Kenneth Jackson, known to me as Mr. Jackson, sits across from me in a faded orange Princeton baseball cap, blue polo with Ray-Bans at the ready, and blue eyes with light in them. He’s brought with him a black Leuchtturm 1917 notebook along with two books. One, he tells me, is on Ancient Greek philosophy. The other is his daughter Dr. Kassi Miller’s scientific work on “short time” (which is the evolution of units of measurable time, over time).

A Sense of Wonder: Mr. Jackson’s Approach To Teaching

I first met Mr. Jackson at Coleman Elementary School in 2016, when I was in fifth grade. He took a unique approach to teaching, showing us how to operate a technical illustration watercolor brush, reciting and animating the Iliad and Odyssey, and introducing the class to microscopes. He went above and beyond the basic curriculum, which he describes as a set of targets whose primary goal is to build upon one another.

“You can teach from that and cover all the bases–but there is more to it than that. There is a sense of wonder, a sense of magic, a sense of poetry, a sense of ‘I never knew that! I am so amazed!,’ and that’s the part I’d like to bring to kids,” he said.

Immediately upon receiving his teaching credential, Mr. Jackson sought out Coleman Elementary School, a school of around 400 located North of downtown San Rafael. Coleman stands out in the school district for being a demographic middle ground (50% Latino, 50% white). The culture is one of learning, creativity, and collaboration–facilitated by colorful murals strewn across campus, mixed media art classes, and niche lunchtime sports (gaga ball, tetherball, four-square, handball, kickball, and ultimate frisbee).

Up until his retirement a year and a half ago, Mr. Jackson taught full-time at Coleman for 20 years. While being a grade-specific teacher, he also developed the STEM curriculum and became (and continues to be) a math coach.

Cayman Stein, one of his 5th grade students in 2016, said: “I remember a big thing for me was how he incorporated his passions into his teaching, like telling stories and talking about his family. He really showed that he enjoyed what he did. I feel like I knew him outside of him being a teacher.”

“He was clearly very smart. I feel like every time I asked a question, he would not only answer, but elaborate and tie it to other things,” said Cayman, who is now a senior at The Branson School. This is something that was apparent in my interview. Mr. Jackson would seem to diverge on an unrelated tangent, and then it would wrap back to the original question. He’s big on using anecdotes and stories to effectively express his thoughts.

“He was very charismatic. He didn’t get hot headed easily, he didn’t raise his voice as most teachers do, he was truly trying to understand where you were coming from,” Cayman added.

How Advertising “Rides The Dark Horse”

He ties his approach to teaching back to his past life as an illustrator in advertising. In Los Angeles 30 years ago, he was creating illustrations for newspapers, storyboarding films, and working on theater set design. Being in illustration for so long required Mr. Jackson to change with the industry as technology took over.

“When I first started as an illustrator, I had a staff of 3 or 4 who worked under me, and we had typesetters and color separators and a mini economy of people. By the time I left, illustration was gone. It was all being done photographically–so I learned that side of it.”

He says that, like teaching, “the inherent object of advertising is to persuade people in order to do something they didn’t know they wanted to do.” He smiles. “This is where Classics comes in.”

Mr. Jackson is incredibly knowledgeable about Classics, which is the study of ancient societies and their influence on the present. He references a famous Alfred North Whitehead quote: “First there was Plato and then there was Aristotle and everything since has just been a footnote.” Plato, Aristotle, and Homer are all creators of ancient Greek and Latin works of literature and philosophy.

At this point in our interview, Mr. Jackson goes off on a long tangent about Plato, which seems to have nothing to do with advertising and teaching. He does warn me, though, that “most of Plato’s students went on to become oligarchic fascists, so you have to be a little bit careful.”

He explains to me something called the Phaedrus, Plato’s only dialogue, a collection of stories featuring his protagonist, Socrates (a real historical figure whose character Plato adjusts in the Phaedrus). Mr. Jackson tells me that “it’s not that [the Phaedrus] is true in a literal sense, but there’s something true about it at the core.”

