seen me become more socially engaged. They have seen me blossom into a capable, confident, and happy person.

They weren’t afraid because they know that medical transition has brought me closer to living as the person I was meant to be.

I’m immensely lucky to have parents who have supported and embraced me so fiercely, who have helped me every step of the way. I’m so lucky to live in a place where I have access to gender affirming care.

In many states, my endocrinologist would go to jail for prescribing me testosterone and my parents would be labeled child abusers for supporting my transition, despite the fact that gender-affirming care is a medical best practice. It is also proven to be life-saving for trans youth, who are at an extremely high risk for suicide compared to their cisgender peers.

No one cares when a 16 or 17 year old gets a nose job or a breast augmentation. But when I get top surgery it’s demonized as mutilation and child abuse. Why can a cisgender person use plastic surgery to feel more comfortable in their body, but a transgender person cannot?

Having access to medical transition and gender-affirming care has dramatically improved my life. I no longer cringe when I see myself in the mirror. I no longer have to go all day wearing a tight binder in order to appear more masculine. I no longer dread getting dressed in the morning or meeting new people. I am no longer afraid to go swimming at the beach. I no longer need to distance myself from everything feminine out of fear that people will mistake me for a girl.

My admitted students weekends reminded me how much I have changed this year. They opened my eyes to the possibilities that medical transition has provided me.

At home in San Rafael, everyone knows I’m trans. I came out at the beginning of my junior year of high school. Many of my classmates I’ve known since middle school, and some I’ve even known since kindergarten.

The people that I regularly interact with almost all remember me from before my transition. Even those who don’t still remember me from last semester, when I had double d’s. When you have boobs, people don’t think of you as a boy with boobs, they think of you as a girl.

Here I have felt incredibly visible as a trans person. My transition has been something for public consumption, it’s something I have had to be incredibly open about. And no matter how much the people around me recognize and accept my identity, to them I will always be a trans man first, instead of just a man.

However, when I was away at admitted students weekends, no one I met knew me for the person I used to be. When they looked at me, all they saw was a guy with a pube-stache and a flat chest. My masculinity was not something precarious, something I had to prove. They just saw me right off-the-bat as a man.

Next year I’ll be going to Harvard. Knowing that I get to be seen as myself in college is immensely freeing. It’s part of the reason I was so determined to start hormones and get top surgery this year. I didn’t want to begin the next chapter of my life tied down by others’ perceptions of me based on the way my body looks.

But there is still the name tag incident of it all. Though at first glance I look like any other man, my transness is an important part of who I am, and it’s bound to come up at some point. I don’t want to feel like I have to hide who I am. But when do I have the “I’m trans” conversation with people?

I’m coming from an environment where my transness is an undeniable fact of life. I’m not used to having to come out to people because I don’t have a choice. Everyone just knows.

Now I have that option, but I have no idea how to approach it. I want to be open and honest with people. I want to live authentically. But is it inauthentic to not tell people that I’m trans right away? Is it inauthentic to just present as a man and not elaborate more?

Why shouldn’t I? After all, it isn’t lying to just be myself. I don’t owe anyone an explanation of my identity if I don’t want to give it.

I don’t want my transness to always be the first thing that people want to see about me. I want people to see me outside of that one aspect of my identity. And yet, I want to be able to immerse myself in queer spaces. I want to be able to be a passionate and active advocate for my community.

I don’t know how to do both at once. I’m facing a completely new problem that I don’t know how to navigate. Part of me feels lost and a little helpless. Another part feels angry that I even have to think about this. That for the rest of my life I will constantly have to decide who to come out to and when or how to do it.

College is a chance for everyone to reinvent themselves. As a trans person, this prospect is especially exciting, but it also comes with a lot of extra baggage that my cisgender counterparts don’t have to deal with. The reality is that I will never get to have a “normal” college experience in the same way that they get to.

While my cis peers will be worrying about which shirts or shoes to take to college, I’ll also have to worry about how I am going to transport a several month supply of testosterone to school because staying on my parent’s healthcare plan in California is much more affordable than purchasing university healthcare.

While my cis peers get to pursue relationships and fall in love freely, I’ll always have to worry about disclosing my identity to potential partners, who may not even be attracted to trans men. I can’t just take someone back to my dorm without giving them details about my body; not because I want to, but because trans people have been killed for failing to do so.

Deciding whether or not to come out isn’t always an issue of preference, sometimes it is one of safety, which doesn’t make things any easier.

The end of senior year is wrought with emotions no matter who you are. Excitement about what is to come. Fear about leaving what you know behind. It has been overwhelming to manage all of this while also navigating the new and complex emotions surrounding my transition.

My transness is an ever-present footnote in the story of my life. Though I always try to find the beauty and positivity in my identity, it can be challenging at times.

My body doesn’t look the way society says a man’s body should look. My stomach is rounder, my hips are wider, and my genitals don’t match. Even my 11-year-old cousin is taller and bigger than me. His mustache is darker too.

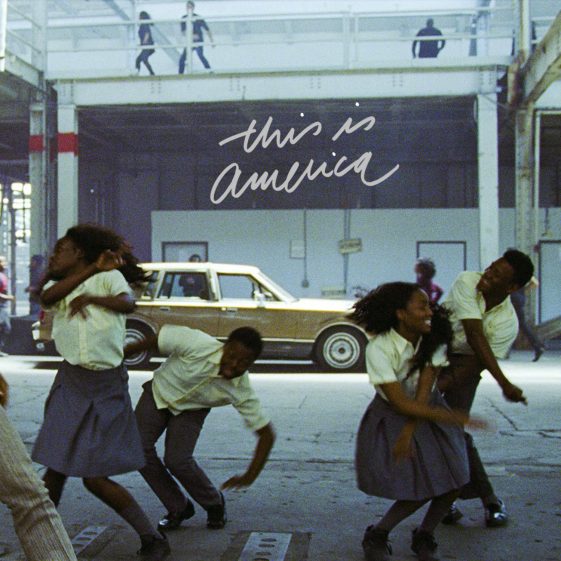

My body is misunderstood. It’s not what most people would call perfect. It’s probably not even what most people would call beautiful. I haven’t seen many representations of bodies like mine, let alone positive ones. That is something I want to change.

My body is transforming. I love it because everyday it’s getting closer to a body that feels like mine.

I’m not the boy with boobs anymore. But that’s okay. Saying goodbye to him means I get to meet the person that he has become.

I’m excited to meet this person. He gets to go to Harvard. He gets to move across the country and embark on a new adventure. It will be hard for him, but it will also be so rewarding. And I know that he is going to do amazing things.

Nick Service • Jun 13, 2023 at 12:21 am

An excellent article – clear and well written, informative and inspiring. Matteo has answered many questions, and has posed important ones for the future of all of us. Everyone has their own, personal secrets; how they feel and think about those around them, their personal desires and fears. How they handle and share (or not) these ‘secrets’ demonstrates that person’s level of maturity and self-confidence. Mateo is clearly an intelligent and mature young man.