Plato’s work establishes the ‘myth of the charioteer’, which describes the human soul as a chariot pulled by a light horse and a dark horse together. The dark horse is mortal, emotional, prideful and impulsive; the light one is immortal, temperate, and obedient of the charioteer. The chariot is flown by a charioteer attempting to steer it, operating with the knowledge of how the soul fits together.

Clearly Mr. Jackson is the charioteer of this conversation, because soon the myth connects back to the progression of his life story.

“Advertising relies more heavily on the dark horse. You do not persuade people by logic, reasoning or evidence. Plato says, and I tend to agree based on my experience, that you try and get them angry, you try and get them happy. If you can activate emotion then you don’t have to have the best argument. If you can get people afraid of something–you’ve got them.”

Mr. Jackson has played the role of the charioteer in illustrating, but also in teaching. Mr. Jackson, as a teacher, is a storyteller. It’s evident in his response to any question you ask him and the way he responds in metaphors, contextualizing everything in history. He teaches by way of ancient myths and personal anecdotes.

“Even if you’re teaching something like math, if you have an interesting biographical story about the math concept or the question somebody started with, what the state of the world was, and how they managed to work outside of their own point of view to come to this new different point of view, all of that’s really valuable,” Mr. Jackson said.

I recall him telling the story of Archimedes’ run through the streets of Syracuse, shouting out ‘Eureka!’ as Archimedes did after discovering buoyancy. He would section off ten minutes of class to storytell the Iliad or Odyssey and entertained us with true stories from his childhood in Germany, including his adventures by waterfalls, losing his father’s pocket watch, and running from bears.

Where Mr. Jackson got his “Weltanschauung”

There’s a German word, “weltanschauung,” meaning a worldview that is invisible to the viewer themself. Mr. Jackson attributes much of his weltanschauung to being raised outside of the United States, which changed his perception of America, where he now lives permanently.

His mother, Loise Charlotte Jackson, became a Navy nurse straight out of high school. After the war, she transitioned from being a 1950s housewife to earning higher education and becoming a naturalist, docent, and teacher. She changed along with society, which was beginning to open up to the idea of women in the workplace. Mr. Jackson recalls that “it was considered patriotic that you would fire a woman to open a job up for a returning man.”

His father, Donald Jackson, came from a long line of military men. Donald’s father was the head of the California National Guard during WWI. Towards the end of WWII, Donald Jackson became a pilot, but because the need for pilots was dwindling, he spent much of his time in charge of the police force in Central Germany. His main concern was overseeing the implementation of the Marshall Plan, the US’ initiative to use American dollars to rebuild the economies of Western Europe. “There was a very mixed feeling among German citizens, because they were in a war with the United States, an enemy, and yet here they were trying to help reconstruct the economy for them.”

Germany acted as a “home base” for the Jacksons. Though they traveled to military bases around the world, occasionally stopping to visit relatives in America, they always returned to Berlin. Because of this, he was searching for evidence of what life in the United States was like through the media. He said to me with a laugh, “There was a period where I thought that everyone in California surfed.”

The Opening of the Mind

He began to take up an interest in American history and the guts of democracy–how it began in the Athenian courts, how it traveled across oceans and dictatorships and through centuries, morphing into its twisted modern form. He describes American democracy to me as a grand experiment, one that has tendencies to become closed off, to isolate, to narrow the arteries of free speech with the plaque of obstinance.

“That’s not my upbringing,” he said. “I was always living in someone else’s culture, so I had a lot of admiration and love for lots of different places and situations. What’s necessary in a democratic society is to bring in forms of thinking that you aren’t necessarily going to agree with, but with which you will find some overlap: a sense of common humanity and generosity, as opposed to isolating yourself.”

“He has always stressed the multiplicity of perspectives. He was never the sort of father to indoctrinate and say ‘this is the way the world is,’” said Mr. Jackson’s daughter, Dr. Kassi Miller. She says that one of the most important things she’s learned from her father is how to seek out the value in others.

“One thing that you learn is that people are alike in a lot of ways. People love their children, they want security in their lives, in an emergency they feel a strong sense of community and do things they wouldn’t do in their daily lives,” he said.

Dr. Miller echoed this almost exactly, without prompting, saying: “For my dad, and for myself, a lot of what allows such disparate things to be connected is humanity. We are the ones constructing the mental models, the ideologies, the frameworks through which we, as humans, approach the various things in the world. We aren’t that great at compartmentalizing–it all connects.”

Mr. Jackson describes the relationship between art, science, music, and philosophy over the course of time as a kind of conversation, in which learning about one reveals new facets of the other. “There’s tension and reinforcement at all those levels,” he said.

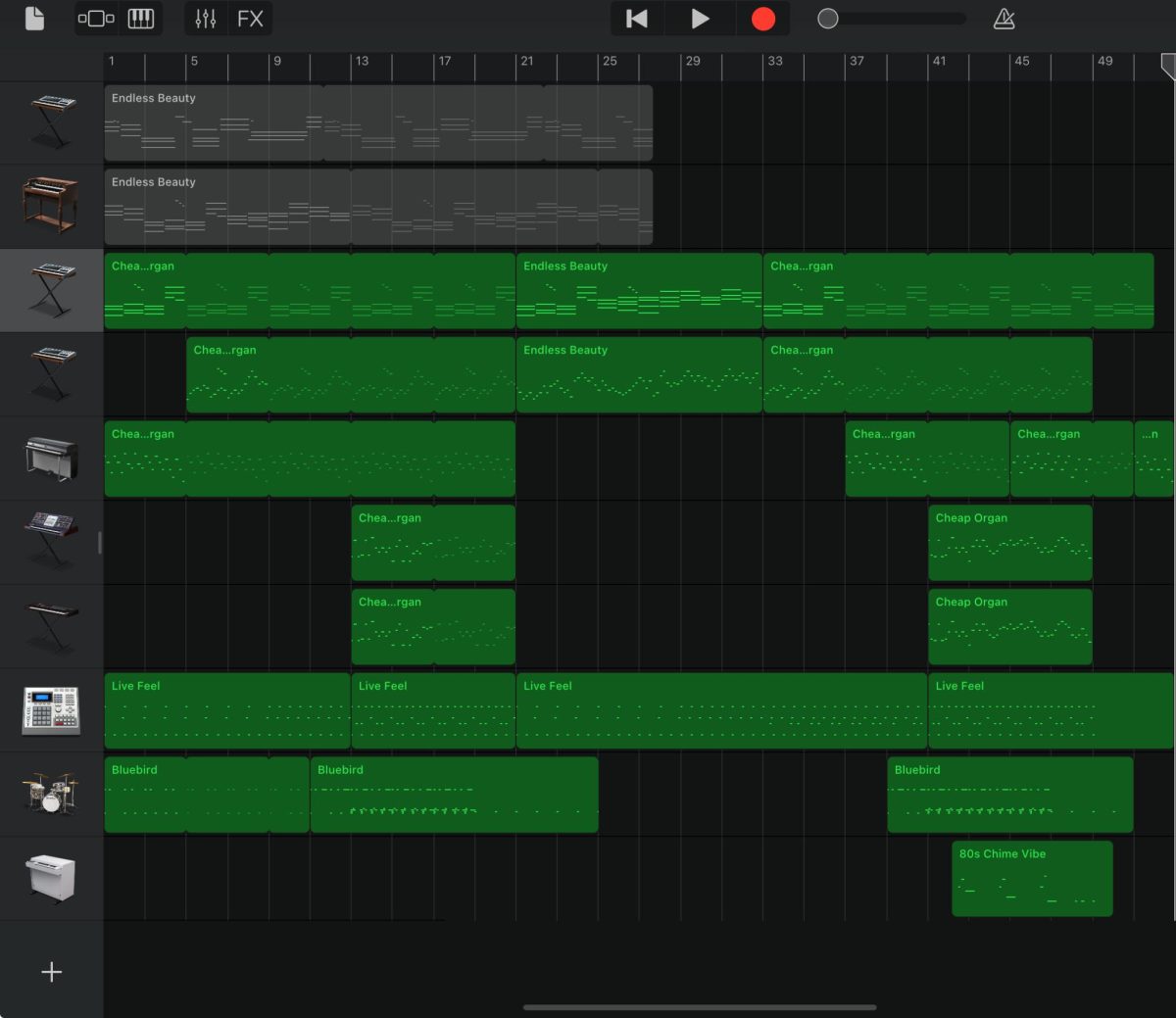

Reinforcing Mr. Jackson’s artistic talents is his capacity for music. He specializes in the music of the 1600s and 1700s and plays a variety of woodwind instruments.

“I play baroque woodwind instruments… that’s a whole world of its own. It’s a true subculture. No amount of time is enough to master it,” he said. Mr. Jackson’s wife is a professor at Cal who conducts and performs with the San Francisco Opera.

Dr. Miller On Her Dad

Over the phone, Dr. Miller is enthusiastic and well-spoken. She shares patterns of speech with Mr. Jackson and frequently uses the words “kind of,” as he does. Dr. Miller tells me that one thing she’s learned from him is the importance of not only having ideas, but expressing them clearly and making sure your words match what you mean.

She describes her dad as someone who’s wonderful and inspiring to be around and is able to brighten up a room with his love of learning, humor, and ideas.

“He comes across as a person with a lot of gravitas. I always think about the fact that he is a scholar, a teacher, an artist, and a musician–but also, he’s trained as a clown. He literally went to clown school. That tells you a lot about this side of my dad–he can be ridiculous.” She added that he created an interpretation of Breaking Bad from the viewpoint of a clown.

Dr. Miller describes to me how, growing up, Mr. Jackson would create paper dolls, working carousels, and masks for her. He would paint scenes on foam core for her My Little Pony toys. “All those things are still in the garage because he never throws anything away,” she laughed. Dr. Miller is grateful that her two daughters will have this same experience with their grandfather. She tells me she is “embarking on a project” to get Mr. Jackson to spend more time on the East Coast.

Dr. Miller recalls sitting down with her father at a blue iMac, combing through her high school papers sentence by sentence. Now, as Kassi’s collaborator, Mr. Jackson shares with her his knowledge of philosophy, which is very valuable to her research.

In the past few years, they have worked together to study the evolution of modern concepts of time. Jackson describes time as “science without causality” and “a bedrock principle that people believe in that they don’t even know they believe in.” He and Kassi focused their work on the way that time measured by the position of the sun evolved into technical thinking through the development of hours, minutes, and seconds.

Kassi Miller has her PhD in classics and is currently working on a project called Colby Justice Think Tank, which supports incarcerated scholars in independent research. She is a professor at Colby College, where she also conducts research. She attributes much of her interest in teaching and her pursuit of a graduate degree to her dad–the “consummate learner.” She tells me that he is often self taught. He even learned how to play the baroque flute and recorder on his own. “He modeled for me what it is to be a perennial and voracious student of everything,” she said.

She feels that part of his role as a teacher is to recognize his students’ individual needs and provide them with unique opportunities. To her, part of the beauty of his approach is the way that he gives his students exposure to his own passions and knowledge. He believes that even if a student is in 5th grade, they are capable of a higher level of understanding beyond the fundamental targets of the curriculum.

“There’s something holistic about creating things that draws on everything. The problem becomes to what extent you’re working within agreed upon rules. I would like to know what the rules of the game were in different periods, why stylistic choices were made. But also, I’m interested in people who decided to break the rules, and where that led,” said Mr. Jackson.

The rules say that the arts and sciences are separate disciplines. The rules say that things either are or they aren’t, that things are true or false. The rules say that education, democracy, and human identity must operate generically, without custom-fitting to the individual. Mr. Jackson’s magic as a teacher lies not in his answers, but in his questions and how they have shown countless kids and people how to open their minds and create.

José Ortiz • Jan 17, 2024 at 11:53 am

Both of my children had the blessing of his class at Coleman. He’s one of our all time favorites.

Kyan Baker • Dec 1, 2023 at 1:08 pm

Incredible profile of an incredible man.

Clive Baker • Dec 1, 2023 at 10:20 am

When I got put into the 4th/5th grade split I was worried I wouldn’t get Mr. Jackson, but he ended up switching to teach it. He is still the best teacher I’ve ever had.